10 Questions with Nebras Hoveizavi

Nebras Hoveizavi (b. Ahvaz, Iran) is an Arab-Iranian artist and educator working across experimental film, photography, installation, and poetry. After earning her B.F.A. (2014) and M.F.A. (2016) in Photo/Media from the California Institute of the Arts, she developed a multidisciplinary practice rooted in the transformation of language into image. Currently based in Qatar, where she teaches film and photography, Hoveizavi's work has been exhibited internationally, including "Body Politics" at the Whitechapel Gallery (London) and "Cinema Iran: The 6th Edition" (Munich). Originally trained as a poet writing in Farsi, migration disrupted her relationship with language, leading her to develop a visual vocabulary as an alternative form of expression. Her films, photographs, and installations function as poetry translated into visual form. Hoveizavi's practice engages with displacement, memory, borders, and the limits of language. Working across photography, video, and experimental media, she approaches image-making as a form of witnessing, transforming observation into a visual language shaped by lived experience. What could no longer be expressed through words found its way into images, where looking, sensing, and recording became an alternative vocabulary. Central to her work is the experience of relocation and disorientation, the coexistence of familiarity and estrangement. She questions fixed notions of borders, viewing them as imaginary constructs that shape identity and memory. Currently, Hoveizavi is reconnecting with writing, developing poetry and short stories alongside her visual work, allowing language and image to inform and reshape one another.

Nebras Hoveizavi - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Nebras Hoveizavi is an artist whose practice engages with questions of displacement, memory, borders, and the limits of language. Working across photography, video, and experimental media, she approaches image-making as a form of witnessing, transforming observation into a visual language shaped by lived experience. Originally trained as a poet, Hoveizavi’s relocation disrupted her relationship with words. What could no longer be expressed through language found its way into images, where looking, sensing, and recording became an alternative vocabulary. Her visual practice emerged from this gap between speech and silence, translating social, political, and philosophical concerns into visual form. Central to her work is the experience of relocation and disorientation, the coexistence of familiarity and estrangement. She questions fixed notions of borders, viewing them as imaginary constructs that shape identity and memory. The geography of memory, in her practice, does not consist of borders but of traces and fragments carried across places. Currently, Hoveizavi is reconnecting with writing and poetry, developing short stories and a novel alongside her visual work, allowing language and image to inform and reshape one another.

