10 Questions with Yiqi Zhao

Yiqi Zhao (Edie) is a visual artist and illustrator whose surrealist practice interrogates themes of identity, societal constraints, and resilience through a fusion of meticulous craftsmanship and symbolic storytelling. Holding a BFA in Graphic Design from the School of Visual Arts, New York (2022) and an MA in Children’s Literature and Book Illustration from Goldsmiths, University of London (2023), her work bridges cultural critique and emotional introspection.

Zhao’s art evolved from realism to surrealism, driven by her experiences as a woman navigating societal expectations and cultural traditions. Her Limited Strength Series—exhibited at The Holy Art Gallery, Bushwick Gallery, and London Contemporary (2025)—uses ballpoint pen and ink to subvert patriarchal norms, reimagining the nude form as a site of defiance. Pieces like Safe House or Jail? and Escape merge Chinese motifs with surreal landscapes, exploring vulnerability as resistance.

Her work has been recognised with awards including the Gold Key at the Milwaukee Art Museum (2017) and featured in exhibitions across London and New York, such as Metamorphosis (34 Gallery) and Sensuous Bodies (Fox Yard Studio). Through surrealism, Zhao invites viewers to question societal limitations and embrace the unknown, transforming personal introspection into universal dialogue.

Currently based in London, she continues to expand her practice, blending traditional techniques with digital innovation to amplify underrepresented narratives.

Yiqi Zhao - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Yiqi Zhao’s artistic journey began with realism, rooted in capturing observed realities. Over time, her practice evolved into surrealism, blending emotion, lived experience, and imagination to craft worlds that transcend conventional boundaries. Her work interrogates themes of freedom, identity, and societal constraints, informed by her navigation of cultural traditions and gendered expectations as a woman.

Zhao’s surreal, dreamlike landscapes challenge oppressive narratives, transforming personal introspection into universal dialogue. Through meticulous techniques in ballpoint pen, ink, and watercolour, she reimagines cultural symbols—hair as both lifeline and shackle, cranes as enforcers of silence—to critique patriarchal structures and celebrate resilience. Her Limited Strength Series(2025), exhibited internationally, dissects the duality of strength: inherited, imposed, and reclaimed.

Zhao’s art invites viewers to question societal limitations, embrace ambiguity, and find power in vulnerability. Her practice is both refuge and provocation—an ongoing exploration of self and the collective human experience.

