10 Questions with Mark James Murphy

Mark James Murphy is a contemporary British printmaker originally from Sunderland, North East England, and currently based in Vũng Tàu, Vietnam. His practice centres on the linocut, a labor-intensive relief medium he utilises as an "Anchor of Attention" against the velocity of modern life. Self-taught in the medium, Murphy explores the stillness and wonder found within the overlooked details of architecture and urban environments. By applying the industrial heritage of his home region to contemporary scenes in Southeast Asia, Murphy creates a visual dialogue exploring place, memory, and cultural assimilation. His work addresses the tension between physical settings and the emotional permanence forged through the slow, rhythmic carving process. Murphy’s work is held in international private collections. Recent and upcoming highlights include the Quintessentially British showcase in Ho Chi Minh City (2025), the International Printmaking Exhibition in New Hampshire (2026), and a feature in The Woven Tale Press (New York). Through his deliberate process, he transforms the ordinary into a profound meditation on the contemporary human experience, bridging the gap between his Northern English roots and his life in Vietnam.

Mark James Murphy - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Mark James Murphy’s practice is an inquiry into the physicality of memory and the resilience of the handmade. Rooted in the industrial heritage of Northern England, his work utilises the labour-intensive rhythm of linocut printing as an "Anchor of Attention" against the velocity of the digital age. Each hand-carved block serves as a site of resistance, where the repetitive, visceral motion of carving becomes a meditative act of storytelling. Working with traditional tools and oil-based inks, Murphy explores the quiet mysteries embedded within landscapes, architecture, and the urban fabric of Southeast Asia. His work utilises bold tonal contrasts and layered textures to reveal the emotional permanence of familiar spaces. By capturing the way time and memory settle into physical surfaces, he invites the viewer into a state of heightened perception. For Murphy, the linocut is more than a medium; it is a conceptual counterpoint to modern noise. Through the "echo of repetitive motion" and the deliberate marks of labour, he elevates the ordinary into a profound visual dialogue. His practice ultimately gives form to a sense of wonder, finding deep narrative significance in the fleeting moments and overlooked details of the contemporary human experience.

