10 Questions with Tamara Novikova

Tamara Novikova is a visual artist and packaging accessories designer based in New York City. Raised between Russian and American culture, she brings a cross-cultural perspective to her practice, blending the structure of design with the intuitiveness of drawing. Her signature use of red and blue ballpoint pens reflects both personal history and her ongoing interest in memory, form, and repetition. Her illustrations move fluidly between fine art and everyday utility, transforming simple materials into expressive, textured surfaces. Novikova’s work has been exhibited in galleries across New York, and she continues to explore the evolving dialogue between commercial design and conceptual art

Tamara Novikova - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Tamara Novikova’s work focuses on how simple materials and everyday objects can open up new ways of seeing. Using red and blue ballpoint pens, she turns a common writing tool into a way of building bold, layered drawings. She often starts with an ordinary object she finds visually interesting, then redraws it through repeated marks until it grows into a large, abstract cluster. Her process is steady and hands-on, letting shapes shift naturally as the ink builds up. Influenced by her design background and early schooling in Russia, Novikova likes working with basic materials because they keep her grounded and connected to the familiar. Through this approach, she shows how something small and simple can become playful, energetic, and surprisingly expressive.

100 PERCENT CHEESE, Ballpoint pen and colored pencil, 46x30.5 cm, 2024 © Tamara Novikova

INTERVIEW

You were raised between Russian and American cultures. How has this dual background shaped the way you see and make art?

Growing up between Russian and American cultures gave me a layered way of seeing. From the Russian side, I absorbed a deep respect for technique, craftsmanship, and the "old world" discipline of learning to really look at something. There's a seriousness and structure to that way of making art that still informs how I approach a drawing, almost like the underlying architecture of my work is rooted in that early training.

In contrast, my American experience exposed me to a more contemporary, experimental way of thinking. It taught me that familiar objects can be reinterpreted, expanded, and abstracted into something new. That sense of openness and reinvention shapes how the drawings ultimately grow.

So in a way, my work mirrors those two influences: the structure and attention to craft feel very Russian, while the larger abstract forms that emerge, the clusters built from still-life objects, carry a more American contemporary spirit. Living between these cultures has made me comfortable combining discipline with curiosity, tradition with play.

What first drew you to use red and blue ballpoint pens as a main tool in your drawings?

I started using ballpoint pens in school in Russia, where they were as standard as the No. 2 pencil is in the U.S. Because I never had intensive academic art training, just two life-drawing classes and a design education, I ended up teaching myself how to draw with whatever was available. The pen became a kind of instructor for me. You can't erase ballpoint ink, so it forced me to own my mistakes, adapt, and build technique through trial, error, and repetition. That challenge shaped the way I draw today.

I also like that the pen lives in both worlds of my life: it's a professional office tool and an artistic tool. It's cheap, small, familiar, and completely unpretentious. There's something honest about building complex, layered images from something so ordinary.

The colour choice also grew naturally out of my environment. Living and working in New York, I kept noticing how much of the city's visual language, signage, transit, and graphics sit in the red/orange and blue palette. Blue ballpoint was always the default, and red/orange became the perfect energetic counterpart. The combination felt both practical and symbolic of the city around me, and it stayed with me.