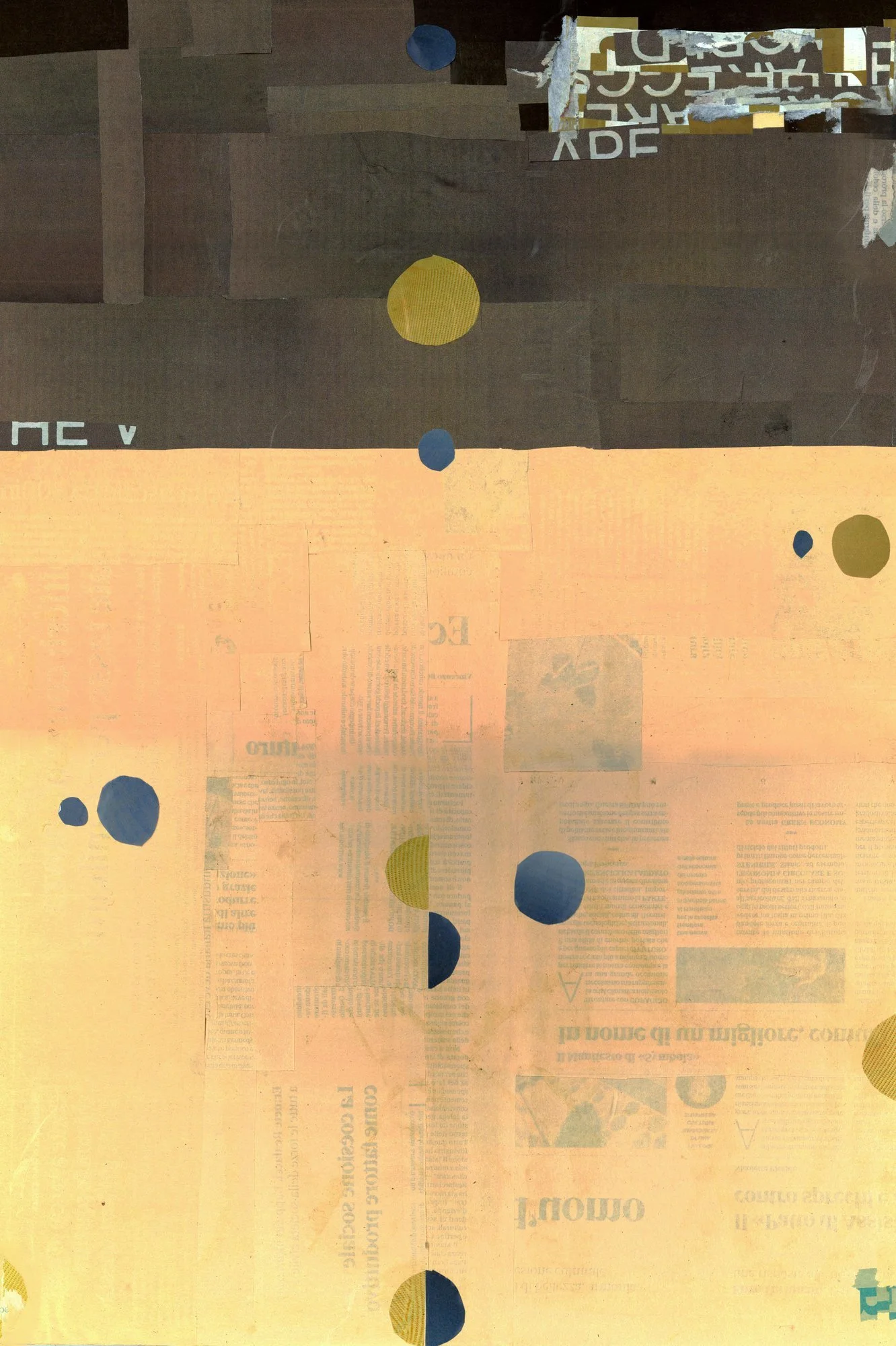

Lost&found, collage, 19.5x19.5 cm, 2022 © Yiqi Zhao

INTERVIEW

Please tell us a bit about yourself. Who are you, and how did you become interested in art?

I'm Yiqi (Edie) Zhao, a multidisciplinary artist navigating the intersections of cultural identity, displacement, and resilience. My artistic journey began in a Chinese household steeped in textiles and craftsmanship, where I developed an early sensitivity to colour and form. Though I initially studied graphic design at the School of Visual Arts in New York, a pivotal mentorship during my BFA years redirected me toward fine art. My work now merges Eastern symbolism with Western surrealism, driven by a need to translate personal and collective fractures into visual poetry.

Your artistic journey began with realism before evolving into surrealism. What prompted this transition, and how did it shape your approach to storytelling?

Realism taught me to see, but surrealism taught me to speak. Early on, I aimed to replicate reality faithfully, but I soon realised art's power lies not in mirroring the world but in refracting it. The shift began during my migration from China to the U.S. at 15—a disorienting experience that shattered my sense of stability. Surrealism became a language to articulate the unspeakable: the weight of cultural dislocation, the paradox of visibility and erasure. In works like Vagabondage, I replaced literal representation with metaphorical landscapes, where umbrellas morph into fragile shelters, and bodies dissolve into the rain. Storytelling became less about narrative and more about emotional archaeology.

How does your background in graphic design and children's book illustration influence your practice's narrative and aesthetic qualities?

Graphic design instilled in me a rigour for composition and visual hierarchy, which surfaces in the meticulous crosshatching of my Limited Strength series. Meanwhile, Children's book illustration honed my ability to distil complex emotions into symbolic gestures—think of how a single tear in a storybook can convey grief without words. This duality manifests in works like Lost and Found, where collage layers balance structural precision with whimsical abstraction. Even in surrealism, there's an underlying grid, a ghost of my design training holding chaos at bay.