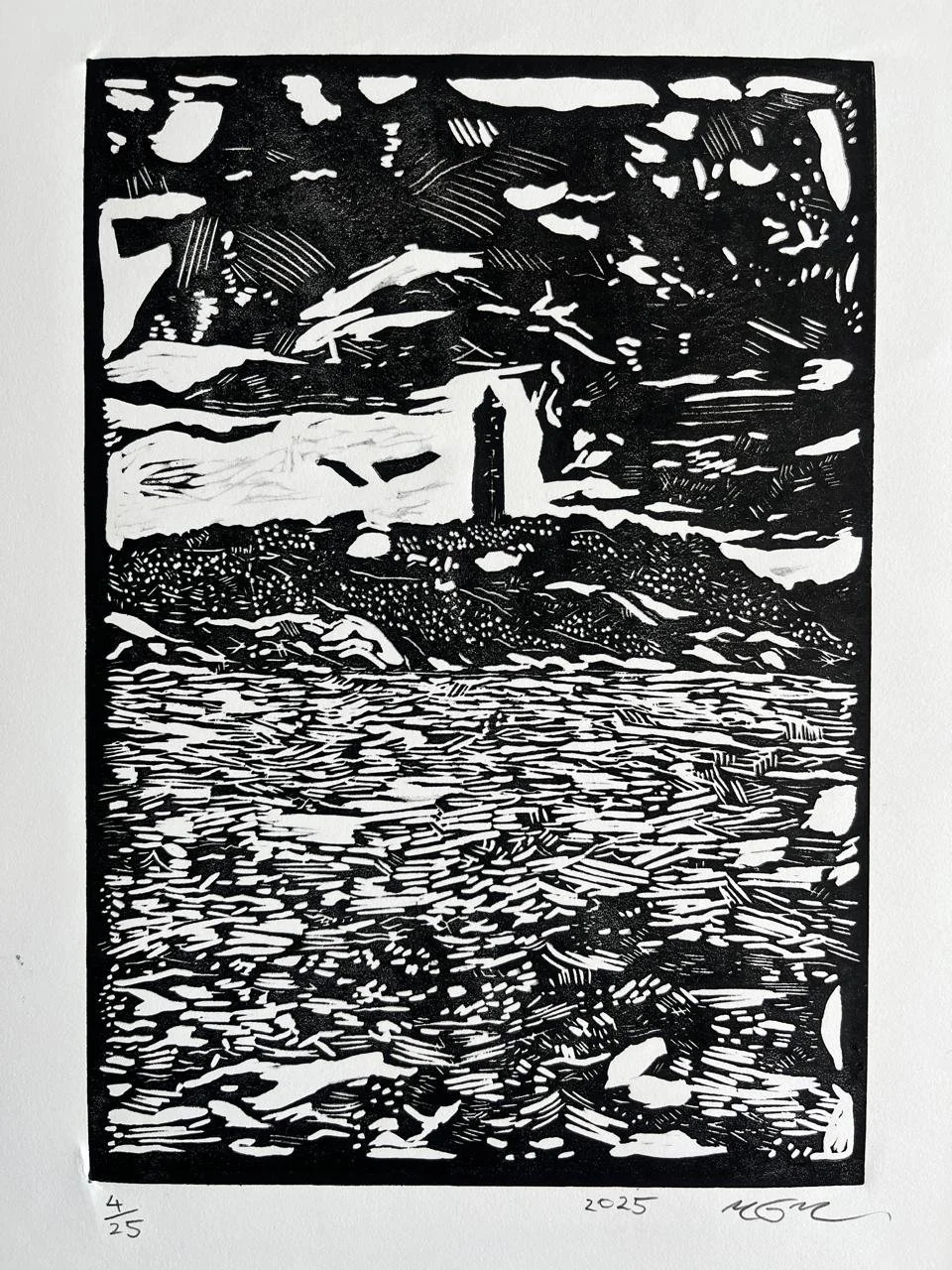

Ke Ga lighthouse, Binh Thuan province, linocut, 19.2 x 27.5 cm, 2025 © Mark James Murphy

INTERVIEW

Let’s first introduce yourself to our readers. Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your artistic background?

I am a British artist and printmaker from Sunderland, now based in Vũng Tàu, Vietnam. My background is rooted in the industrial North East of England, where labour and physical materiality were part of the landscape. This 'work ethic' followed me to Southeast Asia, where I now use the linocut to document my experience of assimilation. I find Haruki Murakami’s philosophy deeply resonant: the idea that art must be an honest manifestation of one's internal world to be 'true.' My work is less about capturing a scene and more about externalising the quiet, internal dialogue between my roots and my current home.

My background is a blend of formal academic training and independent technical discovery. I studied Fine Art at the University of Sunderland, which gave me a strong foundation in art theory. However, my journey into the specific world of relief printmaking was entirely self-directed. This combination allows me to approach my work with a degree of conceptual rigour while maintaining the raw, experimental energy of an artist who has had to learn the 'language' of their medium through trial and error.

You are self-taught in linocut printmaking. How did you come to work in this medium, and what drew you to it initially?

Despite my formal education in Fine Art, I didn't discover the linocut until I sought a medium that felt more grounded and physically demanding. I was drawn to the idea of transforming a material through a physical process; it felt like a return to the industrial work ethic I grew up around in Sunderland. Being self-taught in this specific medium allowed me to bypass traditional 'printmaking rules' and develop my own relationship with the lino. I initially chose it for its accessibility, but I stayed for its resistance. There is a physical tension in the carving; you have to learn every line. It forces a slower, more deliberate approach that other media simply don't demand.