THE NEW INVASIVE SPIECIES, Ballpoint Pen, 20x28 cm, 2022 © Tamara Novikova

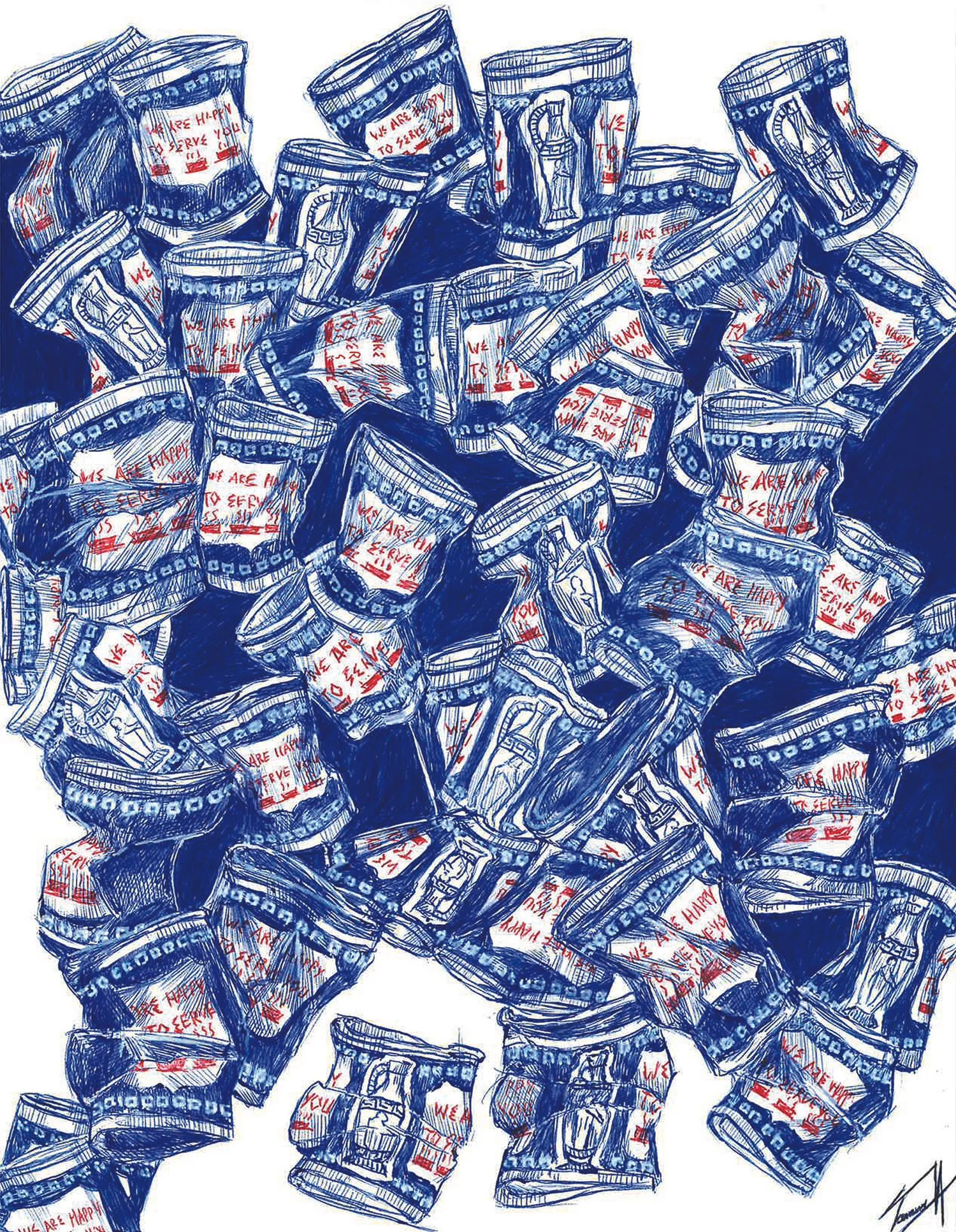

WE WERE HAPPY TO SERVE YOU, Ballpoint Pen, 20x28 cm, 2023 © Tamara Novikova

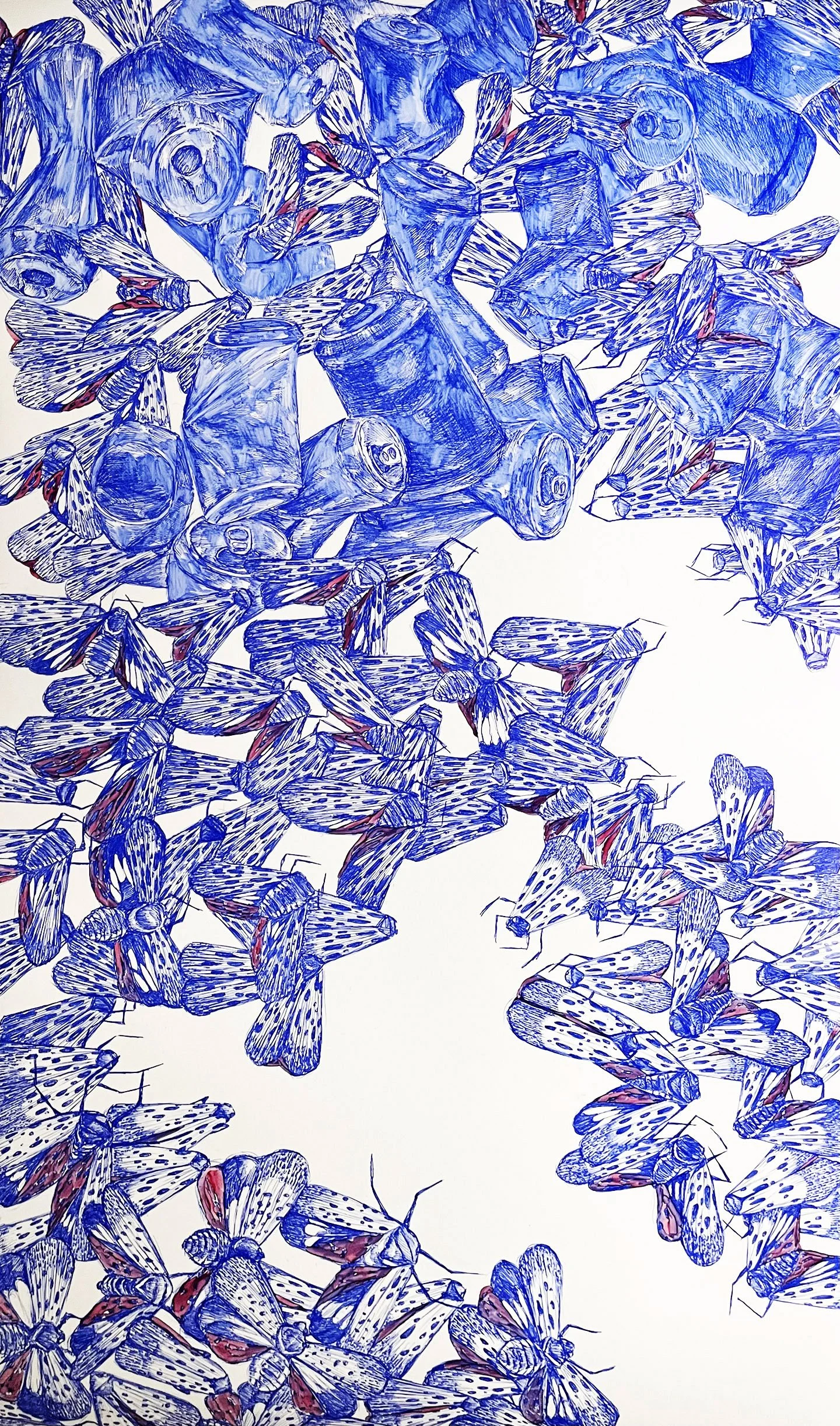

Many of your drawings start from simple, everyday objects. What makes an object interesting enough to become the starting point of a work?

I'm drawn to everyday objects for a mix of visual and psychological reasons. Sometimes the starting point is purely colour. I'll see something that's the perfect blue or a bold red-orange, and I immediately want to translate that into ballpoint ink. Other times it's the texture that grabs me. Honestly, about 70% of the impulse comes from asking myself, "What would this look like in a ballpoint pen? Could I even pull this off?" There's always a challenge in trying to make a simple object feel alive through such a restrictive medium.

There's also an element of repetition that comes naturally to me. I often draw an object, then draw it again next to the first one, as if to say: "Just in case you didn't see it." And then I draw it a third time so the viewer definitely sees it, and eventually a whole cluster, so there's no doubt what they're looking at. I've noticed I speak this way too, repeating myself in conversation to make sure I'm understood. That pattern shows up visually in my work without me consciously planning it; it's just how my brain organises things.

Some pieces begin with a digital collage that I build in Photoshop and then translate using a grid method, and others are drawn completely loosely, letting the cluster form organically. But whether the origin is digital or spontaneous, the object has to spark something with me: curiosity, challenge, colour, and/ or texture.

Can you walk us through your creative process, from choosing an object to building it into a layered composition?