You often incorporate Chinese motifs and symbolism in your surreal compositions. How do cultural heritage and identity shape your visual language?

Cultural symbols are my alphabet and my ammunition. In Shut Up, I subvert the crane—a traditional emblem of wisdom—into a skeletal enforcer pecking at a woman's throat. Hair, once a marker of feminine virtue, becomes barbed wire or roots in my pieces. These motifs are palimpsests: I scrape away their patriarchal patina to expose raw, rebellious cores. My visual language isn't about preserving heritage, but interrogating it, turning heirlooms into mirrors that reflect bothbeauty and cracks.

Lost&found, collage, 19.5x19.5 cm, 2022 © Yiqi Zhao

Lost&found, collage, 19.5x19.5 cm, 2022 © Yiqi Zhao

The Limited Strength Series powerfully confronts patriarchal norms. Can you share the genesis of this series and what it means to you personally?

Limited Strength was born from a suffocating moment: family members critiquing my life choices, reducing my ambitions to "too ambitious for a woman." I channelled that frustration into ballpoint ink—a medium as unyielding as the expectations imposed on women. The series reimagines the nude female form not as a passive object, but as a battleground. In Escape, a figure ascends a vortex of her own hair, battling headless adversaries. For me, this series is a manifesto: strength isn't the absence of struggle, but the audacity to struggle visibly.

Your medium, ballpoint pen and ink, requires great precision and patience. What draws you to these traditional tools, especially in an era of digital art?

Ballpoint ink is democracy in a pen—cheap, accessible, and unforgiving. Its permanence mirrors societal judgments: once a mark is made, it can't be undone. In Limited Strength, this rigidity becomes a metaphor for the inflexibility of gender roles. Digital tools, while efficient, lack the tactile resistance I crave. When I press ink into paper, it's a corporeal act—a tiny rebellion against the ephemeral swipe of a screen.

You describe your art as both a refuge and a provocation. How do you balance introspection with societal critique in your creative process?

The studio is my confessional; the gallery, my pulpit. Vagabondage began as a private catharsis—a way to process loneliness—but its glowing umbrella resonated universally, becoming a symbol for migrants worldwide. I start with personal wounds, then suture them to collective ones. Even the most introspective piece, like Anchor (a hyper-detailed study of my ankle), whispers about the burden of bearing weight silently. To me, art is a bridge between the "I" and the "we."

Escape, ball-point pen, 29.7x42 cm, 2022 © Yiqi Zhao

Incomplete, ballpoint pen, 14.8x21 cm, 2022 © Yiqi Zhao

Safe house or jail, ball-point pen, 14.8x21 cm, 2022 © Yiqi Zhao

Surrealism in your work feels deeply personal yet universally resonant. What role do dreams or the subconscious play in your visual storytelling?

Dreams are my collaborators. Lost and Found's radar operators with giant ears emerged from a recurring nightmare about being heard but not understood. I keep a journal by my bed, scribbling half-remembered symbols upon waking. These fragments—a hairline crack in a teacup, a door floating in fog—become compositional anchors. Surrealism isn't escapism; it's truth-telling in disguise. By warping reality, I bypass the censors of logic and touch raw nerves.

As a woman navigating societal and cultural expectations, how has your art helped you reclaim agency and open space for dialogue?

Art is my exoskeleton. Growing up, I internalised the notion that "good women" should be small and silent. Through Shut Up and Limited Strength, I've weaponised that silence. By depicting hair as both a noose and a lifeline, I reclaim what patriarchal norms reduced to ornamentation. Exhibitions become safe houses where viewers, especially women, approach me with stories of their own constraints. My art doesn't just voice my resistance; it amplifies theirs.

How do you envision your practice evolving, particularly as you experiment more with digital techniques and underrepresented narratives?

I see digital tools as new dialects, not replacements. Recently, I've been scanning ballpoint drawings and animating their textures—imagine the barbed-wire hair in Shut Up unravelling into digital glitches. The goal isn't to abandon tradition but to let it hybridise, much like identity itself.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.