10 Questions with Murphy Nile (Ziling Zhou)

Murphy Nile (Ziling Zhou) is a transmedia artist with an MA Degree in Computational Arts from Goldsmiths, University of London. His practice combines simulated 3D narrative environments with interactive audiovisual experiences, focusing on attention choreography and screen-based spatial dramaturgy. Through dystopian and absurd digital landscapes, he explores causal prediction, techno-fantasy, and historical reinterpretation, reflecting on the alienation embedded in technologically driven societies.

He was a Finalist for the Lumen Prize 2025 and was nominated for the UNESCO City of Media Arts Award at the IDIF Film Festival in Karlsruhe, Germany. His work has been exhibited and screened at venues and events including the Milan Machinima Festival (Milan), SUPERBOOTH 24 (Berlin), Galerie Met (Berlin), the Cadillac Shanghai Concert Hall, West Bund Museum (Shanghai), UFO Terminal (Shanghai), and Unreal Fest (Shanghai).

Murphy Nile (Ziling Zhou) - Portrait

Across Control Club, Cyber Matrix Prison, and Hum Doom, he treats digital systems not as neutral tools but as staged regimes, structures that choreograph attention, perception, and belief through rhythm, visibility, and constrained feedback. His work builds screen-based spatial dramaturgy: environments where the virtual and the real intertwine, and participation can feel voluntary while remaining structurally guided.

Control Club, Immersive Audio Visual Theatre, 2025 © Murphy Nile (Ziling Zhou)

Control Club is a loopable immersive audiovisual theatre work operated in real time with a game engine. Staged inside a circular LED matrix composed of two arcs, the piece choreographs orientation through visibility handovers rather than explicit choices: imagery repeatedly jumps between surfaces, cross-fading into blackout, or pulsing bright-on/bright-off rhythms, so viewers instinctively turn, relocate, approach, and search for detail, as if guided along an orbital path. High-velocity first-person traversals and dense particle atmospheres amplify the sensation of being inside a system that captures attention through tempo and reward. Audience presence is sensed and translated into subtle variations in flicker, density, and lighting, but the responsiveness is intentionally bounded: the environment reacts without yielding control, keeping the experience directional while still feeling alive. By shifting what can be seen, when, and where, Control Club studies soft control without commands, how timing and access to visibility can produce participation that feels voluntary yet remains structurally guided.

INTERVIEW

Let’s start with your background. You trained in Computational Arts at Goldsmiths. How did your studies there shape the way you think about digital systems and artistic authorship today?

My entry point into digital art began at 19, when I studied at Technoetic Arts Studio, founded by Roy Ascott. Technoetic Art introduced me to art and technology not as a collage of tools but as a way to think about connectivity, where data, telecommunication, interaction, wet media, and consciousness form one intertwined system. When I later entered Goldsmiths’ Computational Arts, I began treating digital systems as the site of authorship rather than a neutral toolbox. The question shifted from “what did I make” to “what conditions did I build,” including rules, rhythms, interfaces, and ways of seeing that shape how meaning happens. Goldsmiths’ critical environment and international network kept pushing me into a loop of making, testing, showing, and rethinking, where each project becomes a new experiment in how systems shape us in return.

Before arriving at your current transmedia practice, what earlier experiences or influences, either artistic, technical, or cultural, were most formative for you?

I’ve always been obsessed with digital media: hypertext, moving image, simulation, and the simple question of how computation can build a world. Being born around the millennium mattered. I grew up at a moment when the internet, software, and games were evolving quickly, and I spent a lot of time inside that ecosystem. Encountering Half-Life was a turning point. Its structure and atmosphere made me realise games could exceed “gameplay” and become a broader language for narrative and world-making, which sparked my interest in computer graphics and game engines. Installation and performance later became my way to step outside the screen to recover touch, presence, and the body, turning spectatorship into a physical relationship. At the core, my drive comes from two things: the narrative potential of media and a desire to explore what technology can do when it is still unknown.

Your works often treat digital technologies as “staged regimes” rather than neutral tools, as you mention in your statement. When did this perspective first emerge in your practice?