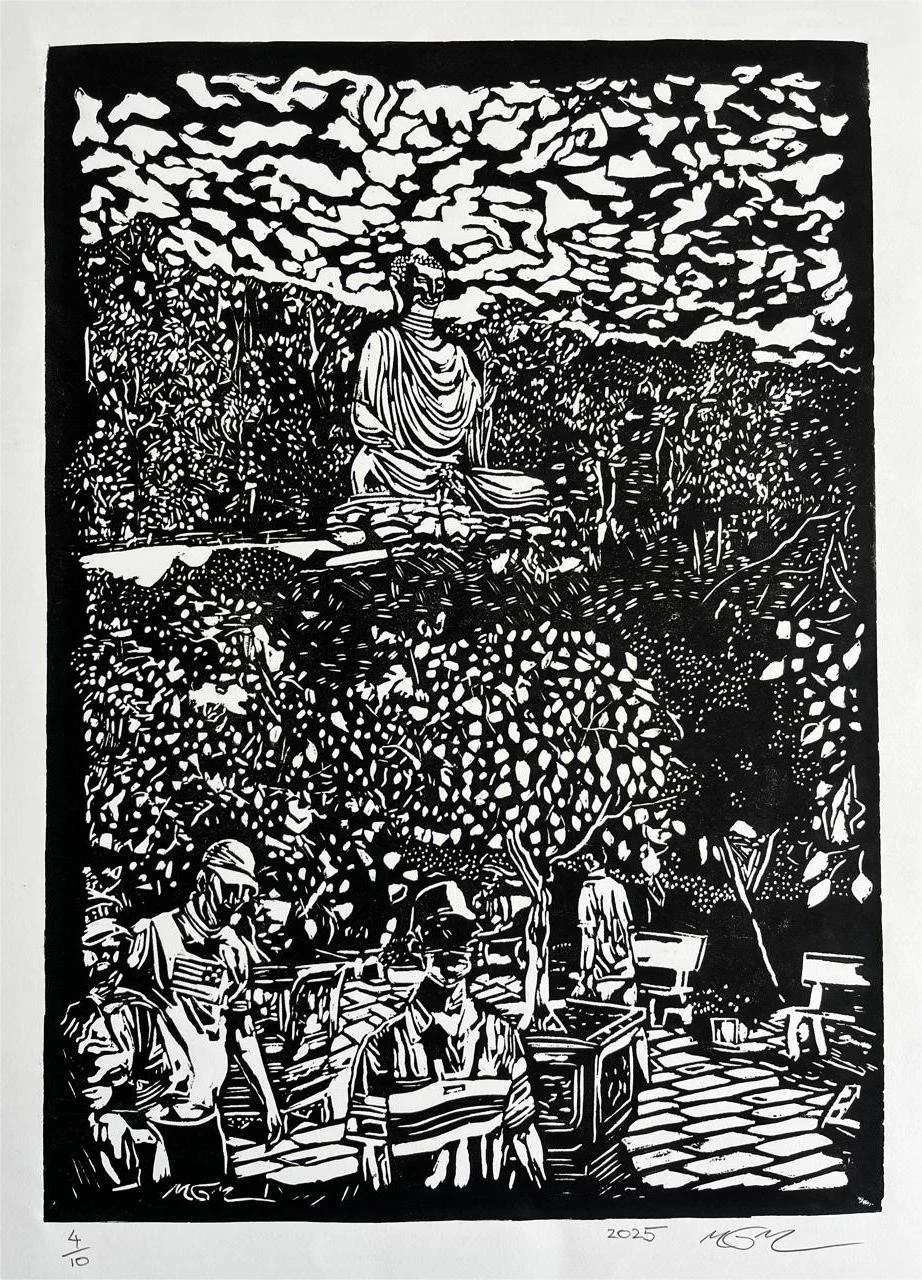

Chon Khong Zen Monastery, Vung Tau, linocut, 45 x 31.5 cm, 2025 © Mark James Murphy

Why do you describe the linocut as an “Anchor of Attention,” and what does the technique allow you to explore that other media cannot?

