10 Questions with Anna Moskalets

Anna Moskalets is a contemporary Ukrainian artist, independent curator, and social activist. Born in Romny (Sumy region, Ukraine), she is now located in London, UK.

Moskalets attended the Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts and completed a Contemporary Art discipline course at the Royal College of Arts. She worked at the Artem Volokitin and Tatiana Malinovska studio from 2014 to 2016 and became a laureate of the Goethe-Institut Visual Project Fund in 2022. She served as a cultural ambassador for panel discussions in the Bundestag and participated in an art project visited by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz as part of a cultural mission.

Moskalets has curated art projects in museums and contemporary art centres. As an artist, she represented the Ukrainian Pavilion at the 2019 Biennale and the Frieze LA VIP program in 2023. She exhibited at ART MIAMI and CONTEXT ART MIAMI during Art Basel Week 2024, as well as at Art Palm Beach.

She has participated in more than 30 solo and group projects across Ukraine, Italy, Spain, Germany, Portugal, Poland, Georgia, and the USA in museum and contemporary art centres.

Anna Moskalets - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

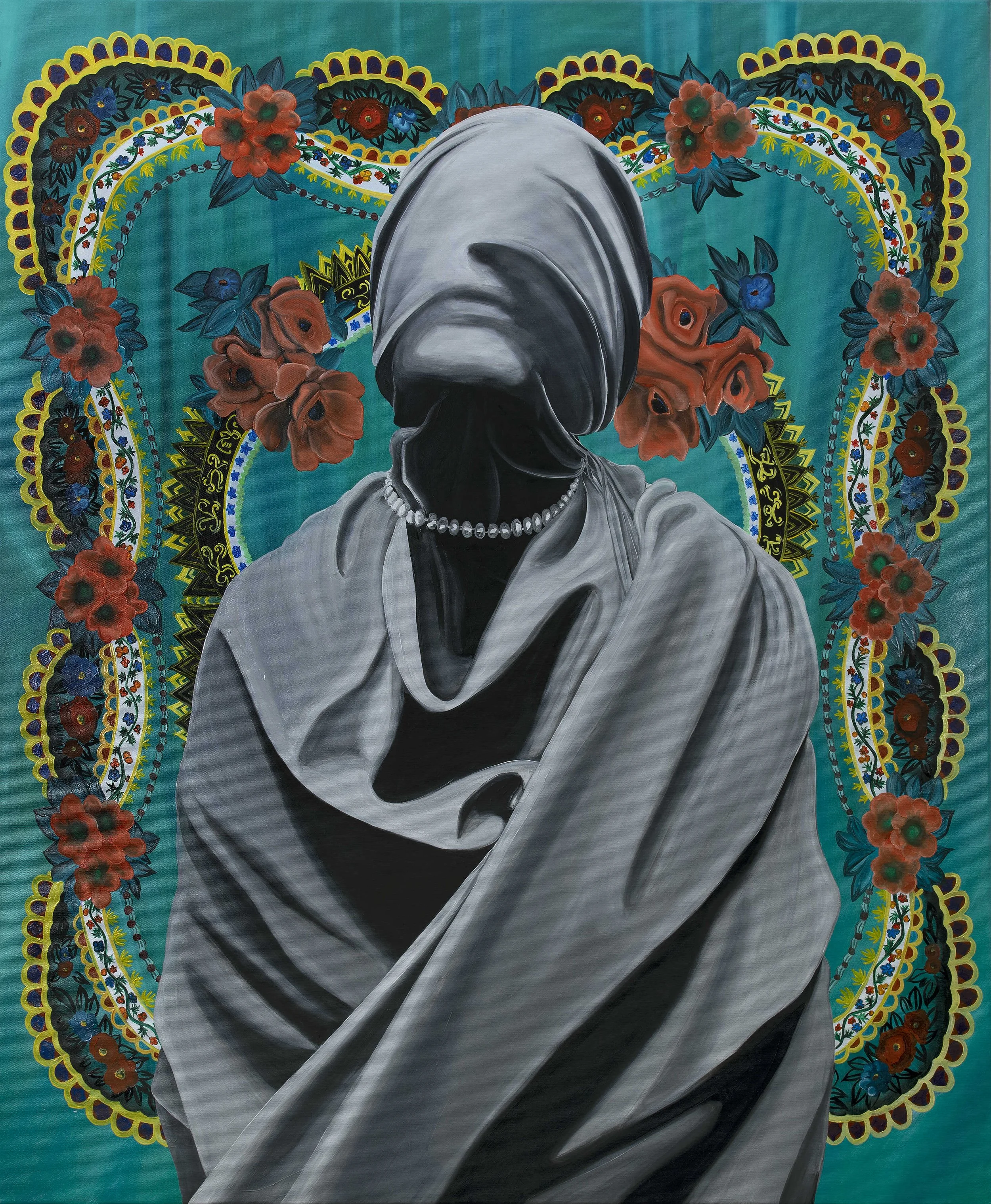

Anna Moskalets is a Ukrainian artist operating across the UK and Ukraine. Her artistic journey began with an in-depth exploration of heritage, ancestral memory, and belonging. Her early work visualised her grandmother’s headscarves, serving as a powerful symbol of generational continuity, an archive of experience, history, and identity passed through time. Over the years, her practice has evolved into a blending of these origins with contemporary reflections on belonging, memory, and self-discovery. By comparing her own life and experiences with those of previous generations, sometimes in historically similar contexts and other times in vastly different times, she seeks to uncover the universal threads that connect us.

Her work confronts urgent themes: displacement, resilience, and the search for identity. Forced to leave her homeland, Anna exists in a paradox: building a new life while bound by an unbreakable connection to Ukraine. This duality fuels her quest for emotional, psychological, and spiritual survival amid ongoing conflict. Her homeland’s perilous, compelling reality informs her art, shaping a fierce narrative of wartime strength, hope, and human endurance. Anna observes the frontlines of psychological and societal upheaval, where grief and happiness, chaos and calm coexist. Her art embodies this tension, raw and visceral, expressing rupture and continuity, disorder and harmony in the face of crisis.