The process usually begins with what initially draws me to an object, often its colour, sometimes its texture, and always the challenge of imagining it in ballpoint pen. From there, the path depends on the piece. Some works start with digital experiments in Photoshop, where I layer, collage, and arrange elements to explore composition before translating it to pen on paper using a grid method. Other works are entirely loosely freehand, letting the object grow organically as I cluster marks and build repetition.

Regardless of the approach, the work develops slowly, mark by mark. I pay attention to rhythm, layering, and the wayclusters interact, allowing the composition to emerge naturally while keeping the original qualities of colour and texture intact. Whether digital or analogue, the goal is the same: to transform familiar objects into something richer, more abstract, and visually engaging.

JUST SOME BOTTLES AND SYRINGES, Ballpoint and marker, 35.5x40.6 cm, 2025 © Tamara Novikova

How does your design background influence the way you approach drawing as a fine art practice?

My design training and professional experience have deeply shaped how I approach drawing. In school, I focused mainly on fashion and designing objects, which meant I was dealing with three-dimensional forms and thinking about how they function in the real world. After college, my career initially involved high-end, bespoke projects, fabric treatments, 3D printing, beading, and intricate craftwork for runway shows, galas, and special events. Later, I shifted into mass-market design for accessories, where the focus was less on luxury craftsmanship and more on cost, production constraints, and competing in a crowded marketplace. Eventually, I moved into packaging graphics, where I found a lot more creative freedom: sketching, illustrating, and thinking about layouts and presentations of both products and their packaging.

