10 Questions with Yezi Lou

Al-Tiba9 Art Magazine ISSUE18 | Featured Artist

Yezi Lou (b.1997) earned her BFA from the School of Visual Arts and is currently an MFA candidate at UCLA. Lou challenges classical oil painting through subtle shifts in palette and bold subject choices. With sensitivity, her paintings reinterpret everyday life's clarity into ambiguous forms. Her works evoke a tangible presence yet deliberately cultivate distance and absence. Lou's formal strength lies in her use of redacted narratives. Recent solo exhibitions: Silent Observers, The Scholart Selection, San Gabriel, US, 2024; Under the Surface, A/W Space, Nanjing, CN, 2024; Corner of My Eye, Xela Institute of Art, Long Beach, US, 2024. Recent group exhibitions: Outpost, Gene Gallery, Shanghai, CN, 2024; All Things Equal, Good Mother Gallery, LA, US, 2024; Venice Family Clinic Benefit Exhibition, Venice, US, 2024; The Realm of Possibilities, Sasse Museum, Pomona, US, 2024; Reverie retrouvée, Unveil Gallery, Irvine, US, 2023; MFA's of LA, Good Mother Gallery, LA, US, 2023.

Yezi Lou - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Yezi Lou's practice revolves around "objects" as entry points into explorations of belonging, nostalgia, and alienation. Her paintings feature mundane objects stripped of original economic value, reflecting shifting identities and interactions beyond traditional social frameworks. Lou's fascination with consumer goods stems from her upbringing during China's rapid transition from socialism to market economy. Growing up in Wenzhou—a city known for its entrepreneurial spirit—she saw consumer items symbolize status and shape social dynamics. Childhood exposure to mass-produced toys, stationery, and decorations reemerges in her art as symbols of memory. For Lou, nostalgia is a political act of remembering, mediating between collective and individual memories. Her objects evoke nostalgia not for a homeland, but for lost possibilities and unfulfilled aspirations, embodying promises that never materialized.

Untitled (Green Caterpillar), Oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches, 2025 © Yezi Lou

AL-TIBA9 ART MAGAZINE ISSUE18

INTERVIEW

Starting from the basics, when did you first realise you wanted to be an artist? And how did you develop into the artist you are today?

Unlike many artists I know, I came to art relatively late. I didn't fully commit to becoming an artist until I decided to pursue graduate studies in art. It took me a long time to begin understanding who I am, and while that question remains open-ended, the ongoing process of questioning, observing, and self-reflecting continues to drive my artistic practice. Becoming an artist, for me, has not been about arriving at a fixed identity but embracing uncertainty as a generative space.