I describe the linocut as an 'Anchor of Attention' because it functions as a site of resistance against the velocity of modern life. Unlike digital media, which is built for speed and infinite scrolling, a linocut requires a singular focus for hours on just a few square inches of material. For me, the linocut is not just a medium; it is a conceptual counterpoint to modern speed. This technique allows me to explore emotional permanence in a way photography cannot. While a camera captures a split-second, a linocut block holds thousands of rhythmic decisions and physical struggles, creating a visual density that reflects how we actually 'feel' a place over time rather than just how we see it. Living in a rapidly developing city in Vietnam, I am constantly surrounded by digital noise, LED screens, hyper-connectivity, and the flickering velocity of urban change. My work acts as a physical filter for this environment. By reducing these chaotic scenes to a silent, monochromatic linocut, I am creating a sanctuary for the eye. The 'Anchor of Attention' is not just about the craft; it is a vital survival strategy for maintaining mental clarity in an increasingly digitised world.

Your work often focuses on overlooked architectural and urban details. How do you choose your subjects, and what attracts you to them?

I am attracted to the quiet mysteries in the urban fabric, the alleyways of Vũng Tàu or the silhouettes of structures that most people walk past. Murakami speaks about the 'mystique of the mundane,' and I look for that. I choose subjects who feel like they have witnessed something. When I see an architectural detail that carries the weight of memory or time, it becomes the subject. I am looking for the artefact within the architecture.

The carving process in your prints is very deliberate and rhythmic. Can you describe how this labour-intensive practice shapes your creative process?

The carving process is both visceral and meditative. I predominantly work in black and white to emphasise the raw, graphic power of the gouge mark. I choose to hand-burnish every print using a simple wooden baren instead of a mechanical press; this physical commitment allows me to control the pressure and ensures each print carries a tangible trace of human effort. This labour is essential to my philosophy: I don't just carve to make an image; I carve to find the silence that the city drowns out. The 'echo of repetitive motion' becomes a way of re-walking the streets I have seen, processing the noise of the urban environment into a singular, silent artefact of the encounter.

Teddy Bears, Sea and Sky, Phuoc Tinh, linocut, 64 x 45 cm, 2025 © Mark James Murphy

Sea fishing, Vung Tau, linocut, 19.2 x 27.5 cm, 2025 © Mark James Murphy

Your work bridges your Northern English heritage with your current life in Vietnam. How do these different geographies influence the themes and imagery in your prints?

My practice is a visual dialogue between two seemingly disparate worlds. Sunderland gave me my visual vocabulary, the bold, stark lines of industrial heritage, shipyards, and a culture defined by manual labour. Growing up in the North East of England instilled in me a specific industrial work ethic, which I now apply to the vibrant, urban and coastal landscapes of Vietnam. I find a strange comfort in the ubiquity of scaffolding; in Sunderland, it represented the preservation of industrial history, while in Vietnam, it represents the relentless vertical growth of the future. This architecture of change is a recurring motif in my work. Whether it is a shipyard crane in the North East or a bamboo structure in Vũng Tàu, these temporary skeletons reflect the internal scaffolding we build within ourselves as we try to stay upright during the process of cultural assimilation.

These geographies influence my themes by creating a tension between my roots and my current environment. While the subjects are Vietnamese, the 'language' I use to describe them is Northern English: gritty, high-contrast, and unapologetically physical. This bridging allows me to explore cultural assimilation not as a loss of identity, but as a layering of it. I am applying a cold heritage to a hot environment, finding that the stillness I sought in the industrial North is the same stillness I now carve out of a Southeast Asian city.

Memory and stillness are central to your work. How do you translate these abstract ideas into physical prints?

Stillness is not the absence of movement; it’s the presence of attention. I translate memory through layering, not necessarily in colour, but in the density of marks. By focusing on the 'overlooked,' I freeze the velocity of the city. The black ink represents the weight of the physical world, while the carved white spaces represent the silence or the void where memory lives. It turns an abstract feeling into a high-contrast physical reality.

