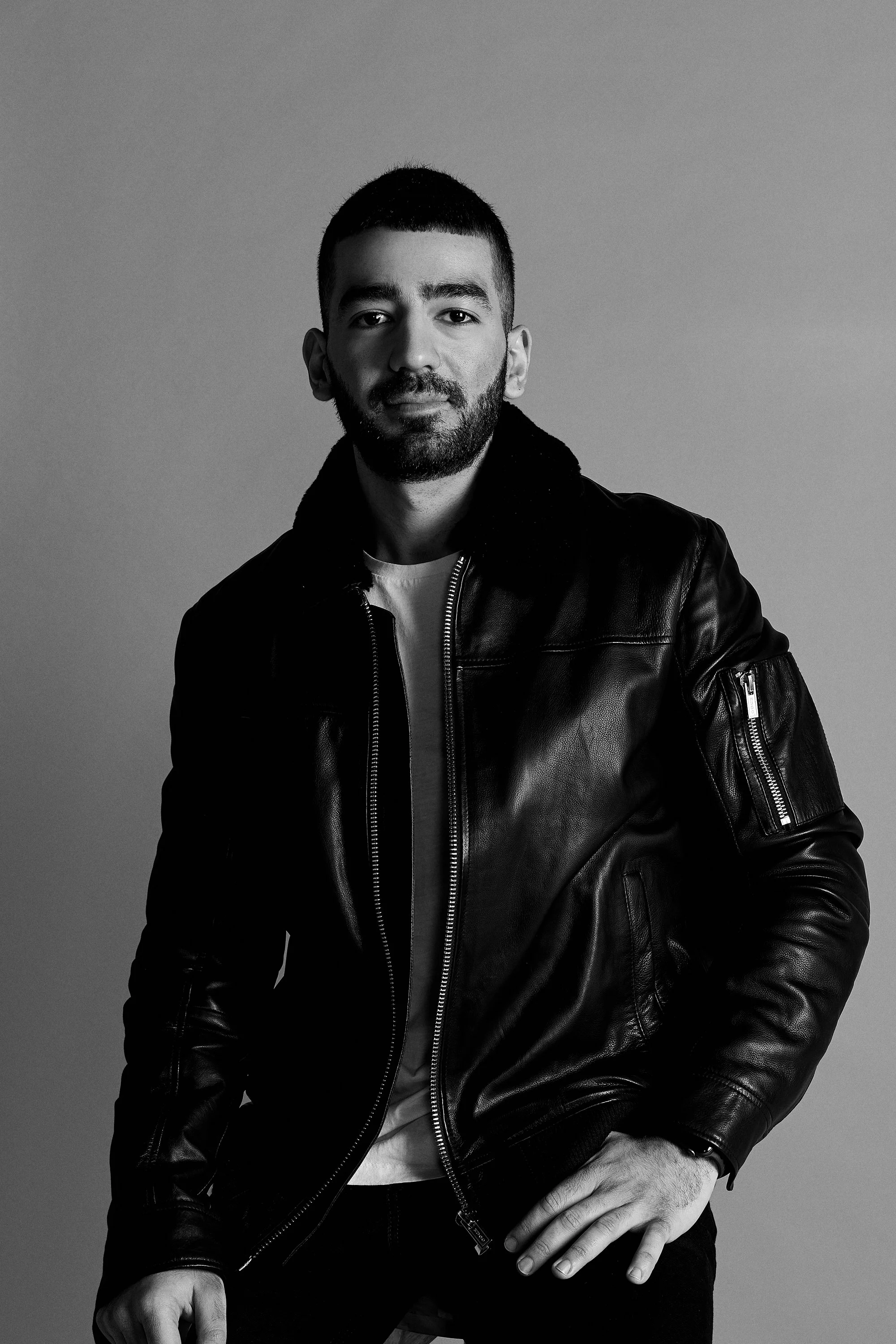

10 Questions with Ashraf Malek

Ashraf Malek is a contemporary multidisciplinary artist shaped by a foundation in architecture and an evolving international trajectory. His early training instilled a deep engagement with spatial systems, structural logic, and the cultural forces embedded within the built environment. Seeking to move beyond conventional design-led methodologies, Ashraf transitioned toward an expanded artistic practice. He now prioritises conceptual inquiry and experimentation. A pivotal moment in his development occurred after relocating to Vancouver, Canada. His work at the Vancouver Art Gallery provided sustained exposure to contemporary art discourse, institutional practice, and curatorial frameworks. This experience informed his shift toward working across digital projections, painting, 3D modelling, moving image, coding, and filmography. His work has since been presented at major cultural platforms. These include the 2023 Coronation Concert of King Charles III, Tate Modern, Aures Gallery in Waterloo, Gorvy Theatre, and Genesis Cinema in East London. In 2024, the Royal College of Art selected his work for a commemorative tote. The tote celebrates the institution’s decade-long recognition as the world’s leading art and design university. Ashraf is currently working with CW Plus on the RELAX Digital programme. He is creating moving-image artworks for hospital environments. These are presented on digital screens in waiting and treatment areas, extending his practice into patient-centred therapeutic contexts that integrate art, care, and technology.

Ashraf Malek - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Ashraf Malek is a contemporary multidisciplinary artist whose practice investigates space as a fluid, destabilised construct shaped by perception, memory, belief, and ideology. Grounded in architectural thinking yet not bound by its formal constraints, Malek’s work gradually shifted from the order and logic of architecture to an exploratory language that treats space as unstable, speculative, and psychologically charged. He dismantles dominant spatial hierarchies through the study of hyperobjects, meta-localities, and fragmented destinations, interstitial states generated by the unconscious and activated through memory, belief, and perception. Employing digital distortion, glitches, and spatial deformation as generative tools, he uses disruption as a method of cognitive inquiry, not as error. Malek interrogates the avatar as an abstract extension of self and examines how faith, conviction, and ideological systems become spatially embedded within contemporary life. His critical engagement with artificial intelligence and emerging technologies