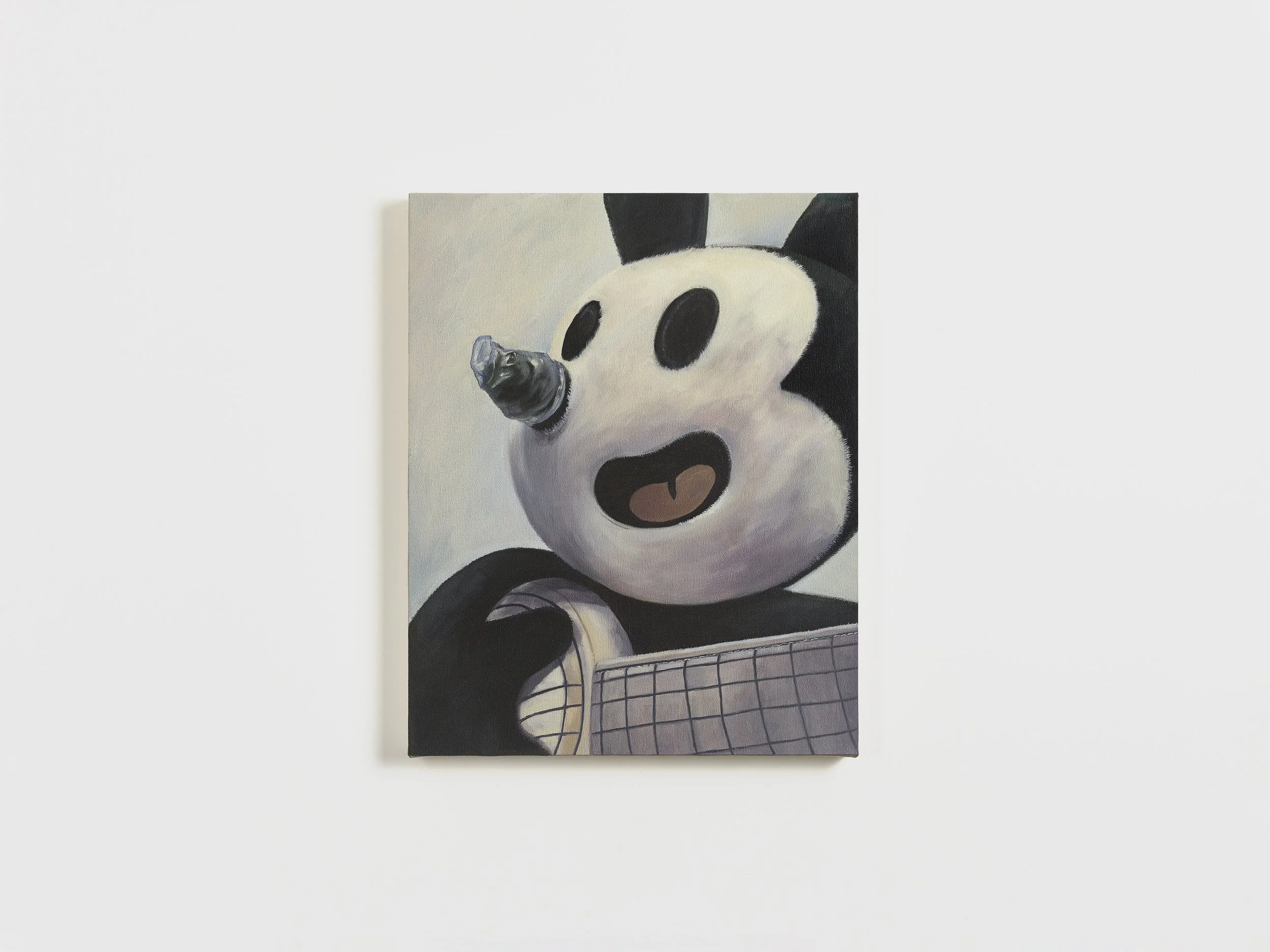

What Have You Done to Oswald, Oil on Canvas, 16x20 in, 2023 © Yezi Lou

You studied at the School of Visual Arts in New York and are now completing your MFA at UCLA. How have these two cities, and their art communities, shaped your development as a painter?

The purpose and pursuit in each city and each school have been very different. At SVA, I began by training as an illustrator, where I received rigorous instruction in precise image-making and clear storytelling. My foundational understanding of art was built on a direct, pictorial approach. Over time, however, I found myself increasingly drawn to traditional mediums over efficient digital tools, and to the playfulness of ambiguity rather than clarity. Life in New York was structured and disciplined, which sharpened my technical skills—I learned primarily through the institution. In contrast, my time in Los Angeles has been more open. The environment has given me the freedom to experiment, and I've learned just as much from my peers as from formal instruction. Both cities have shaped me, each in their own way, through a certain urgency that pushed me to grow at the right moments.

Oil painting has deep traditions, but your work plays with and challenges them. What keeps you working in this medium?

It is undeniable that the power of traditional media, such as oil painting, has been diminished by technological advancements. As images are rapidly generated and disseminated through digital tools, further accelerated by artificial intelligence's ability to simulate "reality", I am always intrigued by how painting's role has evolved across different eras of society. I came as a meticulous painter, obsessed with capturing life with precision, working from photo references to achieve a perfect likeness. However, over time, I've grown more interested in subjectivity—in the space where mistakes, ambiguity, and unpredictability are not flaws but essential qualities. Rather than claiming that figurative art represents reality, I now see it as constructing an illusion: an image deliberately crafted to convince us of its truth. That tension between fabrication and belief keeps me engaged with oil painting as a medium—it resists obsolescence by inviting deeper questions.