Her practice explores the paradox of belonging, more urgent than ever, despite dislocation. It reveals unseen negotiations of love, hate, hope, despair, kindness, and futility. Through visceral imagery, Anna exposes the profound toll of displacement and the resilience of the human spirit. For Anna, adaptation is a form of recognition: a reconnecting with the idea that home and identity surpass borders. Her work is a bold, internal dialogue, an act of defiance, affirming her unbreakable bond to her roots. This journey shapes her layered, unpredictable practice, an exploration of identity, loss, and resilience expressed through paintings, collages, installations, and sound. Her art embodies the universal quest for belonging amid a fractured, uncertain world.

Rejuvenation, oil on canvas, 90x70 cm, 2024 © Anna Moskalets

INTERVIEW

Could you please tell us a bit about yourself? Who are you, and how did you become the artist you are today?

I'm a Ukrainian artist, originally from the Sumy region in the northeast of Ukraine. I lived in Ukraine most of my life, but after the start of the full-scale invasion, I moved to Germany, and now I live between the UK and Ukraine. This movement between places has deeply influenced both my outlook and my artistic practice.

I feel that I've been an artist for as long as I can remember. It didn't begin with a formal career; it began in childhood. I grew up surrounded by the beautiful, quiet landscapes of Ukrainian nature, and those early experiences formed the foundation of my visual language. Nature was my first teacher. The colours, the changing seasons, the atmosphere, these became the way I understood the world.

Later, living in several large Ukrainian cities added new layers to my perception, but that childhood connection to nature remained the basis of how I see and create. My relationships with older generations, my grandmother, and my mother also shaped me profoundly. I've always believed that people are deeply influenced by trauma, including the trauma we inherit. And in a paradoxical way, these inherited experiences can carry a certain kind of beauty. I began exploring these themes very early in life, before I even had the words for them.