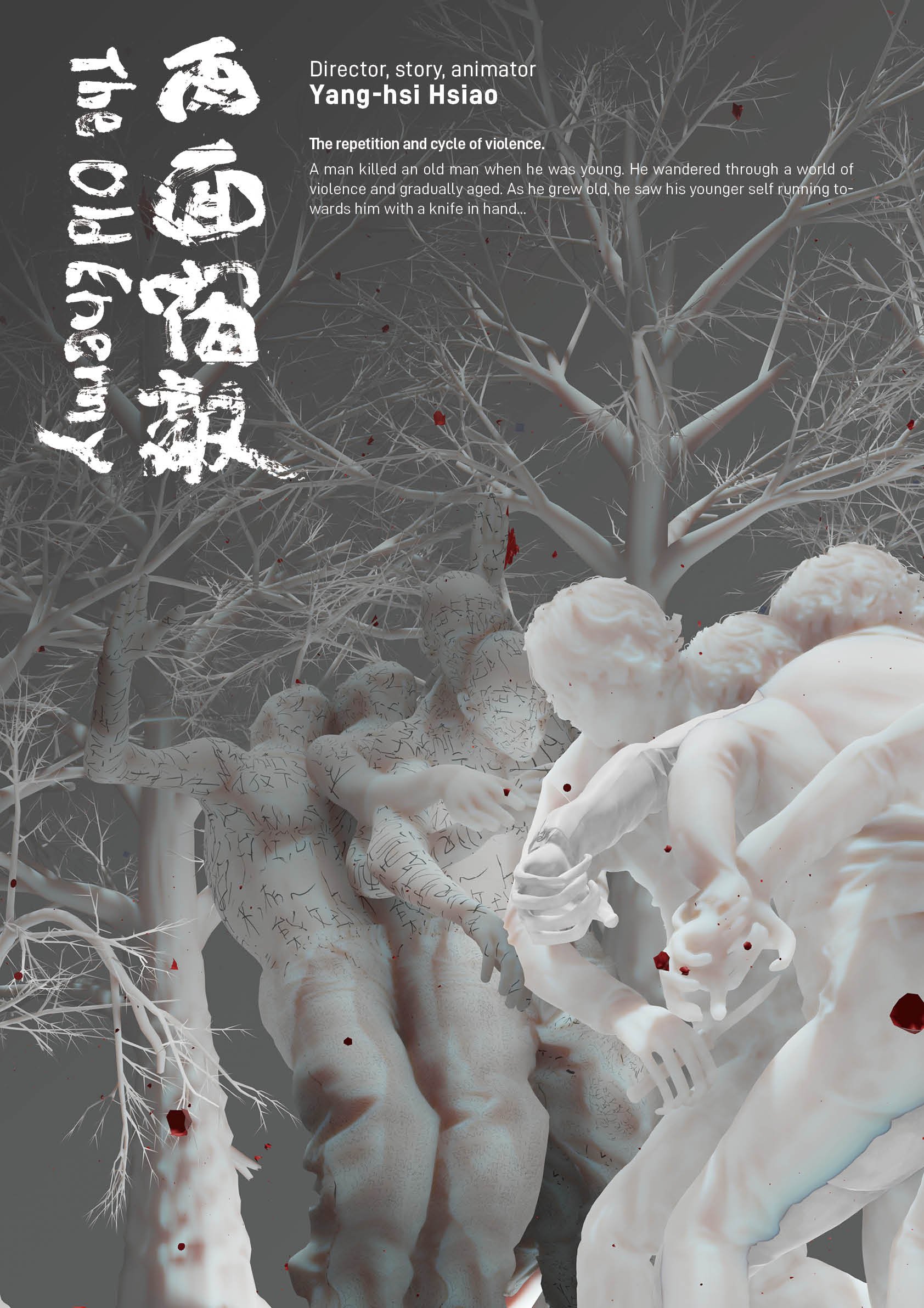

Sometimes in January, or Maybe June, Digital photograph, 90 × 60 cm, 2016 © Nebras Hoveizavi

INTERVIEW

You originally trained as a poet before turning to photography. What led you to embrace photography as your main form of expression, and what did images allow you to say that words could not at that time?

When I moved to the U.S., writing poetry slowly faded, and I almost lost the language of writing in Farsi. English became essential for finding work and attending university. I took a black-and-white photography course at Irvine Valley College, which significantly shifted my practice from poetry to photography, though the majority of pictures I took during this course were visual stagings of my poems. I would say the lack of English fluency and not knowing how to communicate pulled me deeper into visual language and gave me the words I was missing in English. As anyone who grew up in Iran during the 1980s and 1990s might know, we learned very limited English at school. Most of what I learned came from cartoons. Farsi, however, became very bold and present in my life. The language of poetry, I don't think, has ever faded or been lost in me; it has simply shaped and reframed itself differently.