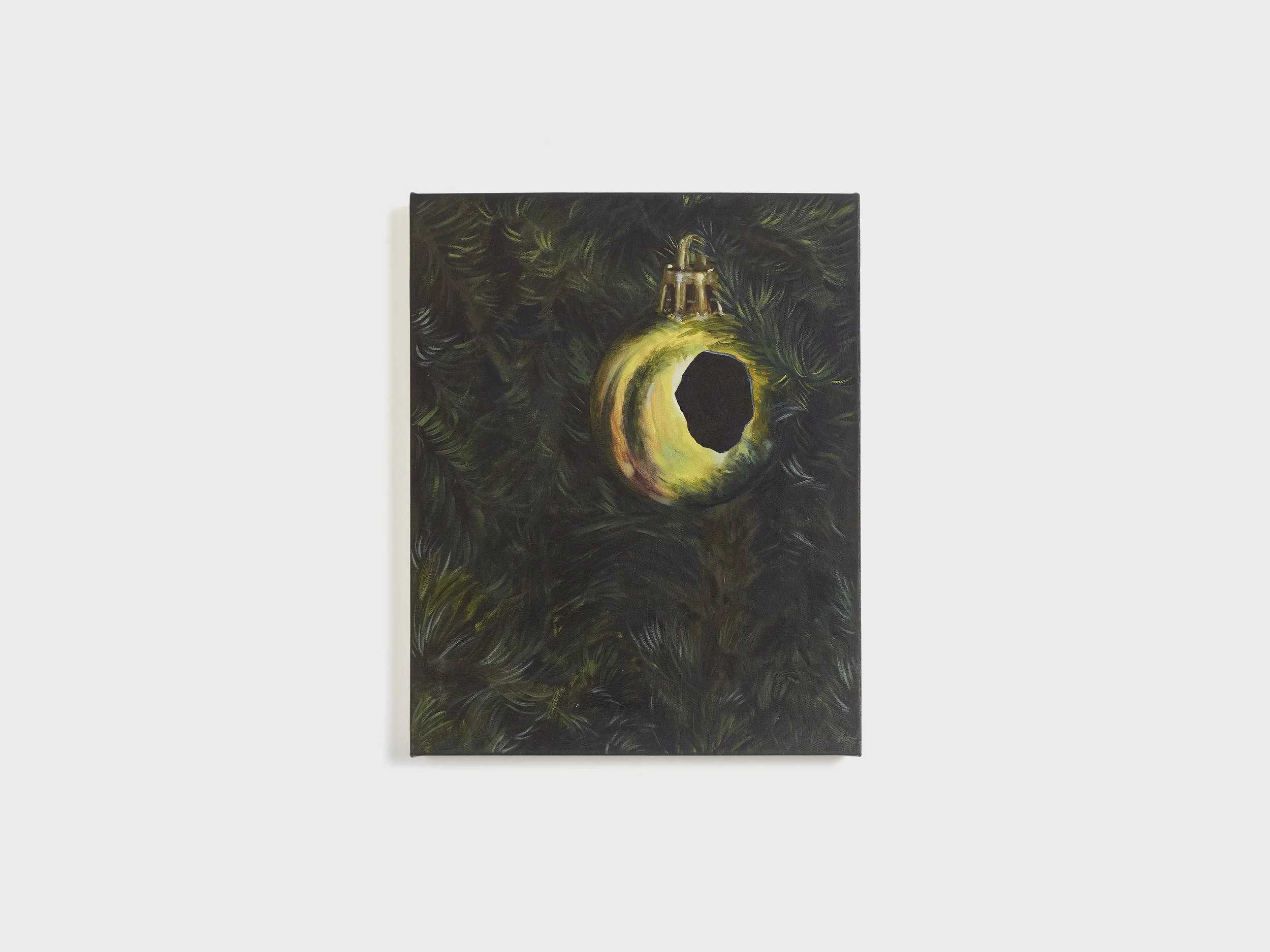

Holiday Season Hangover, Oil on Canvas, 16x20 in, 2024 © Yezi Lou

The Upper Part of The Field Was Full of Rabbit Holes, Oil on Canvas, 30x40 in, 2024 © Yezi Lou

Your use of redacted narratives and ambiguous forms gives your paintings a distinct psychological tension. Can you describe how you develop these visual stories within each piece?