My time in Germany and the UK expanded my artistic perspective further, giving me new contexts, new questions, and new artistic tools. Although my greatest love is oil painting, I also work with sound, installations, and mixed media. Over time, my artistic path has naturally led me to explore generational trauma, ancestral memory, and the feeling of belonging, how history lives in the body and how memory transforms into visual form.

This combination of personal history, movement between cultures, and connection to my heritage continues to shape the artist I am today.

Obscure, oil on canvas, 120x100 cm, 2025 © Anna Moskalets

Your artistic journey began with an in-depth exploration of heritage, ancestral memory, and belonging, as you mention in your statement, through your grandmother's headscarves. How did these headscarves become the foundation for your visual language, and how has that early symbolism evolved in your more recent work?

The most profound series in my practice is built around the visual reinterpretation of my grandmother's headscarves. Through them, I explore heritage, ancestral memory, and the sense of belonging. These headscarves became the foundation of my visual language because my grandmother has been one of the central figures in my life. I lived with her throughout my childhood, often even in the same room, and I always felt an intimate, almost instinctive connection to her. She is 88 now, and she has always worn headscarves in every stage of her life. Looking through photographs of her from different ages, this motif appears again and again.

In Ukrainian culture, especially historically, a headscarf is far more than a simple piece of fabric. It accompanies a woman through every stage of life. Babies were wrapped in headscarves; young girls wore them differently from brides; married women and elderly women had their own ways of tying and choosing them. The patterns, colours, and styles carried symbolic meanings, joy, mourning, transitions, and community roles. It is almost a separate visual language and tradition in itself, rich with codes and emotional depth. I've always been fascinated by how one square of fabric can hold so much meaning and how it reflects the entire lineage of women who wore it.

In my recent work, the symbolism of the headscarf is still present, but it has evolved. I continue to use its form as the core visual structure, but over time I've introduced new elements that reflect who I am today. This shift happened naturally as I tried to understand how ancestral memory shapes my present identity. My grandmother lived through the Second World War, and she still carries those memories. Now, as her granddaughter, I am living through another war, in a different era and under different circumstances. Our experiences are different, yet connected by the weight of history and the emotional resonance of conflict.

My newer works incorporate symbols and abstractions that express my contemporary experiences, new environments, migrations, cultural transitions, and the traumas of the present moment. The headscarf remains the thread that ties generations together, but the visual language around it has expanded to include my own voice, my own time, and my own way of seeing the world.

Nowadays, you work across painting, collage, installation, and sound. How do you decide which medium best conveys a particular idea or emotion? Do these media coexist within a single narrative, or do they each represent distinct stages of your process?

Although I work across painting, collage, installation, and sound, I see all these media as different languages for expressing the same core ideas. The concept always comes first, and then I choose the medium that can communicate a particular emotion or layer of meaning in the most honest way. Sometimes a visual form is enough; other times the idea needs sound, space, or a more tactile experience.

For example, in my sound works, I often use the singing of nightingales. This bird is deeply present in Ukrainian folklore and collective memory, and its singing carries meaning that changes with context, mourning, longing, joy, desire, andeven homesickness. In a way, I recognised something human in that: the nightingale communicates emotions through sound, the way I communicate through visual form. So sound became a way to express feelings of absence, distance, and cultural memory that couldn't be captured by painting alone.

In my installations, such as the series of cages, the physical structure becomes a metaphor. The cage represents "home" in a dual sense: a safe place, but also a boundary; a space of belonging, but also confinement. This complements the themes I explore in oil painting and collage, home, homelessness, belonging, and the tensions between past and present.

So yes, the media absolutely coexist within a single narrative. They are not separate stages but interconnected expressions of the same story. Painting allows me to work with inherited symbols; collage lets me fragment and reassemble memory; sound gives voice to emotion; installation creates an environment the viewer can inhabit. Together, they form a multi-layered exploration of heritage, displacement, and identity.