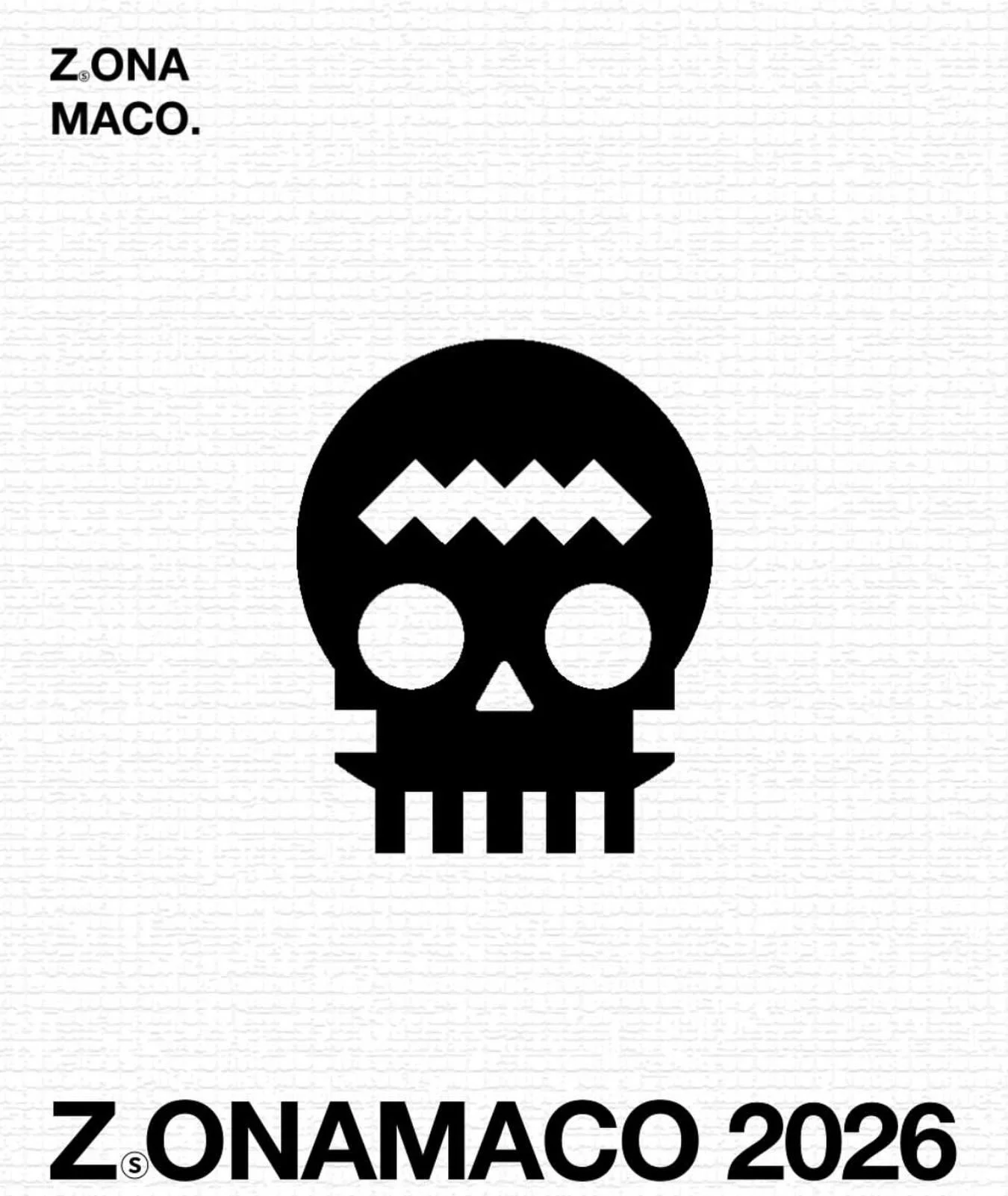

Border Run, Digital photograph , 120 × 80 cm, 2025 © Nebras Hoveizavi

You studied Photo/Media at CalArts, an environment known for experimentation. How did your time there influence your approach to photography and later to moving images and installations?

I think CalArts played an important role in my artistic practice. When you enter CalArts, they break down everything you thought you knew about art, and then you begin putting all the pieces together to create your own work. The fact that at CalArts we could have mentors from different departments added immensely to my experience and understanding of art. I had mentors from the Experimental Animation department and the Film department, and I even took classes in those areas. This naturally led me to take risks in my practice despite the fact that the art market is not always a fan of experimental work, which has many ups and downs. Your work might not fit the specific forms that are expected, but that's what I learned at CalArts: you will break down many times, but that's all part of the practice.

You were born in Ahvaz and now live between Asia, California, and Qatar. How has this movement between places shaped the way you see and make images?

Being born and raised in the Middle East (West Asia) has influenced me so deeply that I feel this region breathes under my skin, no matter where I go, the land is with me. I moved back to West Asia intentionally; I felt that if I'm talking about this land, I have to feel it and breathe it every day in order to have a good understanding of it. However, I wasn't able to survive in Iran, so I looked for another place to live in the region, and now I'm living in Qatar. What's very interesting is that the city I live in here, Al Khor, is almost visually identical to the place where I lived as a child, Ahvaz. It's also associated with oil and gas, just like my hometown. I think I've been very inspired by all these movements and by observing different lands. I believe that a land, no matter where we travel or go, holds so many stories and histories, which is fascinating.

Border Run, Digital photograph , 120 × 80 cm, 2025 © Nebras Hoveizavi

Border Run, Digital photograph , 120 × 80 cm, 2025 © Nebras Hoveizavi

Your practice expanded from photography into video, performance, and installation. Was this a gradual shift, or did a specific project or moment push you in that direction?

I think every project requires different forms of art. For example, in the past years, I've been working on a project called Border Run, which was based on an experience I had before coming to Qatar. Since some of the footage I recorded could reveal too much about the place, I had to choose animation and performance to recreate or let's say, construct the images differently. It was new and challenging since I had never done animation before, but I really like to learn while I'm making my work because I feel this is also part of the practice.

Many of your works engage with displacement, borders, and memory. How do these themes emerge in your projects? Do they come from personal experience, research, or a mix of both?

I would say my projects often start from personal experience, and through research, I'm looking for the bigger picture of how that experience has played out throughout history or for other individuals, and how it affects and shifts our surroundings and what questions it raises.

Can you describe how you typically develop a project, from the first idea to the final form? What role do intuition and structure play in your process?