considers their social and mental implications on perception and agency. Through multidisciplinary methods, digital projections, painting, moving image, 3D modelling, coding, and filmography, he constructs speculative environments that challenge fixed notions of presence, authorship, and spatial continuity, inviting viewers to reconsider how space is dismantled, reassembled, and inhabited in an era of technological acceleration.

Malek’s early development within architecture nurtured a sensitivity to spatial systems and ideological forces in the built environment. His practice has since moved away from architecture’s problem-solving imperatives, evolving into a multidisciplinary exploration of space as fragmented, unstable, and speculative. This transition represents a gradual repositioning of architectural thinking toward more uncertain and perceptual forms of inquiry.

A decisive turning point came through his experience at the Vancouver Art Gallery, where exposure to institutional practice and curatorial discourse complicated his relationship to space and authorship. This broadened the scope of his practice, which now spans digital projections, painting, moving image, 3D modelling, coding, and filmography. These media are used as provisional tools to articulate spatial fragmentation and mental projection, enabling his work to circulate across contexts from experimental screenings at Genesis Cinema in East London to the 2023 Coronation Concert of King Charles III.

Architectural logic remains present in Malek’s work but is consistently unsettled through digital distortion, glitches, and spatial deformation. These disruptions serve as reflective mechanisms, questioning rather than resolving space. His environments often occupy the territory between physical and psychological realms, meta-localities or fragmented destinations activated by the unconscious and mediated by ideology. This approach has resonated in institutional contexts, with exhibitions at venues such as Tate Modern and Aures Gallery in Waterloo, where his resistance to fixed spatial narratives becomes especially pronounced.

The recurring figure of the avatar in Malek’s work functions as an abstract extension of self, quietly testing issues of authorship, embodiment, and agency. Faith and conviction are examined not as personal beliefs but as spatial forces shaping contemporary experience. Malek’s engagement with artificial intelligence and technology remains cautious and analytical, viewing technology as a psychological agent that subtly reshapes perception and space. This tension was highlighted in 2024, when the Royal College of Art selected his work for a commemorative tote, situating his practice within institutional reflection.

What distinguishes Malek’s work is its refusal to offer stable conclusions. His environments remain unresolved, suspended between coherence and disintegration, presence and absence. Instead of seeking clarity, Malek invites contemplation, prompting viewers to consider how space is constructed, inhabited, and believed in an era of technological mediation. His practice remains committed to inquiry and sustained questioning, evolving through ambiguity rather than synthesis.

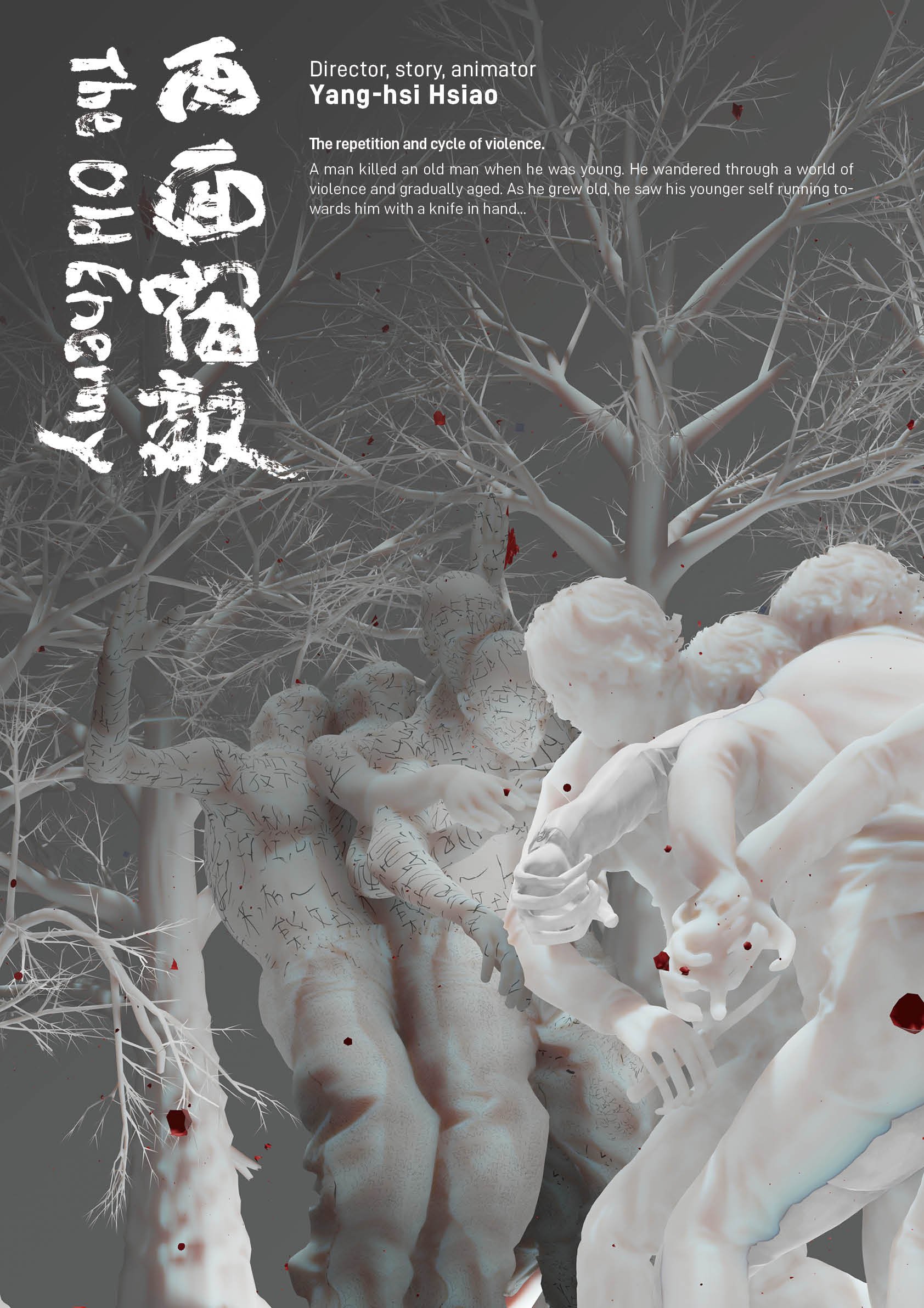

Viscous Horizon, Moving Image, Cinema, 2023 © Ashraf Malek

INTERVIEW

Let’s start from the basics. Your background is in architecture. What first pushed you to move beyond traditional architectural practice into art?

My background in architecture really comes from a long fascination with space, and with how we move through it and experience it. I was always very invested in architecture, and I still am, but I kept finding myself pulled toward its more conceptual and experiential sides. Even when I was studying architecture, I would linger in the early stages of a project, thinking less about how something should function and more about what space was doing- how it was being felt and what it meant. That open, speculative moment was always the most compelling to me. I was drawn less to formal resolution and more to abstraction, to questions of dimension and perception, and to the quieter ways space shapes us without us always realizing it. Over time, architecture became the ground I was working from rather than the destination itself. It gave me a rigorous way of thinking about space, but my artistic practice allowed me to loosen that structure, to pull ideas apart and reassemble them differently. Through art, whether in digital media, live performance, or installation, I’ve been able to stay with those questions more freely. That space for speculation, for uncertainty, for challenging definitions, is really what continues to drive my work.

Don’t Touch Me, Digital Screen, Projection, 2023 © Ashraf Malek

How did relocating to Vancouver influence the way you make art?

Relocating to Vancouver shifted something fundamental in how I began to think about the relationship between art and the natural environment, though I did not recognise it immediately. Being there, working early on at the Vancouver Art Gallery, offered a kind of practical education. It gave me firsthand insight into how art operates within institutional frameworks, how work is positioned, interpreted, and strategically presented within public and exhibition contexts. The Gallery itself, situated at the centre of the downtown core, carries a particular weight, and navigating its freedoms and constraints became an informal site of learning for me. I began to understand more clearly how audiences engage with art and how institutions shape those encounters, sometimes subtly, sometimes very directly.

Outside of that context, Vancouver’s landscape was equally formative. The natural environment became a constant source of inspiration, but also a place of thinking and making. The outdoors functioned as a kind of studio, where ideas could be generated through movement, observation, and time spent in nature. Many sketches and concepts developed in those settings continued to resurface and inform my practice years later. Alongside this, working in design management within the private sector introduced another layer to my understanding of space. It expanded how I thought about interior environments and professional collaboration with artists. Taken together, the city’s cultural diversity and spatial complexity offered a dynamic context in which ideas could be tested, challenged, and reshaped in relation to audience response and lived experiences.

You work across many media, from painting to coding and moving images. How do you decide which medium a project needs?

For me, choosing a medium is never a fixed decision. It tends to emerge slowly, through an ongoing process of experimentation, and that way of working comes directly from my background in architecture. Sketching, modelling, testing ideas, none of it ever felt like a linear path, more like a continuous loop of inquiry. I carried that with me into my artistic practice. The work begins to unfold through different modes of expression, sometimes digital, sometimes physical, sometimes performative, and often overlapping without a clear hierarchy. Context matters a great deal. Where the work will live and how it will be encountered begins to shape the medium rather than the other way around. I tend to think of space as a philosophical site, something activated through use, perception, and layering. When multiple media are brought into relation with a space, a dialogue starts to form, not just between materials, but between experience and meaning. This is not about preference or style for me; it is about finding the medium that can most clearly carry an idea to the audience. I understand the medium as a critical tool of expression, one that remains flexible, and contemporary digital platforms have only expanded that field, opening up new ways for digital and physical forms of expression.

Until The Path Becomes, Digital Projection, Windsor Castle, 2023 © Ashraf Malek

Space is central to your work. What does “space” mean to you outside of architecture?

For me, space has never functioned as a neutral dimension or a purely physical container. I keep returning to it as a phenomenological construct, something shaped by perception, embodiment, and lived experience rather than by form alone. It is not simply what exists outside the body. It is assembled through the human sensorium, through mechatronic interactions, acoustic resonances, and visual stimuli that seep into emotion and begin to create meaning. I think about space as something that operates simultaneously outward and inward. It may appear as a collective environment, expansive and shared, yet it is just as much an interior site of confrontation, intimate and personal. That tension, the external gaze folding back onto the self, continues to drive my thinking around the environment. Even when my work occupies large physical spaces, scale is not the point. What matters is how those spaces are experienced individually, often quietly. In this way, space in my practice becomes less about dimension and more about an internal, ongoing yearning, one that is personal, experiential, and never fully resolved.

You often use distortion and glitches. What attracts you to disruption as a creative tool?

When we think about space, there is often an impulse to build, to impose order, to add and refine. I have found myself moving in the opposite direction. My practice is rooted more in deduction, in removing, disrupting, and allowing the unseen to surface. Distortion and glitches have become tools of philosophical inquiry for me, not as effects, but as ways of interrupting expectation. By breaking the flow, whether through painterly distortion or pixelated interruption, something opens up. The familiar begins to slip. These moments of disruption create pauses, points of uncertainty, where questions can emerge rather than answers. Within that instability, I am interested in what might be revealed. A kind of raw consciousness beneath accumulated layers. The tension between signal and noise, between reality and illusion, becomes more visible. In this sense, disruption becomes a method. It allows for the interrogation of authenticity itself, for asking what exists beyond surface readings and beyond conventional understandings of space. I often think about glitches in music, how they can reshape tempo or produce new forms of listening. In a similar way, glitches in space can generate awareness. They interrupt continuity, and in doing so, they create openings where perception shifts and more personal forms of truth can briefly come into focus.

Your work explores the idea of the avatar as an extension of the self. How do you personally relate to this concept?

The idea of the avatar in my work didn’t arrive as a clear concept; it sort of started while I was thinking about how the self shows up once we enter immersive virtual worlds. I wasn’t interested in the technology itself so much as what happens to identity inside those spaces. It’s not about looking through a screen or stepping into a digital environment. I keep coming back to the avatar as something closer to a reflection, or maybe a misalignment- an extension of the self that is never quite stable. Control feels strange there. You can move freely, make choices, navigate space, but everything is still experienced through a personal lens that carries memory, bias, and projection. In my artwork ‘Somewhere to Belong’, for example, I worked with the figure of Adonis as a digital manifestation within a live performance that was constantly shifting in response to live music. The avatar wasn’t fixed - it was forming itself in real time. That’s where it became interesting for me, as a kind of bridge between my physical presence and the digital space it was inhabiting. In a way, that work mirrors how I approach these environments myself, moving through them while questioning where identity sits, how it is constructed, and how easily it can be unsettled once everything becomes immersive and fluid.

Viscous Horizon, Moving Image, Cinema, 2023 © Ashraf Malek

Viscous Horizon, Moving Image, Cinema, 2023 © Ashraf Malek

Technology and AI play an important role in your practice. What questions do they raise for you as an artist today?

The questions that emerge in my practice around AI and technology stem from the constant use of social media and digital tools that now permeate our daily lives. Issues around privacy, transparency, and autonomy surface in different ways, often when I’m thinking about how easily we move through digital platforms without fully noticing what is happening beneath the surface. Our ideas of intelligence quietly shape perception, and that recalibration often goes unregistered. There is a speed and acceleration to all of this, but I find myself continually returning to the human experience. Emotional registers, embodied moments, and uncertainty still feel essential. My practice tends to settle in that space where human presence introduces friction and affect into technologically mediated environments. As systems of intelligence become more embedded in everyday structures, my thinking has shifted. It no longer feels sufficient to talk only about knowledge or information. Questions of consciousness, agency, and embodiment begin to take precedence. What allows human agency to persist now feels less obvious, more introspective, and perhaps more fragile. I am not convinced these questions resolve themselves; they require continuous experimentation and testing. While there is understandable anxiety around domination, replacement, and control, I am less interested in opposition than in coexistence. Through art, immersive environments, and projection, I continue to imagine a middle ground, one that remains provisional and unresolved, where different forms of intelligence can exist side by side and where belonging is something continually negotiated rather than fixed.

The RELAX Digital programme brings your work into hospital environments. How did working in a therapeutic context change your approach?

Working on the Relax digital programme with CW+ felt like a continuation of a line of thinking in my practice that began much earlier, during my time in Vancouver, where nature first became a central influence in how I approached art. Entering a hospital context shifted that thinking in a significant way. It brought with it a heightened sense of responsibility, and with that, the need to understand patient therapy and the very different ways people encounter art when they are in vulnerable or high-pressure situations, including emergency environments. That experience stayed with me. It reshaped how I think about the urgency of the arts and their potential role in healing and care. I began to consider art not only as a space for contemplation or reflection, but as something more active, something that could genuinely offer calm or relief. In developing this project, I paid close attention to the architecture of the new hospital spaces, looking for ways to bring aspects of the outdoors inside. This felt like a return to earlier concerns in my practice, particularly my interest in nature as a grounding force for the human body. Working in this context made those ideas feel less abstract and more immediate. This project marked an important moment for me. It demonstrated how art within therapeutic settings can shift from being purely inspirational to having a direct and meaningful impact, and it continues to influence how I think about audience, care, and responsibility within my work.

Viscous Horizon, Moving Image, Cinema, 2023 © Ashraf Malek

Viscous Horizon, Moving Image, Cinema, 2023 © Ashraf Malek

Your projects have been shown in very different settings, from museums to public events. How do audiences influence your work, if at all?

For me, the audience has always felt central to the work, perhaps more than anything else. Without emotional resonance, a piece can feel fixed, almost inert, as if it has closed in on itself. That is often when I return to live performance. There is something about being in the same space, at the same time, that changes the conditions entirely. Control begins to slip, and time behaves differently. When I am physically inside a performance and responding to what is unfolding in the room, the work starts to move in ways I cannot fully anticipate. Sometimes the exchange is fluid, sometimes awkward or unstable, and I have come to value that instability. It keeps the work alive. I do not think of audiences as passive observers. Their presence alone alters the atmosphere before anything else happens. A reaction, a pause, a shift in attention, even a small movement can redirect the work entirely. As technologies increasingly allow for real-time input, participation, and data exchange, this relationship becomes more open and porous. Authorship begins to blur. What continues to hold my attention are those moments when the work feels collectively held, when agency is shared rather than fixed. These exchanges shape how I think about performance, about participation, and about presence itself, and they sit at the core of how my practice continues to evolve, raising questions that I remain invested in working through.

Lastly, what are you currently curious about, and how do you see your practice evolving in the near future?

I see my practice moving toward larger-scale digital experiences, not simply as a formal shift, but as a way of thinking through questions of consciousness, presence, and how space is understood across physical and virtual conditions. The human experience remains at the centre of this work. Still, I find myself increasingly drawn to what happens when participation becomes collective, when perception begins to shift, and a shared awareness starts to form. Over time, my practice has moved away from moving image and toward live responsive systems. Interaction no longer feels secondary; it becomes part of the work itself. Within these environments, I continue to explore embodiment, agency, and the role of the avatar, particularly as immersive spaces open up multiple points of reception, response, and data exchange. Technology supports these inquiries, operating as a set of tools rather than a driving force, and allowing projection and interactive structures to exist at a scale that invites communal engagement.

At the same time, I remain committed to more traditional forms of experimentation. Painting, in particular, continues to function as a tool for conceptual development and visual thinking. These approaches exist alongside one another. Increasingly, though, I am drawn to expansive, collective projections and immersive environments. This is where the philosophical and experiential direction of my practice currently feels most alive.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.