This perspective crystallised while making Control Club. I began with experiments in a circular matrix screen space and quickly realised the screen was not just a display. It behaved like an environment, almost a staged regime that tells your body where to turn, how to approach, and what to search for. That is when I started using screen switching, blackout, and pulsing brightness to turn viewing into a guided route. Audience movement modulates particles and lighting, but the variation stays within a logic of rhythm, reward, and “controlled chance.” In that moment, the engine stopped being a neutral renderer for me. It became a trained mechanism that reorganises participation, desire, and attention into something programmable.

Cyber Matrix Prison, Multi-Screen Installation, 2023 © Murphy Nile (Ziling Zhou)

Cyber Matrix Prison is an installation composed of five irregular screens forming a fractured, enclosure-like field of vision. At its centre, an AI-driven digital portrait continuously collapses and reconstitutes, shifting between cyborg textures and abstract metamorphosis through generative, real-time transformation, while the surrounding screens operate as a symbolic perimeter: high-saturation collage fragments, matrix-like glyphs, and signal-noise patterns circulate as if the environment itself is “computing” the subject. Rather than presenting identity as a stable face, the work treats it as a mutable output produced by an image system: assembled, dissolved, and re-rendered under a persistent pressure to update. The spectator’s position, always partly inside, partly outside the portrait’s field, mirrors the work’s premise: in a networked visual regime, subjectivity is not simply represented; it is processed, and the prison is not a cage of metal but a loop of images that never fully resolves.

Can you walk us through your creative process, from the initial concept to the construction of a simulated environment or installation?

My projects usually start from intuition, sometimes a sudden image, sometimes a social situation that irritates me, or a feeling that something is quietly wrong. I begin by drafting a world and its operating rules, not a full script but a protocol: who is allowed to act and what triggers reward, punishment, or silence. Then I move quickly into technical prototyping, using Unreal, real-time visuals, and sound, so the idea can stand up as a working system. Through trial and error, I calibrate rhythm, gaze direction, and interaction thresholds until the audience’s bodily response becomes almost predictable. I call this kind of orchestration attention choreography. The final step is stepping back from technology and returning to the narrative core, removing anything that is just spectacle and keeping only what truly serves perception and meaning.

You work with game engines, AI systems, real-time data, and sound. How do you choose the medium and tools for each project, and how hands-on is your relationship with the technology itself?