Lacuna, oil on canvas, 170x110 cm, 2022-2023 © Anna Moskalets

Lacuna 1.1, oil on canvas, 170x110 cm, 2020-2023 © Anna Moskalets

Your work often oscillates between chaos and harmony, rupture and continuity. How do you translate such emotional and psychological tensions into visual form?

In my work, I try to project the feeling of life itself, and life is rarely stable. It's a constant movement between chaos and harmony, rupture and continuity. I translate this emotional tension into visual form by staying completely honest with what I feel and observe. Honesty is essential because when the emotion in the artwork is real, the viewer can sense it.

If an image or idea doesn't resonate with me, if it doesn't belong to the state I'm actually in, I can't use it. Instead, I try to show the viewer something genuine: "This is me, this is my reality, these are the beautiful moments and the difficult ones." I believe that when you offer this kind of sincerity, something universal appears. My experiences are not unique; many people carry similar emotions, even if they express them differently.

I value the moment when someone looks at my work and feels something they can't quite articulate, an emotional echo, a recognition. It's as if they're saying, "I don't know you, but I know this feeling." That sense of connection between strangers is incredibly meaningful to me.

By combining opposing elements, calm and chaos, fragmentation and continuity, I'm reflecting the contradictions of being alive. Life itself is made of contrasts, and I see myself as a product of that complexity. My hope is that viewers can see their own inner tensions mirrored in mine, and feel understood, even for a moment.

Displacement and belonging are central to your practice. Living between Ukraine and the UK, how has this dual existence shaped your sense of identity as both an artist and a person?

Living between Ukraine and the UK has shaped me profoundly, both as an artist and as a person. Movement has been a part of my life since childhood. I left home at fourteen to study, then moved again at sixteen, then again for work, and eventually to different countries. Sometimes these moves were chosen, and sometimes they were forced. Each type of movement shapes you differently because the motivation behind it carries its own emotional weight.

This continuous displacement opened many different edges of my identity. As an artist, it pushed my practice to become more complex and more emotionally layered. If I had stayed in one place, my work might have remained very consistent, perhaps even too consistent. But being in motion, especially under the pressure of circumstances beyond my control, filled me with a range of emotions that inevitably find their way onto the canvas.

This dual existence brought me grief, longing, and a quiet sense of guilt, this feeling of being a "betrayer," even when I knew I had no choice but to leave. At the same time, it brought experiences of freedom, renewal, and the desire to return. It made me feel both framed and unframed, rooted and uprooted, harmonious and unsettled. All of these contradictions have become a vital part of my artistic language.

I don't yet know where this journey will end, but I feel that one day I will return to the place where it all began. There is a circle in my life that I sense will close at some point, and that completion, both as an artist and as a human being, feels meaningful to me. For now, my journey continues, and I try not to resist it. Instead, I accept it and use it to create, to reflect, and to express as fully as I can.

Sitanok 1.2, oil on canvas, 100x70 cm, 2025 © Anna Moskalets

Your art carries both personal and political dimensions, particularly in relation to the ongoing war in Ukraine. How do you navigate the fine line between personal expression and collective representation?

For me, the line between personal expression and collective representation is very thin, almost nonexistent. I realised that my individual experience is, in many ways, a collective one. I am Ukrainian, and the circumstances I've lived through are shared by millions of people from my country. So when I speak about my own story, I am also speaking about the stories of many others.

I choose to be honest and bold, because what I care about is too important to stay silent. In times of war, silence is dangerous. The aggressor, Russia, uses propaganda as one of its strongest weapons, sometimes even more powerful than physical violence. I'm not a soldier, but I do have the ability to use my art as a form of truth-telling. I can speak about what I actually lived through, not what I heard, not what I saw on television, but what I personally experienced. And I believe I have the right to share that truth with the world.

Whether the world wants to listen is not something I can control, but it is my responsibility to speak, especially for those who cannot. Many Ukrainians don't have the opportunity, the platform, or even the safety to express what they are going through. If I have that privilege, and I do, I feel it is my duty to use it.