As I mentioned earlier, my projects often start from personal experience. Then I take time with research about the idea and the possible ways I need to learn or work to present it. It may start with some archival images and videos that I've recorded, and I go through them to understand the work. Then I started writing about it. The language is sometimes poetic, and sometimes it shifts to stories. I let the writing be freer. These writings are often not essays, trying to capture a topic through different analyses. From writing about the topic, I become clearer about how I want to work on a project. However, editing video is a huge part of my work. Working on the sound and video footage is almost like sculpting and shaping flat wood into something. I often prefer to edit and create my own sounds, since during editing, another experiment of the project emerges. It's very similar to writing poetry, but in video, you may not have as much control over the process since it's technical and sometimes involves new technology. I feel it takes things out of my hands, which I also enjoy. But with poetry, it's me, a pen, and paper, and I'm more in charge of the text.

I Don’t Know You But I Will Frame You, Digital photograph (work in progress), 120 x 80 cm, 2025 © Nebras Hoveizavi

I Don’t Know You But I Will Frame You, Digital photograph (work in progress), 42 × 59.4 cm, 2025 © Nebras Hoveizavi

Teaching has been an important part of your career, from Iran to Qatar to the U.S. How has your experience as an educator influenced your own artistic practice?

I think I learn a lot from teaching. The reason I feel I need to learn while making projects is partly because of my day-to-day job as a teacher; being involved and asking students to be risk-takers is part of what the photography coursework curriculum requires. In addition, I like to observe my daily life as a teacher. For example, the new work I'm working on, “I Don't Know You but I Will Frame You”, is my self-portrait as a teacher, even though you only see a backdrop stand in the middle of a farm, or desert, or in a hotel room. This backdrop is something we use almost daily as photography teachers; we take it from the corner of the room, install it, and then put it back again. It's very interesting when I was showing this work to one of my Qatari students, he said, "Miss, this is so much you." But it's not obvious in the project since it's not a direct self-portrait. And the hotel is the life of an expat. We live here, perhaps sometimes more comfortably than where we're coming from, but we don't know for how long. It's also very unstable. The hotel room breaks the land, which seems to make you like an owner of something, yet it's actually the most temporary living moment.

Your work has been shown in very different contexts, from London to Tehran. How do you perceive audience reception across these spaces, and does it affect how you think about your work?

Since my work often has a very poetic and also political approach, in every location it might be read differently. But I like these layers of reading the work. This is how you experience a new language. And this is very valuable: that my work can be read differently.

Recently, you've been reconnecting with writing and poetry alongside your visual practice. How do language and image interact in your work today?

Working as a teacher is not easy; it's like never-ending work and occupies the majority of my time. During these past years, I've realized that editing videos in my free time and on weekends is very hard. Video, for me, is like wet clay. I feel you have to make it while the clay is not dry, and that requires time and freedom in your schedule, which, during the school calendar, is impossible. However, writing sometimes needs that pause, and it's actually good to write every day and come back to the text on the weekend. I feel the text shapes differently and sometimes even becomes stronger. Currently, I'm working on a text which I'm hoping to turn into a novel. I'm thinking a lecture performance might be a more suitable medium for this project. The text and animation, I feel, have some similarity, they both create a thought out of pieces of paper. They capture what you miss capturing on camera.

Ungrounded, Medium format photograph, lightbox, 42 × 59.4 cm © Nebras Hoveizavi

Lastly, what are you currently working on, and what directions or questions are you hoping to explore in your future projects?

Currently, I'm working on two projects. One is an ongoing photography project I started in 2025 called I Don't Know You but I Will Frame You. The other project I'm working on is called A Daughter's Archive, which I'm hoping to turn into a novel and video installation. This work is basically a novel about a woman who was born and lived in Ahvaz and is now turning 60. Chapter 1 starts with understanding a little about her and knowing she is not living in her house; she lives in the U.S. with her sister. As the chapters go on, we realise her life has been more complex than the day-to-day we expected. Among her daily thoughts, she explores the life she has passed through: being 12 years old when the revolution started, 13 or 14 when the war began, her marriage, her daughters, her business, and moving to the U.S. While she is exploring her process, the reader or audience also explores the history and politics of Iran from the point of view of a businesswoman who seemingly had it all and lost it all. I'm hoping this project will be ready by this September for my upcoming exhibition in Brussels.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a curated promotional platform that offers artists the opportunity to articulate their vision and engage with our diverse international readership through insightful, published dialogues. Conducted by Mohamed Benhadj, founder and curator of Al-Tiba9, these interviews spotlight the artists’ creative journeys and introduce their work to the global contemporary art scene.

Through our extensive network of museums, galleries, art professionals, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide, Al-Tiba9 Interviews provides a meaningful stage for artists to expand their reach and strengthen their presence in the international art discourse.