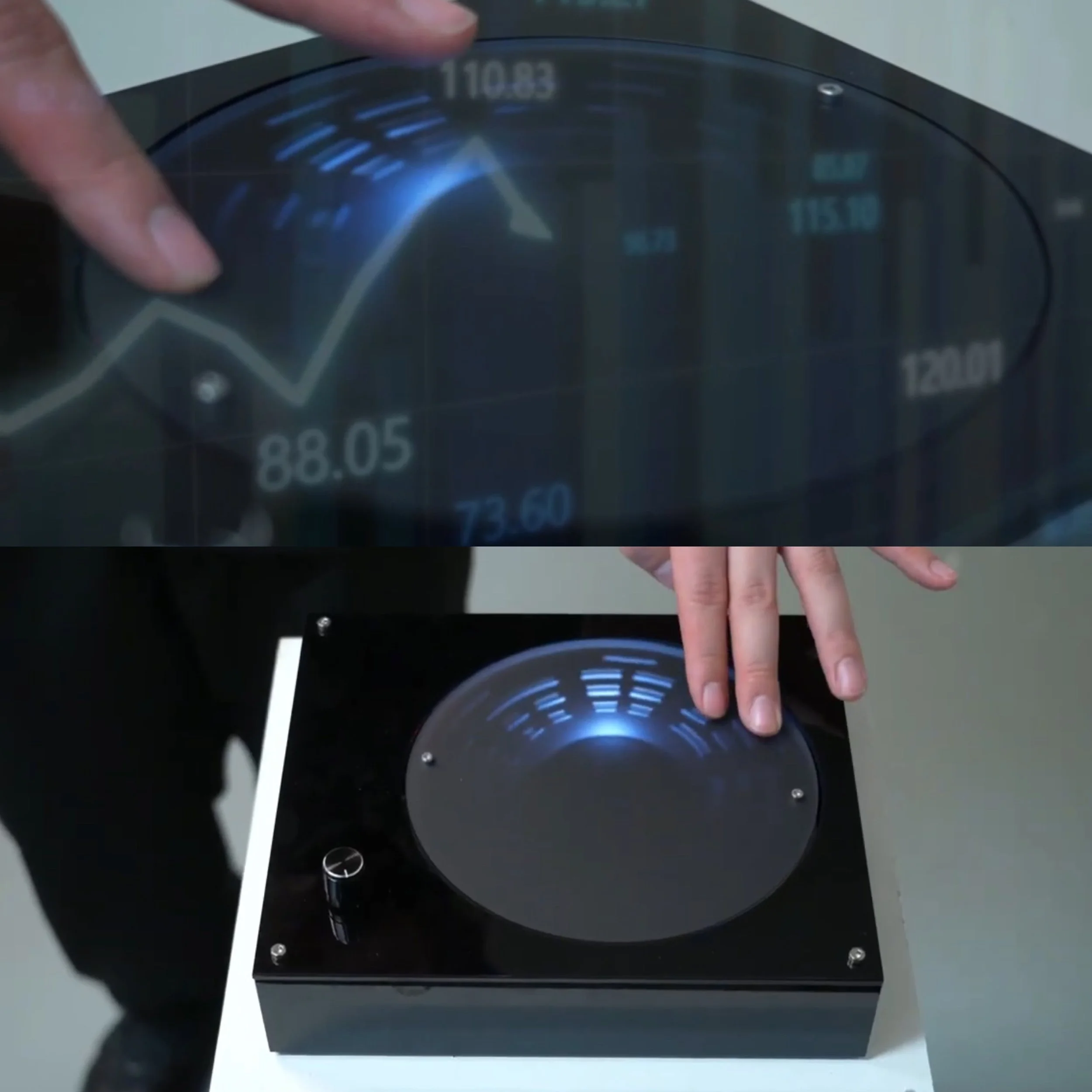

My rule is straightforward: technology must serve the story, and specifically, the feeling the audience needs to experience. So I choose tools by asking whether the work should make you feel pulled, trapped, seduced, or quietly managed. If I need a world that can “run” like a governance system, I use a game engine. If the work needs identity to remain unstable and continuously transforming, I bring in AI generation. If the system should feel alive, breathing with volatility, I use real-time data and sound. In Hum Doom, for example, Feng Shui metaphors and live stock market dynamics become a sonic field the body can intervene in. Slow, Tai Chi-style movement disrupts the soundscape, like interrupting a ritual of algorithmic prediction. And yes, I’m very hands-on. I prototype, build the logic, tune parameters, and push the system until it behaves like an environment, not a demo.

Hum Doom, Real-time interactive sound installation, 2024 © Murphy Nile (Ziling Zhou)

In projects like Control Club and Cyber Matrix Prison, the audience’s agency feels present but limited. What interests you about this tension between participation and control?

I’m fascinated by the feeling that agency is present but difficult to fully break through because it mirrors everyday life. We think we’re choosing freely, yet the boundaries are often written in advance by interfaces, rules, and timing. In Control Club, audience movement does modulate visuals and light, but the overall experience still behaves like an engineered orbit. Reward structures keep you moving, and the more engaged you become, the harder it is to step out. For me, this isn’t anti-interaction. It’s a more honest kind of interaction. It makes the boundary tangible and triggers a desire to push against it. In a way, I use engagement as an entry point. The work truly begins when you realise you are being guided.

Dystopia, absurdity, and techno-fantasy recur across your work. Are these themes rooted more in contemporary realities, speculative thinking, or personal experience?