View from Whitby Pier, North Yorkshire, linocut, 19 x 28 cm, 2023 © Mark James Murphy

In the backstreets of Rome, linocut, 25 x 34 cm, 2016 © Mark James Murphy

How have audiences responded to your linocuts, both locally in Southeast Asia and internationally?

In Southeast Asia, people often resonate with the familiar scenes rendered in a medium that feels both traditional and refreshingly raw. Internationally, as seen in my recent New Hampshire exhibition, audiences are drawn to the universal feeling of urban solitude. People tell me they feel a sense of longing or quiet in the work, which proves that the 'Anchor of Attention' works regardless of where the viewer is standing.

What projects are you currently working on, and are there any new directions or themes you’re exploring in your practice?

I am currently moving toward a more monumental and modular linocut practice that seeks to translate the internal experience of cultural assimilation into a physical environment. My upcoming work explores liminality as a metaphor for the immigrant experience, using shadowy, cavernous compositions to mirror the ambiguity of navigating a dual identity in Southeast Asia. I want to move beyond the surface narrative and into the very architecture of the story, creating 'in-between' spaces where my Northern English heritage and Vietnamese life don't just collide, but begin to grow into one another.

Technically, I am developing a modular system where I treat my carved symbols, Vietnamese alleyways, industrial scaffolding, and folk icons, for example, as memory blocks. By printing these fragments in isolation across large-scale black and white fields, I use the physical void of the paper to represent the psychological void of integration. I am particularly interested in how these works can function as physical installations; I want to ask the viewer to inhabit the shadows of these prints, where culture is both lost and found.

Of course, this shift toward the monumental brings new practical challenges. I am currently exploring ways to source paper large enough to support these cavernous fields and seeking the physical space required to print these modular works after the labour-intensive carving of each block is complete. My goal is to eventually create immersive, large-scale environments where the scale of the print matches the scale of the psychological journey it represents.

Figures in the sea, Alley 107-109 Tran Phu, Vung Tau, linocut, 19.2 x 27.5 cm, 2025 © Mark James Murphy

Lastly, looking ahead, what are your artistic goals for the next few years, and what would you like your work to communicate in the future?

Looking ahead, my goal is to continue expanding the language of relief printing to prove it is not merely a traditional craft but a high-level conceptual tool for navigating the modern human experience. Ultimately, I want my work to communicate a sense of re-enchantment. In a world that often feels cold, fast, and purely functional, a state the sociologist Max Weber described as the 'disenchantment' of modern life, I want to remind the viewer that there is a deep, quiet wonder to be found in the overlooked details of our environments. I want to turn the ordinary street into a site of contemplation. By using the 'Anchor of Attention' to slow the viewer down, I hope my prints act as a bridge back to a more soulful, deliberate way of inhabiting the world. My goal is for my work to not just represent a place, but to return the magic to the mundane spaces we move through every day.

Finally, as an artist whose path has been a hybrid of formal theory and self-taught practice, I hope my work communicates that mastery of a medium is ultimately a private negotiation between the individual and the material. You don't need a printing press to find your voice; sometimes, a simple wooden spoon and a commitment to the 'resistance' of the lino are enough to reveal the internal world that Murakami speaks of. I want to encourage others to see the limitations of their environment not as barriers, but as the very things that will give their work its unique, grounded truth.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a curated promotional platform that offers artists the opportunity to articulate their vision and engage with our diverse international readership through insightful, published dialogues. Conducted by Mohamed Benhadj, founder and curator of Al-Tiba9, these interviews spotlight the artists’ creative journeys and introduce their work to the global contemporary art scene.

Through our extensive network of museums, galleries, art professionals, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide, Al-Tiba9 Interviews provides a meaningful stage for artists to expand their reach and strengthen their presence in the international art discourse.