Across all of these experiences, design taught me to work within parameters, whether structural, material, or commercial. That discipline translates directly into my fine art practice, particularly in the way I handle pattern, repetition, and the structure of my compositions. At the same time, my fine art work offers an even greater freedom; I can illustrate and explore anything I imagine, but the sensibility of organisation, layering, and visual patterning still carries over from my design background. In essence, both worlds rely on building visual systems, whether for products, packaging, or clusters of drawn objects.

Your works grow through repetition and accumulation of marks. What role does patience or rhythm play in your practice?

Patience and rhythm play different roles at different levels in my work. The act of creating can be quite staggered for me; I often have to hover over my desk for long stretches, then step away, walk around, and come back to reassess and redraw. My mind easily wanders to other ideas, so keeping focus requires effort. If I were to compare the rhythm of my process to music, it would definitely be jazz: notes scattered, improvisational, and sometimes unpredictable.

That said, rhythm within the composition itself is something I pay close attention to. Even when clustering objects seemingly randomly or embracing asymmetry, there has to be a visual cohesion. Each object is considered in relation to the others, so the eye can move through the work naturally, and the repetition and accumulation of marks feel deliberate rather than chaotic. Patience comes from allowing this process to unfold over time, letting the composition settle into a balance between spontaneity and structure.

INVASIVE SPECIES, Ballpoint and marker, 45.7x73.5 cm, 2023 © Tamara Novikova

SALMON ROE ON WHITE BREAD, Ballpoint and marker, 45.7x37 cm, 2024 © Tamara Novikova

Ballpoint pens are ordinary and accessible materials. Why is it important for you to work with something so familiar and common?

Working with ballpoint pens keeps my practice grounded and approachable. They're everyday objects, familiar and unpretentious, and that simplicity mirrors the objects I draw, ordinary things that often go unnoticed. Because they are cheap, portable, and immediate, I can focus entirely on the act of drawing: layering, building texture, and exploring repetition without being distracted by tools or materials.

There's also a psychological dimension: using such a familiar tool demands presence and attention, since every mark is permanent. The pen allows me to embrace mistakes, to experiment, and to explore composition and pattern in a way that feels both intuitive and disciplined. In short, the ordinary nature of the pen makes extraordinary outcomes possible.

Your pieces often balance structure and playfulness. How do you keep this tension alive while you work?

Playfulness in my work often comes from the objects themselves and how I choose to combine them. I like creating smallcontradictions, visually, conceptually, or even through the titles I give the pieces. Sometimes it's humorous or a little sarcastic. For example, one work clusters goldfish snacks and Cheez-It snacks together, which is 100% playful and exaggerated, poking fun at processed perfection and consumer culture.

At the same time, there's always a structure underlying the work. Even when objects are arranged in odd or contradictory combinations, I pay attention to composition, repetition, and visual balance. The tension between structure and play emerges naturally: the serious, deliberate act of building clusters contrasts with the humorous or unexpected relationships among the objects themselves. That dynamic keeps the work alive and engaging.

You have exhibited in New York galleries. What did you learn about the contemporary art market from these experiences?

Since starting my new portfolio in 2022, I've had just a couple of years of exposure to the New York gallery scene, mainly through independent juried group shows. I found that my work is able to fit into a variety of curatorial themes, which may have been beginner's luck, but it also highlighted something consistent: curators and judges value cohesion in a body of work.

At the same time, I've realised that the fine art world is still a business. It would be naïve to think that galleries, collectors, or the market respond solely to an artist's personal expression. If you want people to be interested in and ultimately purchase your work, you have to understand it as a commodity. In today's world, being an artist often means being a businessperson as well.

For me, this awareness reinforced the importance of having a clear theme. Once I settled on the ideas I wanted to explore, I focused on sticking with them consistently. Cohesion allows a body of work to grow, resonate, and be memorable, and it's ultimately what helps your work reach a wider audience.

Tamara Novikova’s studio

Lastly, looking ahead, where do you see your work heading next? Are you working on any new project or series?