Ambiguity in my work is intentional—it mirrors the uncertainty and fragmentation of personal and cultural memory. By redacting or obscuring details, I resist the urge to fully explain or reveal, allowing viewers to bring their owninterpretations. This invites a slower, more reflective engagement and encourages viewers to confront the gaps in their own understanding. It's a form of shared vulnerability—one that respects the complexity of experience without prescribing a fixed narrative.

Everyday objects have a central role in your work, both visually and symbolically. What draws you to them, and what do they help you express?

I choose objects that were once part of intimate, domestic settings but have since lost their economic value—items often found in secondhand markets or simply discarded. These objects carry a dual weight for me: they are tied to my personalmemories growing up in Wenzhou during China's industrial transformation, and they serve as cultural artefacts of a society reshaped by rapid consumerism. They reflect both the intimacy of lived experience and the impersonality of global commerce, becoming vessels for exploring shifting identities and human connection.

You grew up in Wenzhou during a time of big economic change. How has that influenced your view on consumer culture and memory?

Wenzhou was a site of explosive entrepreneurial energy—its streets were filled with cheaply produced goods destined for global export. As a child, I was surrounded by these objects, which were both materially insignificant and symbolically loaded. They were tools of social navigation—defining class, relationships, and aspirations. Today, I see domestic space not as a refuge, but as a stage where the pressures of tradition and modernity collide. These contradictions continue to fuel my exploration of alienation, status, and belonging.

A Happy Generation, oil on canvas, 48x52 in, 2025 © Yezi Lou

You describe nostalgia as political. What do you mean by that, and how does it show up in your art?

For me, nostalgia isn't about longing for an idealised past—it's a form of critical memory. I see it as a political emotion that mediates the tension between collective experience and personal loss. My work doesn't offer closure; it dwells in the ambiguity of unfulfilled possibilities. The objects I paint often represent moments suspended in time—echoes of futures that never came to be. This layered approach invites the viewer to consider memory as fragmented, unstable, and shaped by broader social transformations.

Your palette and composition often evoke a sense of distance or absence. How do you use colour and form to build that emotional or psychological atmosphere?

Grey tones are my most frequent strategy, offering a sense of control and comfort. The grey I often use leans toward cooler tones, evoking detachment interwoven with struggle, and at times, judgment. Its supposed neutrality is always on the verge of tipping, its openness inherently unstable. Such precariousness mirrors both my painting process and my understanding of figurative language—a constant search for balance and security between discipline and disorder, control and uncertainty, presence and concealment.

You've had several exhibitions in both the U.S. and China in the past year. How has showing work in different cultural contexts affected the way you think about your audience or the narratives within your art?

Audiences who share a similar cultural background with me often recognise specific visual cues, text elements, and cultural references in my work almost instantly—there's a shared understanding of the social and generational shifts I'm engaging with. In the U.S., or among broader audiences, responses tend to focus more on formal and emotional qualities, often accompanied by curiosity about the cultural context behind the imagery. These varied interpretations have deepened my awareness of how visual language operates across different cultural landscapes, and they've challenged me to consider how I, as an artist, can articulate complex experiences that straddle both personal and collective memory.

Yatchs, Oil on canvas, 2025 © Yezi Lou

Welldone, Oil on Canvas, 16x20 in, 2023 © Yezi Lou

And lastly, what themes or directions are you currently exploring in your MFA work, and are there any future projects or experiments you're particularly excited about?

As my exploration of objects has deepened, my focus has gradually shifted from nostalgia to a broader investigation of alienation in contemporary society. What began as a study of memory and material culture evolved into a deeper inquiry into the tension between intimacy and estrangement. In this process, Wenzhou, and my own family, became a prototype for examining the dynamics of a small yet representative social unit. During my final year in the MFA program, I developed a project that modelled the structure of a Wenzhou family, using personal narratives to explore collective experiences and question cultural norms. This line of inquiry will remain central to my practice moving forward. I'm particularly interested in reconstructing a relationship with a collectivity I once distanced myself from. Alongside this theme, I'm also drawn to questions about how information is distributed across shifting social and political landscapes. I've come to see freedom not as detachment, but as the ability to dismantle cognitive boundaries between the private and the public. The tension between individual identity and societal norms is no longer a conflict for me, but a negotiation—a balancing act where both can exist in distinct yet inseparably meaningful ways.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.