10 Questions with Baron Hill

Baron Hill is a young abstract artist based in Davie, Florida, whose work focuses on themes of emotion and self-reflection, often expressed through drawing.

Influenced by abstract icons like Jean-Michel Basquiat and inspired by ambient, breakcore, and electronic music, Baron uses art to dissect the roots of difficult emotions, sadness, anger, and guilt, capturing them in mostly detailed, intricate dark lines,swirls, arcs, and colors that emphasize their depth and intensity.

Entirely self-taught, Baron Hill currently attends Sagemont Preparatory School in Weston, Florida, and continues to refine his medium, with plans to pursue a growing range of artistic opportunities and exhibit their work in more galleries.

Baron Hill - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Baron has spent a lot of time in his own head. Whether it’s stress, overthinking, or lying awake at night with anxiety, he’s grown used to examining his mind and watching everything inside it unfold. Anger built up from small moments. Sadness layered over minor annoyances. Even when the causes are small, they tend to hit all at once. And when they do, he gets lost in the details as the flood rushes in. That’s what Baron Hill’s work represents.

He aims to express the feeling of being stuck inside your mind, where emotions, thoughts, and the weight of past experiences tangle together into something too dense to unwind. They don’t arrive one at a time; they blur into a mass that’s hard to confront and even harder to understand. Each line he draws is an experience, a thought, or a memory pulled from the dark. But these pieces aren’t meant to be hopeless. Even when they reflect deeply personal emotions, they aren’t about giving in; they’re about dissecting, understanding, and ultimately growing.

As he gets older, facing new responsibilities, stress, and sometimes destructive ways of coping, his drawings become both a mirror and a lifeline. Even when they seem pointless or chaotic, they’re his answer to a constantly questioning mind. They’re also something he gives back: a map for anyone else overwhelmed by their own inner chaos.