I also believe that art is inherently political because it reflects life, and life is shaped by political realities. I am an artist, but before that, I am a human being with a home, a family, and friends who are in danger. A tragedy is happening, and pretending that art must remain apolitical does not feel honest or ethical to me. Art can be a powerful weapon, and I choose to use it. It is not only my right, it is my honour and my responsibility.

You've also worked as a curator and cultural ambassador, participating in projects recognised at the Bundestag and the Goethe-Institut. How does curating influence your perspective as an artist and vice versa?

Working as a curator and as a cultural ambassador has shaped me in different but equally significant ways, and both roles deeply influence how I think and create as an artist.

As a curator, I step outside of my own practice and look at art through a broader cultural and conceptual lens. Curating exhibitions, especially in contexts such as the Bundestag or the Goethe-Institut, requires me to understand how artworks speak to one another, how narratives are built, and how the audience enters the experience emotionally and intellectually. This expanded perspective feeds back into my own work: it helps me understand how my pieces might exist within larger conversations about history, identity, and memory. Curating teaches me the importance of structure, precision, and storytelling.

As a cultural ambassador, the experience becomes even more profound and emotionally charged. Representing Ukrainian culture abroad, especially during wartime, holds enormous responsibility. It requires me not only to express my personal story but to speak for a broader collective, to bring attention to voices that are often unheard, misrepresented, or overshadowed.

One of the most transformative aspects of this role has been learning about conflicts around the world. When you represent your country in international cultural spaces, you inevitably meet people who carry their own histories of war, displacement, oppression, or silence. You begin to see how interconnected global tragedies are, and how similar the emotional landscapes of loss, migration, and resilience can be, even if the geopolitical contexts differ.

This experience taught me something crucial: if you want the world to pay attention to the conflict in your home, you must also pay attention to the suffering happening elsewhere.

This mutual awareness creates empathy, solidarity, and a shared vocabulary of experience. It prevents you from feeling isolated in your pain and helps others see Ukrainian tragedy not as a distant geopolitical issue, but as part of a global human story.

As a cultural ambassador, I learned to listen deeply, not only to speak. I learned the importance of acknowledging thewounds of others while advocating for my own. This perspective allowed me to build bridges, not only between cultures, but between traumas. It made my mission stronger, more grounded, and more ethically aligned.

These two roles, curator and cultural ambassador, continuously shape my artistic practice. Curating gives me professional distance, conceptual clarity, and a critical framework. Cultural ambassadorship gives me emotional depth, cultural responsibility, and a profound understanding of how personal stories become collective narratives.

Together, they enrich the art I create and the way I navigate my identity as both an artist and a human being.

You've exhibited internationally, from the Ukrainian Pavilion at the Biennale to Art Miami and Frieze LA. How has the reception of your work changed across these cultural contexts? Do audiences in different places respond to your themes in unique ways?

Exhibiting internationally has been an eye-opening experience because it allows me to observe how people from different cultures interpret my work through the prism of their own histories, identities, and emotional landscapes. Sometimes the reactions align with what I expect, and sometimes they completely surprise me.

For example, I am Ukrainian and European, so naturally I feel very understood in Europe. Audiences here share similar cultural references and a related historical background, so there is a kind of immediate emotional connection. Even though each country has its own nuances, I always feel that we "speak the same visual language."

But then there are moments that are unexpected, like the reception of my work in Miami. Culturally and historically, Miami is very different from where I come from. Yet the feedback there was incredibly warm and deeply engaged. People connected with my themes of memory, displacement, belonging, and emotional tension, even though their own context isdifferent. It reminded me how universal certain emotions can be, and how art can build bridges between very distant experiences.

Through international exhibitions, I realised that the world is both enormous and very small. You can find emotional similarities in places you never imagined. You recognise yourself in others, and others recognise themselves in you. That sense of being "understood," "seen," or at least "intriguing" to viewers is powerful, and I believe that intrigue is one of the strongest forces in contemporary art. When I see people leaning in, trying to decode their own emotions through my artworks, I feel that the work has succeeded.

