10 Questions with Chie Yoshida

Born in Gifu in 1992, Chie Yoshida graduated from the Faculty of Fine Arts, Western Painting Course 2, at Nagoya University of Arts, in 2016. After graduation, she moved to Canada, and she has exhibited in New York and Russia. She is currently based in Tokyo.

After marrying her Russian husband (quarter Russian and quarter Ukrainian), she began presenting works on the themes of war and censorship. By censoring her own work, she questions the nature of freedom of expression. Major exhibitions and awards include a solo exhibition at Shibuya Hikarie, Aichi Triennale 2019 (participated in a group), JCAT Showcase (NY), selected for the Makurazaki City International Art Award Exhibition, and selected for the Mitsubishi Corporation Art Gate Program.

Chie Yoshida - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

The invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 prompted her to censor her own work on the theme of freedom of expression.

She married a Russian husband who also has roots in Ukraine, and she visited Russia before the invasion. During that visit, she happened upon a censorship incident in which police welded the doors of a gallery to prevent an exhibition. At that time, she began to feel a sense of crisis concerning freedom of expression.

When people hear the word "censorship," they might think, "It doesn't concern me." However, even today, restrictions on expression and speech are being imposed under the guise of "compliance." Originally, compliance was meant to be a guideline to avoid hurting others. However, if this is used as a convenient excuse by those in power, it has the potential to unknowingly involve everyone in war. In other words, we are living in an era that cannot be dismissed as unrelated to censorship.

And although it has been 80 years since the end of the war, some believe it may actually be an era that could be called the "new prewar." When considering it that way, those living today should learn about the war from before the war, not just from after.

However, in Japan, there is a problem in that works from the prewar period are hardly known compared to those from during and after the war. Furthermore, even though censorship at that time is said to have occurred, those cases are not well known. It seems as if war is portrayed as something that suddenly happens, rather than something that gradually eats away at daily life, and she has felt uncomfortable about this for many years.

That is why, as an artist, she believes it is necessary to preserve in her work the memories of people and events that cannot be recorded in history books, and to leave them for future generations. She was not a participant in this war. However, seeing her loved one injured, she could not ignore this reality.

Currently, with the help of Russians in Russia, she is researching the words and events that were actually censored, and trying to preserve people's memories through her art.

She then attempted to censor her own work by superimposing a black square onto it. If an artist censors their own work, who else can censor it further? This work can be called a "correct expression" based on modern compliance. However, regarding compliance, whether to harm no one and thus uphold "the correct way of society", she questions whether this truly constitutes "beautiful expression" or "contemporary art." She is uncertain.