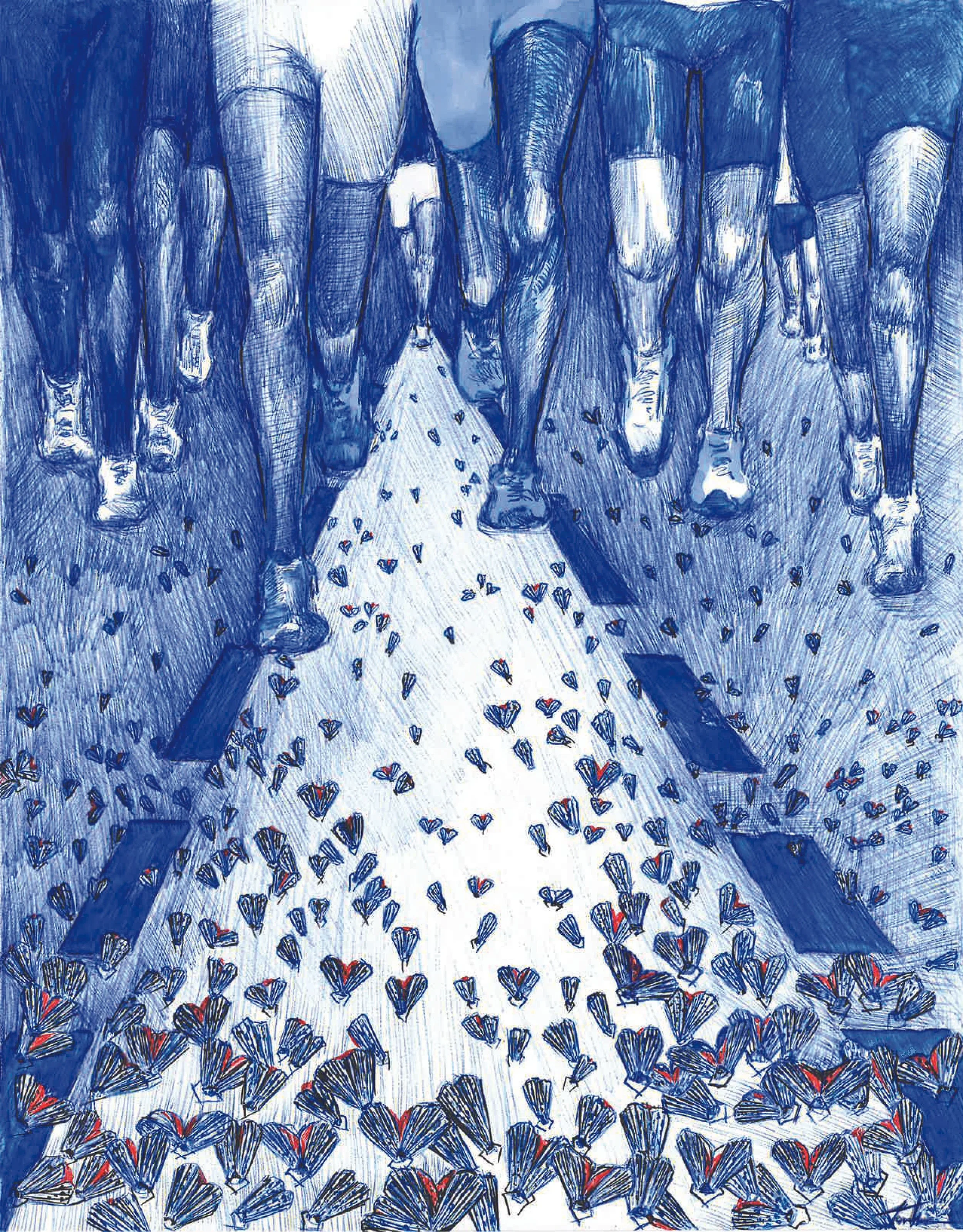

Lately, my work has taken a turn toward athletes' legs. A few months ago, I joined the Upper East Side running club in Manhattan, and suddenly, I was seeing legs as fascinating objects in their own right. I've been running long distances since 2013, but training for the Berlin Marathon and being part of a group has given me a new perspective and a new set of muses.

Drawing in ballpoint pen is a slow, meticulous practice that demands patience and focus, and I've realised that long-distance running trains the same mental muscles. Both require staying present, steady, and not rushing, whether it's a marathon or building a cluster of tiny marks.

Suppose Degas, for example, drew dancers to reveal the imperfections and realism behind the stage. In that case, I'm more interested in the perfection I see in the limbs of my fellow runners, the way legs are sculpted through motion and repetition. Studying them closely is a mix of admiration, observation, and, I'll admit, a little playful obsession. It's both meditative and inspiring, and I'm excited to see how this series evolves as I continue exploring form, motion, and detail.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.