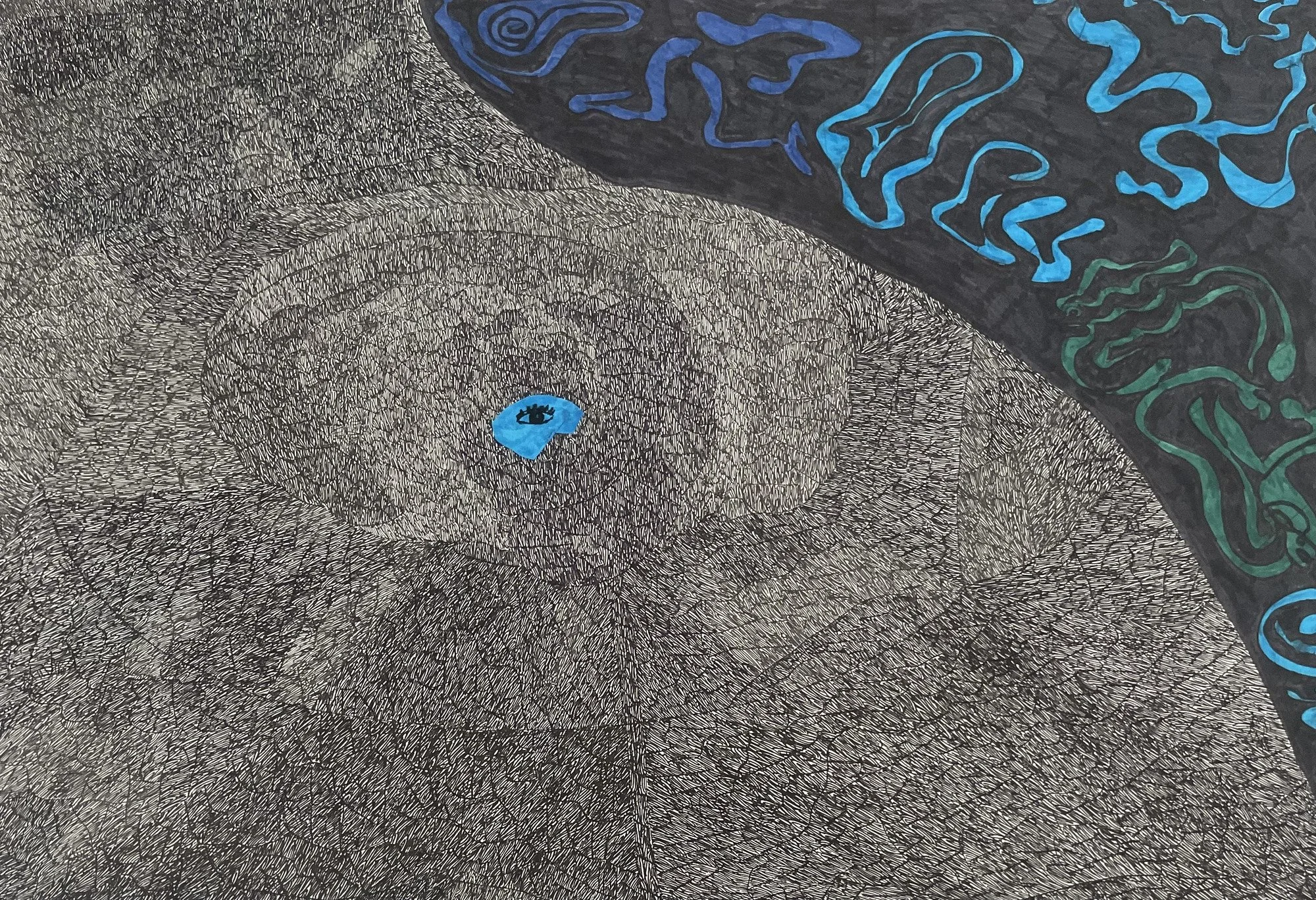

Void, Markers, 18x24 in, 2025 © Baron Hill

INTERVIEW

First of all, can you tell us a bit about yourself and how drawing became such an important part of your life?

Well, if you needed to know something about me, first off, it’s that I’ve always had difficulty expressing myself. As a kid, I had a speech impediment, which led me to speech therapy just to communicate at the same level as my classmates. Even now, I still struggle to express my thoughts and opinions unless I take a long time to gather and organize them, and I often have difficulty communicating my own feelings, desires, and emotions.

Drawing, however, came into my life the way I imagine it does for many people: in a sketchbook, surrounded by crayons and markers. Except for me, that love never left. I kept experimenting, using more and more mediums until I found one that could keep up with the anxious demands of my mind while drawing. Over time, it became something much deeper than that.

Struggling to communicate like my peers, missing social cues, and dealing with similar challenges left me constantly overthinking. I often felt judged and labeled as a “weirdo,” so to speak. But I found the strength I wanted in art. Being able to draw the way I do, and having people not just understand it, but genuinely love it, gives me a sense of joy that very few things can match.

Your work often reflects being “stuck inside your own head.” When did you first start turning these feelings into images?

While I have been using this style for about three years now, I began using my art as a vehicle for my feelings as I got older. What I mean by that is, personally, I used to think that many of the complicated emotions I started to feel, like anger, sadness, and anxiety, were linear feelings that meant only one thing.

For example, I have social anxiety and spent a lot of time trying to dissect what other people meant through their actions: “Why didn’t they respond to me?” “Why aren’t they contributing to the conversation?” All the while, I assumed their feelings (and mine included) were linear, which only amplified my anxiety.

In reality, conversations and, in tandem, social anxiety were far more complex than I thought. They involved many unspoken rules and norms that I didn’t pick up on. Because of situations like this, I realized I was never going to understand how emotions worked, at least not in the way I had been handling my social anxiety. That’s when I took my then-developing style and transformed it to best capture the ever-changing parts of emotion.

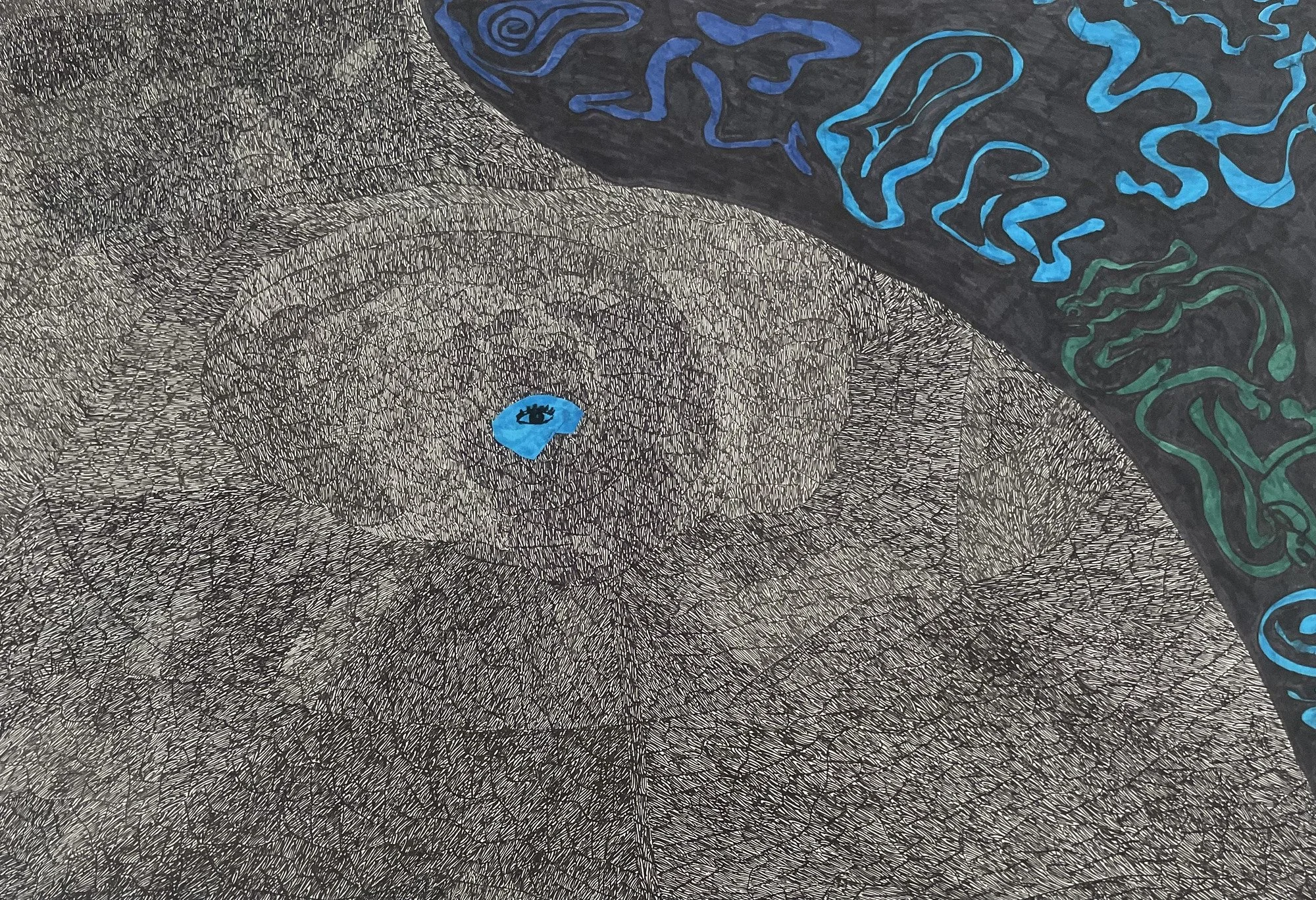

Blow out, Markers, 8x10.5 in, 2025 © Baron Hill

Borderline, Markers, 18x24 in, 2025 © Baron Hill

Drawing seems to be a way for you to process emotions. What usually triggers the start of a new piece?

Usually, I like to start a new piece whenever a certain emotion is strongest at that moment. For example, I’ve had long periods of self-doubt and loathing. Whenever those periods arise, that’s when I take to the pen and start a new piece. Pieces like these can range from exploring why I feel self-loathing to expressing the anger itself and its complicated chaos.

You’re completely self-taught. What has that journey been like for you so far? And what has learning on your own taught you about your process?

The journey so far has had its ups and downs. While it has made me proud of what I can do as an artist, it has also been more challenging than if I had a teacher to guide me. For most of my artistic career, I have focused on honing my ability to draw static and lines, developing it to a point where I can now easily experiment with and intentionally shape those lines into new forms.

The issue is that, because I didn’t have a mentor to guide me or structure how I should practice specific artistic skills, I haven’t fully developed my realism and technical abilities. This means I struggle to draw things that people my age are often expected to handle with the same amount of experience, such as faces, hands, poses, and similar subjects. Overall, this has made me feel behind compared to more advanced peers in the past.

However, it hasn’t been entirely negative. By mastering my craft through intricate patterns and static, I feel proud of what I’ve created. It feels personal, something that reflects who I am as both a person and an artist, and it’s also what sets me apart from my peers.

What I’ve taken from this is that I don’t like to feel restrained, not by a set standard of what art should be, not by a timeline of skills every young artist is expected to have, but guided instead by my own desire and what I want to share with the world the moment I pick up my pen.

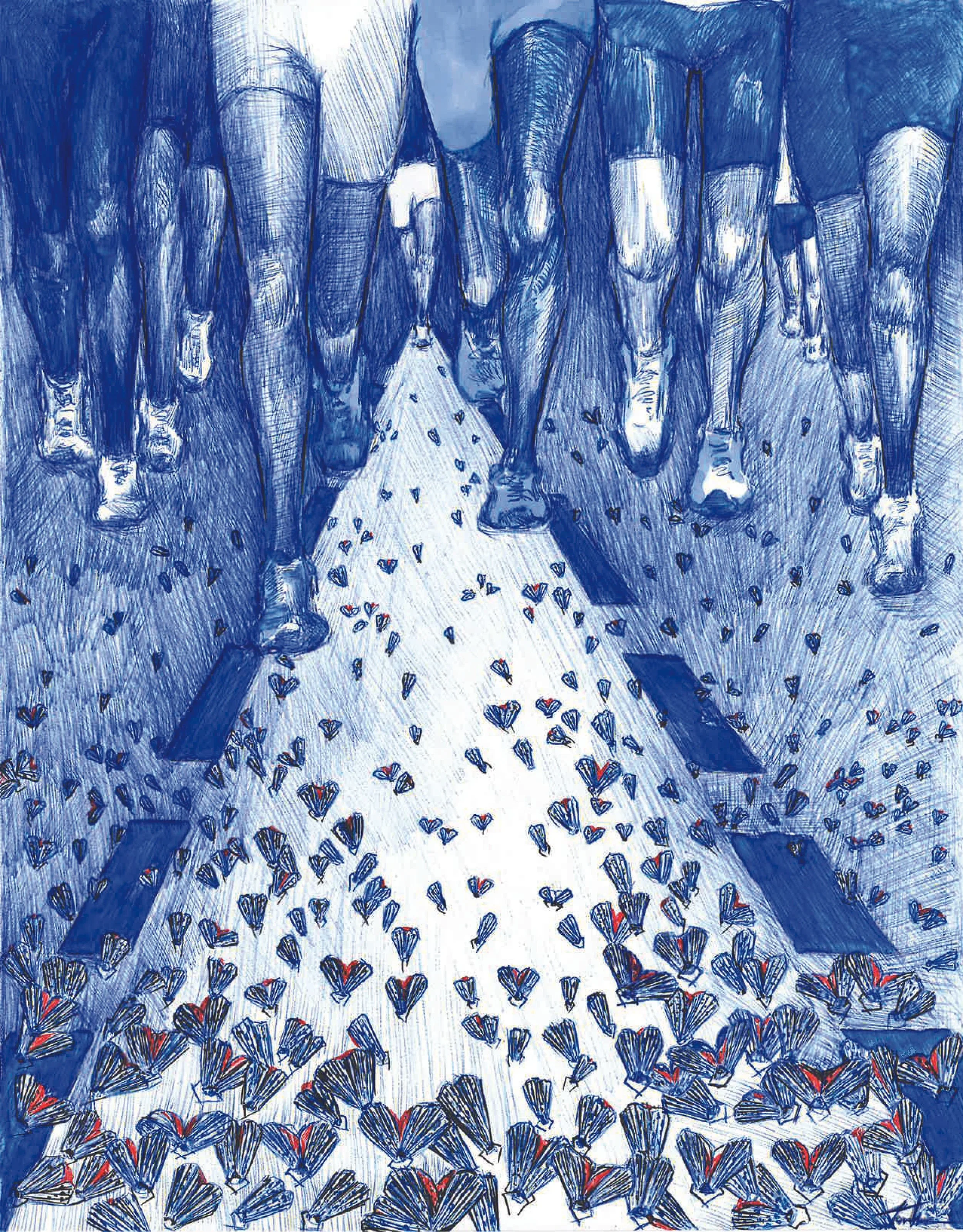

It’s Okay…, Markers, 18x24 in, 2025 © Baron Hill

You work mainly with dense lines, swirls, and dark forms. How did this visual language develop over time?

Now that I think about it, it’s kind of funny how my visual language has developed over time. I used to be a much more energetic and lively person, creating colorful, childlike drawings where lines and doodles sprawled across the page, letting my creativity take control. As I got older, though, my style shifted. Booming colors were replaced by black pen strokes, and pages that once felt full of life and energy became closely knit with just… lines.

As I continued to grow older and started dealing with darker feelings, self-doubt, hatred, overthinking, and anxiety, the lines became more complicated. They began to move, and the once happy-looking pages took on a more serious tone. However, at this point in my life, that has changed. I’m starting to experiment much more now, using more color and trying to reintroduce elements of my old style while also bringing that sense of life back. It’s funny, really, especially considering I’ve just started therapy, which seems to correlate with this shift.