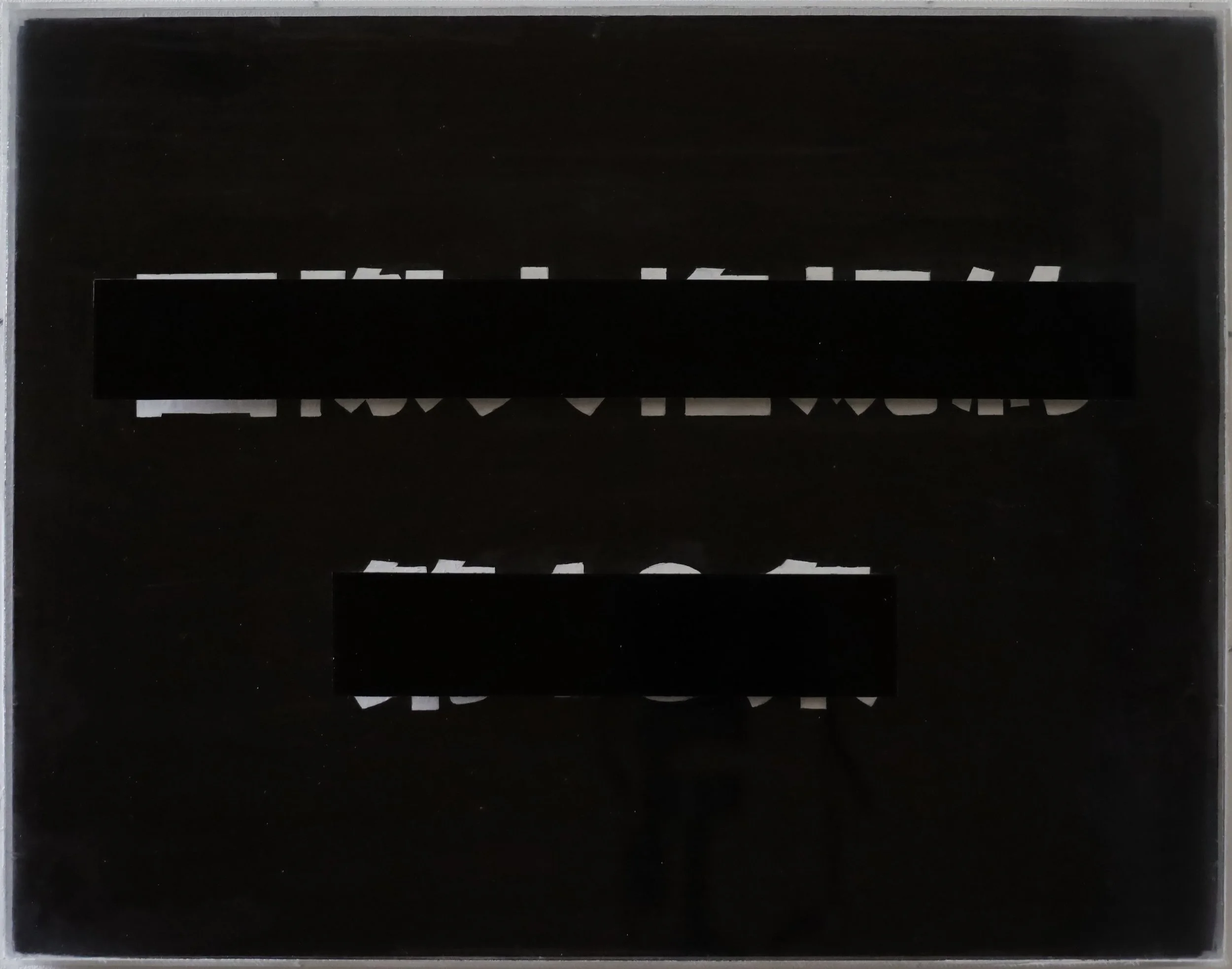

A Beautiful word, Chalk on panel, acrylic paint, acrylic box, 414 x 277 x 40 mm, 2024 © Chie Yoshida

INTERVIEW

First of all, could you start by telling us about your background and how you first became interested in art?

I became interested in art when I encountered watercolours at the age of three. As a child, I liked watercolours more than I liked art, and I attended a local art class for nine years. When I entered elementary school, I wanted to study art more and developed a strong desire to go to art school. However, the area where I lived as a child was rural, with no art museums or galleries nearby, and it was common for adults to have no knowledge of art either. Because I lived in the countryside, I had no opportunities to come into contact with artworks, so rather than becoming interested in art, I became interested in paint, and that was the beginning of my life as an artist.

What first led you to explore the themes of war and censorship in your work?

It was a censorship incident that occurred in Moscow in October 2019. In this incident, Moscow police welded together the doors of a gallery to disrupt an exhibition. The content of the exhibition was mocking the Putin regime. I had never heard of the police disrupting an exhibition in Japan, so it came as a huge shock to me, and it sparked a sense of crisis about war. I intuitively believed that "this country wants to go to war." And in February 2022, my intuition was confirmed.

A Beautiful word (detail), Chalk on panel, acrylic paint, acrylic box, 414 x 277 x 40 mm, 2024 © Chie Yoshida

A Beautiful word, Chalk on panel, acrylic paint, acrylic box, 414 x 277 x 40 mm, 2024 © Chie Yoshida

You experienced censorship firsthand during your visit to Russia. How did that moment influence your artistic direction?

Incidents of censorship in Russia are not unique to Russia. Restrictions and censorship of expression are also practised in Japan in the name of compliance. In Japan, expressions in manga and anime frequently come under fire. Compliance exists as a guideline to avoid harming others. However, I wondered if expressions that offend viewers are so bad, and if they were censored in the first place, who would complain?

In other words, I began to wonder whether society could further censor a work that the artist himself had censored. Thisled me to the idea of exhibiting the work in a censored state, allowing people to see a situation that they would not normally be able to see.

In your recent work, you censor your own paintings. What message do you hope this act conveys to viewers?

Since visiting Russia, I have come to believe that what is taken for granted is not necessarily taken for granted, and that what is normal is merely an ideal. I have come to believe that the fact that we can appreciate artworks in museums and galleries is possible because freedom of expression is protected, and that this is a very precious thing. My work may be a "correct expression" in terms of compliance. However, I would like all viewers to consider whether this "correct expression" is also a "beautiful expression."

How do you define "freedom of expression" in today's social and political climate?

That's a very difficult question. At the very least, isn't "minimum freedom of expression" the ability to express one's opinions and thoughts without being obstructed by state power?

Society today views social media flame wars as evil and tries to avoid them, but I don't think flame wars themselves are bad. It's natural for each person to express their own opinion and clash with each other. However, I think the greatest evil is preventing this clash from happening in the first place.

Free Expression, