10 Questions with Yang-hsi Hsiao

Yang-hsi Hsiao is a visual creative practitioner and XR researcher working at the intersection of design, psychology, social issues, and immersive technology. Growing up in poverty and instability, her educational path was slower but steady, shaped by an early life rooted in “having nothing.” Over time, this fearlessness toward loss transformed into a sense of openness and freedom that continues to inform her creative practice.

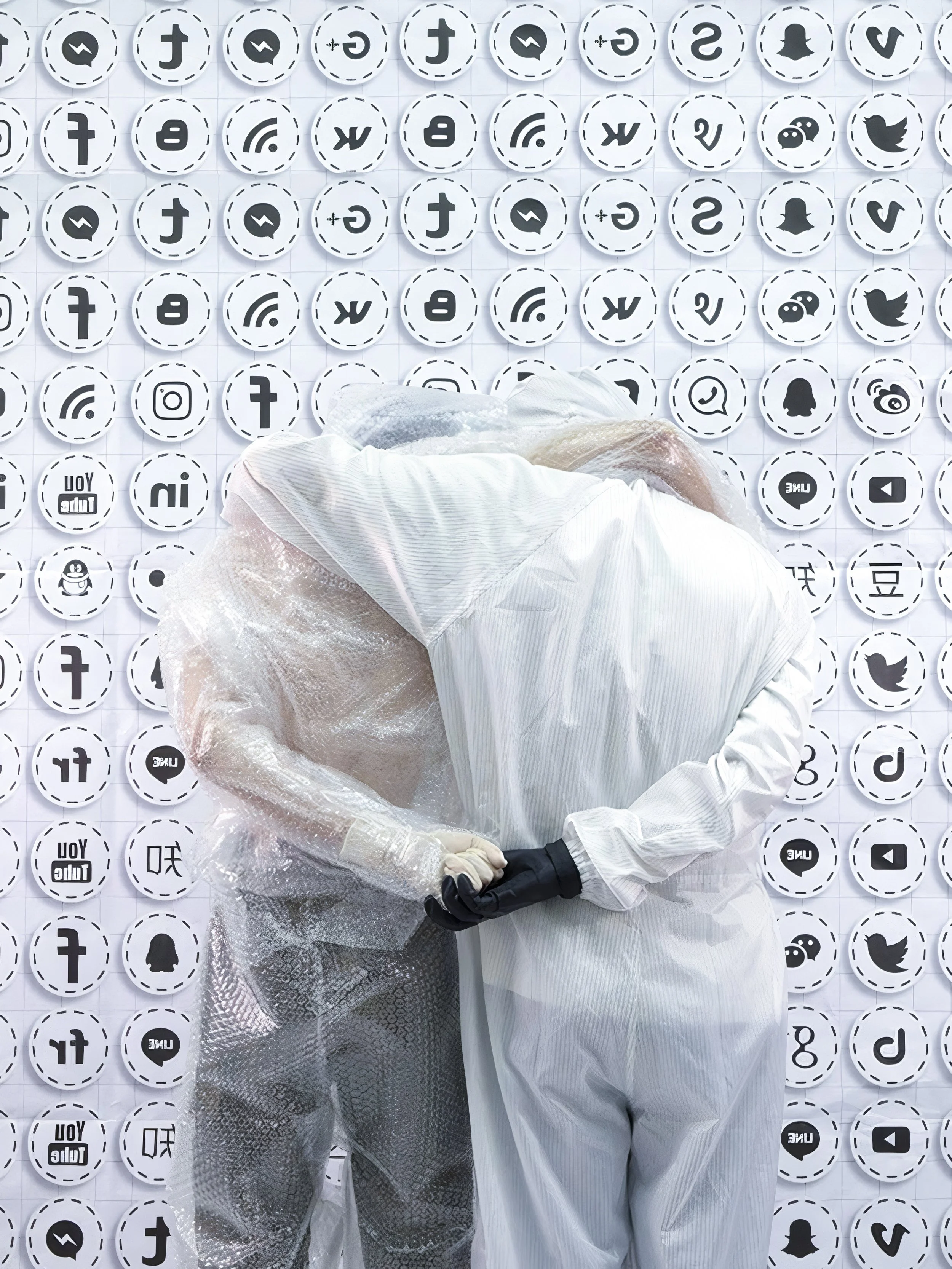

Through work across cultural arts, social movements, and commercial design, she became increasingly aware of how digital environments extend, disturb, and transform emotion and perception. This led her to immersive media research and to pursue an MA in Virtual Reality at the University of the Arts London. Her research focuses on the psychological dimensions of immersive experience.

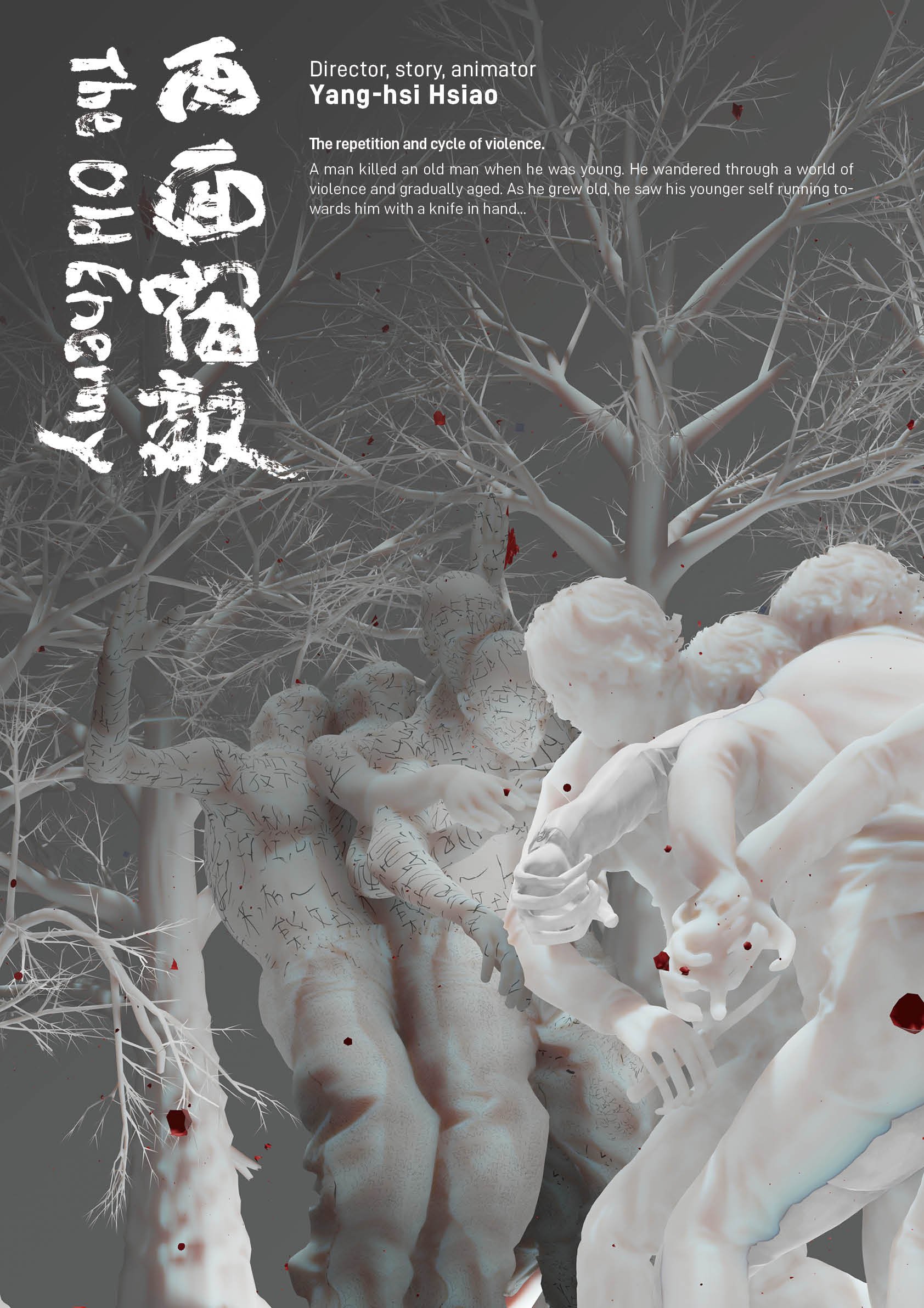

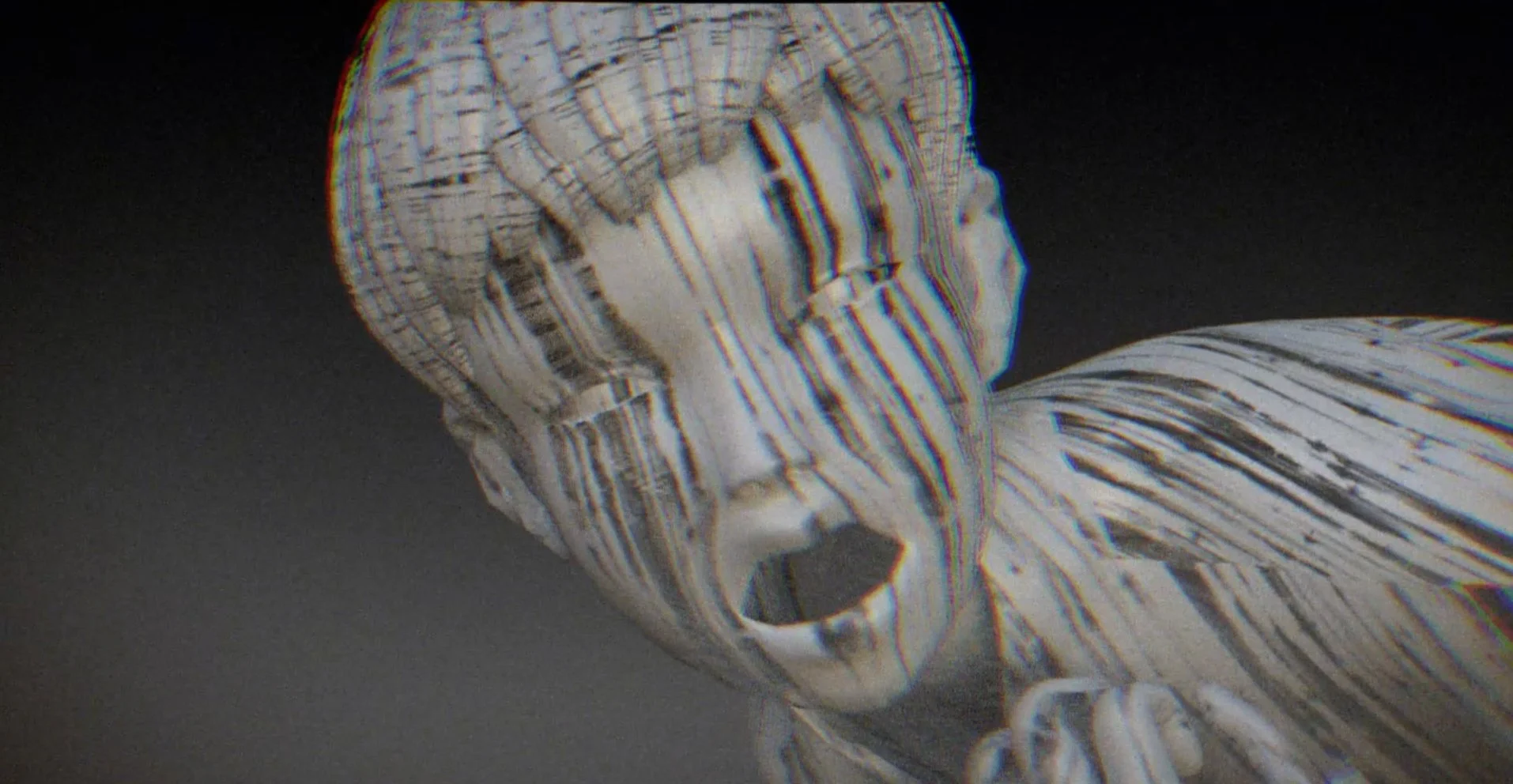

Her recent work, The Old Enemy, reinterprets an oral history from an earlier project, Da Yin Wang Shan, created for her hometown in Taiwan. Based on a real story about her grandfather’s friend, who committed multiple murders and later lived hidden in the mountains while peacefully coexisting with her family for years, the work examines cycles of violence and how trauma circulates among victims, perpetrators, and bystanders. Using low- and high-frequency sound to evoke embodied states of numbness and freeze responses, combined with 360° visual rhythm, the work reshapes emotional tension and subjective time.

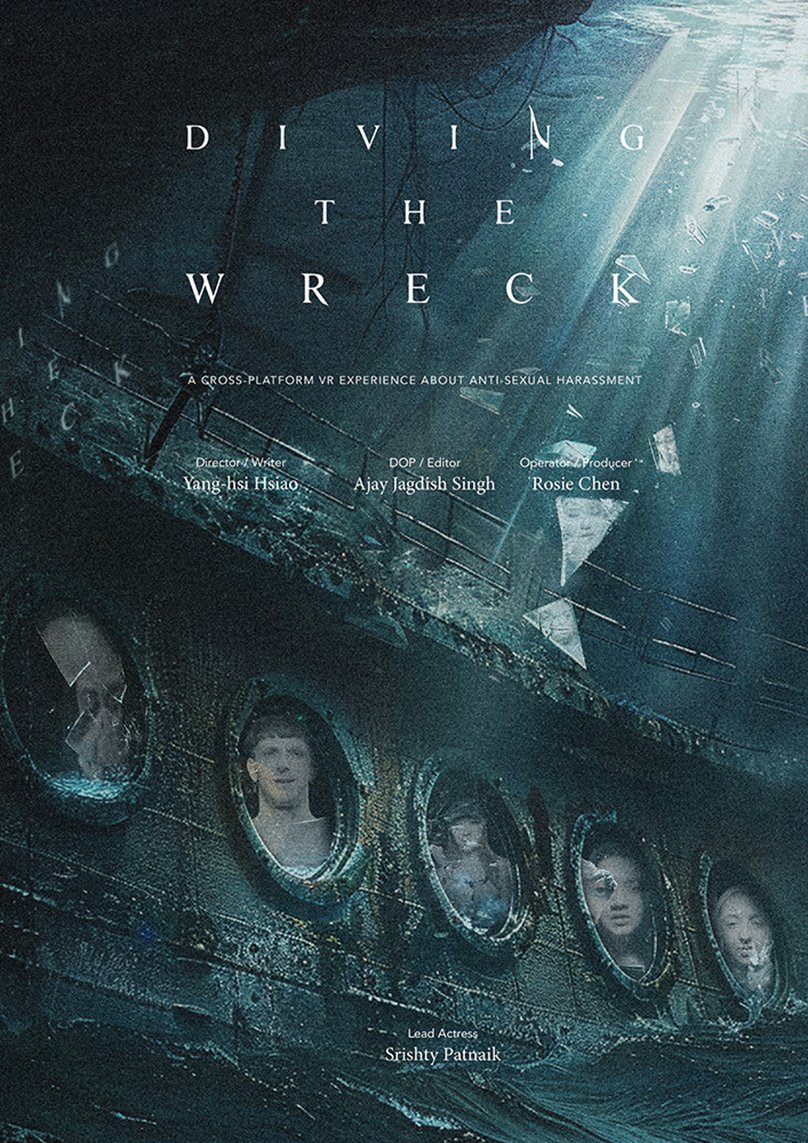

Another project, Diving Into the Wreck, integrates behavioural psychology and sexual-harassment prevention, examining how immersive environments influence subtle human actions. Focusing on bystanders who hesitate to intervene due to perceived vulnerability, the project proposes safe and accessible intervention strategies, challenging the assumption that only the strong or confident can act. Through immersive design, her work connects trauma research with social inquiry, offering new frameworks for understanding vulnerability, agency, and emotional regulation within XR practice.

Yang-hsi Hsiao - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Yang-hsi Hsiao’s work is rooted in the question of existence. Growing up in an environment where disappearance, both literal and emotional, was a recurring reality, she became attuned to the fragile edges between presence and erasure. The mountains of her rural upbringing shaped her worldview: they hold all things without judgment. Whether predator or prey, fragile or fierce, everything finds a way to coexist. This philosophy grounds her artistic practice.

She uses immersive media to graft new forms of perception onto the body. By amplifying sound frequencies, spatial rhythm, and subtle sensory cues, she explores how people encounter fear, tenderness, trauma, and acceptance. Her practice asks how we might become like a mountain, capable of holding all parts of experience, even those we were taught to deny. Drawing from spatial design, experimental sound, and behavioral psychology, she creates environments that invite viewers to inhabit states they often avoid in daily life.

The significance of her work lies in its attention to overlooked, vulnerable realities. Focusing on questions small in scale but immense in impact, she brings these fragile spaces into immersive form, offering new ways of sensing, remembering, and accepting what exists.

The Old Enemy, VR, 2025 © Yang-hsi Hsiao

INTERVIEW

Growing up with experiences of poverty and instability clearly shaped your worldview. How has this early sense of “having nothing” influenced the way you approach risk, loss, and openness in your artistic practice?

The idea of “poverty” didn’t really take shape for me until secondary school. As a child, we rarely had snacks. My mother would dig up cinnamon roots from the soil and give them to us as treats, and even now I remember that taste as something genuinely good. My “toys” were always trees and rivers, and I never owned the kinds of things that are widely considered “cool”. I only learnt much later that poverty can carry shame. As for instability, it felt less like an exception and more like something naturally woven into everyday life.

Those experiences shaped a pragmatic approach to risk in my practice. What I call boldness isn’t reckless. It rests on assessing risk, taking responsibility for it, and breaking it down into steps you can actually move through. Because of that, I’m less inclined to panic in the face of loss. Loss can bring a temporary collapse on the surface, but it doesn’t destroy the core.

At the same time, “having nothing” gave me a strange kind of openness. I stay curious about the unknown, including my own mind and body. That openness is also what allowed me to move from visual design into XR research, and to hold uncertainty rather than resist it. When I think of life as a spectrum from zero to infinity, something I can move along freely, I’m less likely to become overly self-satisfied by what I gain, and less likely to be overwhelmed by fear when I fail.

The Old Enemy, VR, 2025 © Yang-hsi Hsiao

Your work sits at the intersection of design, psychology, social issues, and immersive technology. How do these disciplines inform each other when you begin developing a new project?

I see these four fields as different coordinates within a single practice. Design shapes my aesthetics and narrative, giving the work its tone, rhythm, and the viewer’s pathway. Psychology and social issues provide analytical tools that allow me to push questions into deeper, more difficult territory. I’m not simply expressing emotion, but trying to understand how it is formed and how it travels between people.

Immersive technology is the medium through which these questions can be experienced. What I investigate is how, in XR, instinct and bodily responses can be activated, so the audience doesn’t only “understand,” but encounters the work through sensation and position.

When developing a new project, I usually begin with a question that genuinely unsettles or puzzles me. I then keep recalibrating across these four fields, and finally return the freedom of interpretation to each viewer, allowing them to decide where it ultimately lands. Whenever I see different responses, I find it deeply compelling, because it lets me see more clearly how rich and multi-dimensional human experience can be.

What first drew you to immersive media and XR as your primary tools, rather than more traditional visual or narrative formats?

What first drew me in was the way immersive media can enfold the user. Their position, distance, direction, sound, point of view, and even their breathing rhythm can become part of the narrative. Over time, I became increasingly interested in how immersion can amplify perception. For example, viewing the Earth “from space” in VR can evoke something akin to the overview effect, bringing a loosening, a calm, and a shift in scale that is felt rather than simply understood. In research and therapeutic contexts, VR has also been used to work with fear responses through graded exposure and desensitisation. My interest here is not in making any promise of cure, but in what this demonstrates: immersive experience is not only an aesthetic form; it can also be designed to shape attention, bodily activation, and embodied meaning across different fields.

I’ve also always found less-defined, still-unfinished media more compelling, and immersive media feels like a language that is still forming. It doesn’t yet have a fixed grammar, which gives me room to “invent” it in my own way. For me, it’s not simply a change of tools, but a shift towards meaning-making that is co-produced by the work and the viewer.

In The Old Enemy, you reinterpret a deeply personal oral history connected to violence and coexistence. How did you navigate the ethical and emotional complexity of translating this story into an immersive experience?

When translating this oral history into VR, I was careful to ensure that “understanding” would not be misread as “justification”. The work has been criticised as though it were speaking on behalf of the perpetrator, but I chose to face that tension directly. If we remain only at the level of moral condemnation, violence often returns in other forms. A deeper kind of understanding, however, may allow us to rethink responsibility and intervention, and to attempt to interrupt the cycle.

That is why I use shifts between three perspectives: the victim, the perpetrator, and the bystander, as both a narrative and an ethical strategy. This is not a defence of any side. Rather, it lets the same life reveal its contradictions and structural complexity from different positions, so the viewer can feel how an event is shaped by relationships, environment, and silence. It also returns the work to a more actionable question: how do we become bystanders, and at what moments might we, without noticing, move closer to perpetration, or slip towards victimhood?

Sound, especially low- and high-frequency audio, plays a central role in shaping embodied responses in your work. How do you use sound to access psychological states that are difficult to articulate through images alone?

I treat sound as a narrative tool that enters the body directly. It can bypass language and rational processing, letting sensation happen first in the body, and then deepening understanding in return. High frequencies are often felt as sharpness and tension, heightening alertness, while low frequencies can bring chest pressure and deep resonance. When these are combined with spatial audio, distance, direction, and movement paths can quickly draw the viewer into different layers of feeling, making sound especially effective for reaching states that are hard to put into words, such as vigilance, oppression, dissociation, or fear held in silence.

I also use directional sound and bodily sensation, together with camera movement, to create a kind of “soul-switching” between three perspectives, so the viewer’s sense of self naturally shifts from one role to another. Finally, I deliberately leave space for what cannot be fully articulated, inviting the viewer to stay between what is already sensed and what is not yet speakable. Many experiences of violence, trauma, and coexistence are fractured at the level of language. For me, the value of immersive media lies precisely here: it allows these psychological states to be encountered and borne, rather than simply explained.

The Old Enemy, VR, 2025 © Yang-hsi Hsiao

The Old Enemy, VR, 2025 © Yang-hsi Hsiao

Many of your projects explore trauma not as a fixed event, but as something that circulates among victims, perpetrators, and bystanders. How does immersive technology allow you to examine this relational aspect of trauma?

I understand trauma as something that circulates. It doesn’t only happen to victims; it is also shaped and prolonged by perpetrators’ power structures, bystanders’ silence, and the social relationships surrounding an event. For me, the most important value of immersive technology is that it can translate these abstract relations into perceivable experiences of position, distance, and time, so the viewer can feel, at a bodily level, how they are implicated within them.

Through shifts in perspective and placement, combined with space, sound, and rhythm, I can show how trauma is pushed forward through interaction: approaching, enclosing, attacking and being attacked, being seen or being ignored. This means the audience is no longer merely an external observer, but is placed inside an ethical field and compelled to witness. In that sense, VR allows me to move the focus from “what happened” to “what mechanisms allow it to keep happening, and to become a destructive cycle.”

Diving Into the Wreck focuses on bystanders and subtle forms of intervention. What did behavioural psychology reveal to you about vulnerability and agency that surprised you during this research?

Behavioural psychology taught me that bystanders’ “vulnerability” is often not indifference, but the result of predictable psychological mechanisms, for example, uncertainty (am I misreading the situation?), diffusion of responsibility (someone else will handle it), social-evaluation anxiety (will I embarrass myself or become a target?), and fight-flight-freeze responses when a threat feels imminent.

It also helped me rethink agency. Agency doesn’t have to look like a dramatic intervention; it can be a small, designable, and practiceable choice, checking in with a single sentence to see if someone is safe, redirecting attention, creating a brief interruption, stepping closer to become a witness, or quickly bringing others in and seeking help. These low-threshold actions reduce the perceived cost of intervening, making it more feasible and more aligned with the constraints people face in real situations.

So the work is not about encouraging heroism. It focuses on how, within vulnerability and limitation, people can still retain “minimal but effective” action, and how the bystander position can become a pivotal turning point in the cycle of violence.

Diving Into the Wreck, Interactive XR, 2024 © Yang-hsi Hsiao

The metaphor of the mountain, holding everything without judgment, appears as a philosophical anchor in your work. How do you translate this idea into spatial design and sensory experience?

“Mountain” is where I grew up. When I was alone, I loved shouting into the mountains, because they would always answer with an echo, almost like proof that I existed. For me, the mountain is also a vessel that allows coexistence: the small and the powerful, the fragile and the violent can all find a place there, even within the same body, without having to be split apart, categorised, or judged too quickly. At the same time, the mountain offers concealment. You have to come close, even step inside it, to have a chance of seeing. It also holds a long timescale, bearing the slow sedimentation of causes and traces.

In The Old Enemy, the mountain is also part of the story in a literal sense. After the crime, the perpetrator retreats into the mountains, and over that period, his aggression is, to a certain extent, “regulated” and “settled”. I do not treat this as absolution. I treat it as a question: how does violence transform over time? In terms of spatial design, I translate the mountain into a path of circling and return, where sightlines are often blocked. In the oral history, people use the phrase “guidaqiang” to describe the experience of getting lost in the mountains. Even if you draw closer or keep searching, you may still not find a way out.

Through rapid shifts and movement of perspective, I ask the viewer to pass, within a short span, through different stages of a life, and through the weight of different roles. It shows how someone is harmed, then goes on to harm others, forming a cycle of violence. These shifts often create moral disorientation, but I see that disorientation as a necessary transitional state before understanding can emerge. When a single, stable moral narrative is opened up, complexity has a chance to be seen and, briefly, to coexist. My hope is that if viewers can stay with this uncertainty, then when they face events that keep recurring in the real world, they might gain a little more understanding and a little more space to breathe.

Diving Into the Wreck, Interactive XR, 2024 © Yang-hsi Hsiao

Diving Into the Wreck, Interactive XR, 2024 © Yang-hsi Hsiao

Looking ahead, what questions or emotional states are you most interested in exploring next, and how do you see your practice evolving within XR research and artistic contexts?

What I most want to explore is how complex emotions are generated across the body, relationships, and social norms,for instance, shame. Shame is both a form of self-evaluation and something shaped by an imagined gaze from others. Compared with fear or sadness, it is harder to put into words, yet it can have long-term effects on our boundaries of action, intimacy, and capacity for self-repair. What I care about is whether, without causing further harm or romanticising shame, we can create an experience in which shame can be seen, held, and gradually loosened.

At the same time, I’m exploring the possibility of XR as a “psychological technology of imagination”, one that allows people, through the embodied, being-placed-inside quality of sensory experience, to rehearse their position, boundaries, and inner narratives anew.

Looking ahead within both XR research and artistic contexts, I hope my practice continues to move towards research-based creation, bringing together an understanding of behavioural and emotional mechanisms, ethical and trauma-informed design methods, and a more rigorous dialogue between aesthetics and experience differences that can be observed and reflected upon.

Lastly, we are witnessing massive and rapid changes in technology, from AI to increasingly immersive digital environments. How do you see these shifts influencing your practice today, and how might they shape the direction of your future projects?

I see AI and increasingly immersive digital environments as an accelerator. Through simulation, generation, and rapid iteration, they have changed both the speed and the way I externalise ideas into prototypes. Most directly, they allow me to produce multiple versions of visual and scenario sketches much faster, so I can devote more time to the experience design itself, how perspectives shift, how sound is positioned, how rhythm guides attention, and how the viewer’s psychological safety is held.

Looking ahead, I’m more interested in whether these technologies can give a work both scalability and intimacy: the capacity to respond to larger social contexts while also being adjusted to individual experience. AI’s real-time feedback may make that kind of adjustment more systematic and cumulative, especially when working with hard-to-articulate emotions and relational structures. I hope to combine AI’s iterative capacity with XR’s embodied experience to develop creative methods that are more responsive, more adjustable, and more trauma-informed.

Finally, The Old Enemy and Diving into the Wreck are still in development, and I warmly welcome institutions and individuals who are interested in supporting and collaborating through technical partnership, resources, or sponsorship.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a curated promotional platform that offers artists the opportunity to articulate their vision and engage with our diverse international readership through insightful, published dialogues. Conducted by Mohamed Benhadj, founder and curator of Al-Tiba9, these interviews spotlight the artists’ creative journeys and introduce their work to the global contemporary art scene.

Through our extensive network of museums, galleries, art professionals, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide, Al-Tiba9 Interviews provides a meaningful stage for artists to expand their reach and strengthen their presence in the international art discourse.