For me, dystopia, absurdity, and techno-fantasy are a private way of seeing the world, but they’re never detached from reality. The core comes from lived experience, social attention, intervention, and critique. I often find myself positioned between different cultural, economic, and political systems, and I keep switching roles, subject, object, and strategy to search for a “middle state” that neither fully takes sides nor fully escapes. The absurdity often emerges from that gap. When systems become extremely precise, yet human emotion and fate are reduced to variables, reality already starts to feel like science fiction. That in-between condition holds the strongest tension for me. It lets me push the real world slightly overexposed, so audiences can suddenly perceive structure in the space between laughter and unease.

Your work has been shown in a wide range of contexts, from festivals to galleries and concert halls. How does the setting influence how audiences engage with your installations?

I adapt the work’s entry strategy depending on the setting. In festivals or screening contexts, attention time is shorter, so I make narrative cues clearer and pacing tighter, so you should be hooked within minutes. In galleries, I care more about multiple entrances and rewatchability. You can enter the system from anywhere and slowly discover its rules and traps. In concert halls or live performance contexts, the work becomes an event. I treat visuals as a parallel bodily pressure to sound, moving with musical energy and directly affecting breathing and attention. With multi-screen installations like Cyber Matrix Prison, scale and screen arrangement reshape the logic. You’re not viewing a single image; you’re forced to rebuild “identity” across fragments. And with Control Club, the circular matrix architecture turns audience movement into the piece itself. The more immersive the site, the stronger the sense of governance.

Hum Doom, Real-time interactive sound installation, 2024 © Murphy Nile (Ziling Zhou)

Hum Doom translates invisible systemic forces into an evolving sonic ritual by linking Feng Shui / Bagua logic with real-time stock market data. The work generates a live synthesiser soundscape in which market fluctuations are mapped into audible parameters, density, pitch drift, pulse rate, spectral brightness, and spatial movement, so that finance becomes felt as pressure, vibration, and atmosphere rather than numbers on a chart. Bagua functions not as decoration but as an organising interface: it frames how data is partitioned, routed, and interpreted, placing ancient spatial reasoning beside algorithmic measurement. The audience is invited to intervene through slow circular gestures, interrupting and recomposing the sound field, as if attempting to “stabilise” chaos, yet the system inevitably reasserts its own momentum. Hum Doom asks what kind of power we are hearing when prediction becomes performance, and when volatility, historical trauma and present speculation return as a continuous hum that surrounds the body.

How have critics, curators, or audiences responded to the idea of “attention choreography” and screen-based spatial dramaturgy in your work so far?

One of the most precise responses I’ve received came from curator Sen Send when Control Club was shown at UFO Terminal in Shanghai. She described the engine not as an image tool but as a managerial structure. It absorbs audience movement and feedback, turns “engagement” into a form of precise guidance, and uses rhythm, visual impact, and reward to lock bodies and gaze into predetermined paths. What struck me most was her point that, within such smooth and airtight logic, the exit toward autonomy is exactly what’s missing. For me, that captures the core of my practice: staging control as something that doesn’t feel like control, turning governance into atmosphere, and attention into spatial dramaturgy.

Lastly, looking ahead, are there new technologies, formats, or conceptual directions you are interested in exploring in your future projects?

I’ll always stay curious about new technologies. That curiosity is part of my creative fuel. But I also approach technological acceleration with caution because “new” often introduces new power structures and new blind spots. I’m not interested in using tech just to look cutting-edge. I want to use it to respond to what’s happening inside a technological society: how algorithms shape desire, how prediction replaces debate, and how interfaces become new moral orders. Formally, I want to keep expanding the relationship between screens, bodies, and space. That includes more complex multi-screen dramaturgies, stronger real-time behaviour, and participation structures that feel open while still making their boundaries perceptible. I like my practice to remain in evolution. After finishing one work, I let it go completely and enter the next experiment with a fresh question.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a curated promotional platform that offers artists the opportunity to articulate their vision and engage with our diverse international readership through insightful, published dialogues. Conducted by Mohamed Benhadj, founder and curator of Al-Tiba9, these interviews spotlight the artists’ creative journeys and introduce their work to the global contemporary art scene.

Through our extensive network of museums, galleries, art professionals, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide, Al-Tiba9 Interviews provides a meaningful stage for artists to expand their reach and strengthen their presence in the international art discourse.