I also believe that the artist should be present whenever possible. Sometimes viewers say things like, "I imagined the artist was a man," or "I interpreted this figure as male even though it represents a woman." These reactions show how much duality and ambiguity live inside our perceptions, and how viewers sometimes project their own assumptions onto art. Hearing these interpretations enriches my understanding of how my visual language operates in different cultural spaces.

Overall, the reception of my work varies in fascinating and unpredictable ways depending on the region, culture, and historical context. Observing these differences feels like studying a kind of emotional and cultural science, revealing how art travels, transforms, and resonates across the world.

Memory plays a pivotal role in your practice, both as an archive and as an active force. How do you approach the idea of memory in a time when collective histories are being rewritten or erased?

Memory is absolutely essential in my practice, because for me it is deeply connected to authenticity. And authenticity is something very rare and very expensive in the world of art today. I believe art becomes truly successful only when it is honest, when you don't hide behind trends or expectations, but show yourself as you are.

When people come to see my work, I want them to remember me. And they will remember me only if I'm honest with them, if I say: "Listen, this is my story. Some pages are bright, some are painful. But this is how I was shaped, this is how I was built, do you like it or not, this is me."

I think that this honesty speaks to many people, because we live in a moment when everyone is becoming "international,"constantly moving, adapting, blending in. But the world is beautiful exactly because we stay true to who we are. That is what creates diversity, depth, and meaning.

We currently live in a time when histories are rewritten, manipulated, or simply erased. And for me, memory becomes a way of resisting that. By archiving myself, my experiences, my voice, my emotions, I enter history in a way that cannot be erased. My memory is also part of the memory of my culture, my family, and my land.

At the end of the day, I don't want to become "British," or "German," or "American," or anything else the world might expect me to become. I want to remain myself. I want to remain Ukrainian. And my art is the space where that memory is protected, lived, and carried forward.

Eksteza, oil on canvas, 120x100 cm, 2023 © Anna Moskalets

Noir Gold, oil in canvas, 120x90 cm, 2024 © Anna Moskalets

Lastly, looking ahead, what directions or projects are you most excited to explore next? Are there new media, collaborations, or themes you feel drawn to in this next phase of your artistic journey?

Yes, definitely. As I mentioned earlier, even in difficult times, good things can still grow. These past few years of living abroad have given me new connections, genuinely meaningful ones, with artists whose practices inspire me and whose perspectives challenge my own. I love that. I'm very drawn to the way they see the world, and these encounters opened new directions for me.

I'm now planning several collaborative projects with artists from the UK, France, Germany, and Ukraine. We want to explore shared themes, but each of us filters them through our own experiences and artistic languages. This kind of dialogue feels important to me; it creates a space where differences don't divide but deepen the work. I hope to bring these projects to Ukraine eventually, but they will also exist internationally.

At the same time, I'm working more actively with the theme of the military, especially camouflage. For me, camouflage is not only about war; it's about survival and about navigating modern life. Military patterns carry layers of meaning for so many people today. The deeper I dive into this topic, the more I understand its emotional and symbolic weight. I have my own material and my own lived experience, so I feel ready to engage with it honestly. In fact, I'm already working on it, and it makes me feel alive.

I don't want to describe every detail of my plans, because life is unpredictable, sometimes even from morning to evening. But this is the direction I feel drawn to right now: building international artistic conversations around shared themes, and continuing to explore the military and camouflage topic as a lens for understanding both conflict and contemporary existence.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a curated promotional platform that offers artists the opportunity to articulate their vision and engage with our diverse international readership through insightful, published dialogues. Conducted by Mohamed Benhadj, founder and curator of Al-Tiba9, these interviews spotlight the artists’ creative journeys and introduce their work to the global contemporary art scene.

Through our extensive network of museums, galleries, art professionals, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide, Al-Tiba9 Interviews provides a meaningful stage for artists to expand their reach and strengthen their presence in the international art discourse.