Even though your work comes from difficult emotions, it doesn’t feel hopeless. What does drawing help you understand or release?

Before I start with what exactly my work helps release, I want to add to the idea that my work does not feel hopeless. It doesn’t feel hopeless because that has never been my intention. My work is not meant to show how scary emotions can be, but rather to express them in a way that makes me feel free and explains them clearly, so they don’t scare others who struggle to understand them, as I do. They simply are complicated. And complicated things shouldn’t be feared; they need to be understood. That is something I have been grappling with for a long time.

I used to restrict emotions that made me uncomfortable, or even just a little weird, believing they were bad or shouldn’t be expressed out loud. Then I realized that was stupid. Instead of protecting myself, I was hurting myself by stripping away the things that make us human: the good, the bad, and the ugly. I convinced myself that something was wrong with me and with how I felt.

My art isn’t hopeless because it rejects the ideas I once held about emotions, even the negative ones. It is about releasing and understanding what I used to try to forget, because those emotions, whether I liked them or not, are what made life worth living.

Haggstrom, Markers, 8x10.5 in, 2025 © Baron Hill

Heartbeat, Heartbreak, Markers, 8x10.5 in, 2025 © Baron Hill

Your pieces are very personal, but many people relate to them. How do you feel when others connect with your work?

Ecstatic, mainly because, at first glance, my art isn’t easy to connect with. At least, that’s how I feel. I think it’s because people expect more out of art in general; they want something other than something static to represent emotion. That makes sense. People want a visual conversation with a piece, and I respect that. It has pushed me to experiment with how I convey emotion in my work.

This process becomes especially clear when I show my work to people who aren’t into abstract art, like some of my friends. I’ve gotten critiques such as, “Oh, it’s just scribbles,” or “Isn’t that a waste of time?” or I’m simply told it’s bad without any actual notes for improvement.

But when someone tells me they connect with my work, or even better, says, “This is a good representation of X, Y, and Z,” I don’t just feel happy, I feel proud. I feel proud because, through my art and my process, I’m able to teach and help others understand complicated emotions. That gives me the strength to keep going. It shows me that it is possible to help others in the way I’m trying to, and that there are many more people who could benefit from my work as well.

You’ve mentioned artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat as influences. What do you take from his work into your own practice?

A lot of Basquiat’s work, from what I’ve taken from it over the years, has an innate ability to freely experiment and play with different elements. The way he incorporates numbers and letters, anatomy, and faces, he’s used all of it to create incredible pieces of work.

Going back to a previous question, my own work used to be very constricted: pages filled with crude lines and arcs drawn in pencil that didn’t fully enhance the meaning of the piece for the viewer. However, after looking at Basquiat’s work, I believe he was one of the biggest reasons I began branching out in my craft. Adding more color, implementing more anatomy, using fewer technical lines and arcs, and no longer completely filling the page with my static have all come from Basquiat’s tendency to innovate and think outside the box.

Waves, Markers, 8x10.5 in, 2025 © Baron Hill

What are your goals for the future, and how would you like your work to evolve or be seen in new spaces?

My biggest focus is that I want to try to implement more technical skills into my work. I mean things like hands, faces, shadows, the whole nine yards, but used in a way that makes me the most comfortable. What I mean by that is I don’t want to be drawing full anatomical studies with precise proportions and realistic measurements. As I’ve said before, that feeling of restriction isn’t what I want when drawing. Instead, I want my realism to be messy, have slight errors, but still portray a person with human attributes. While some might criticize that as being ridiculous, humans in and of themselves are imperfect. Not every blemish is void of oil underneath, not every iris is smooth and colorful. Even if I don’t want to take the same route my classmates are taking with technical skill, the way I want to learn is special and something I’m fine with. As for the spaces I want my work to be seen in, I want to focus more on monetizing my work in the future. Seeing how people are able to understand and connect with my work, I believe this is more possible than ever. I want to go to school to earn a degree in both business and art so I can make a living in art in a way that cuts through potential competition while still emphasizing the emotional aspect.

And lastly, what are your biggest goals for 2026? What would you like to achieve this year?

There are two main goals I want to focus on this year so far. They are: Reach 1,000 followers on my Instagram page. I am currently at 490 and gained around 200 followers from a single video last year. Because of this, I believe that if I draw and post more consistently, I will be able to reach my goal by the end of the year. Start making prints of my work. I have already been asked, “Do you sell prints?” At this point in my career, as I begin to gain more recognition for my work, I believe now is the best time to start a shop where I can easily sell my pieces.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.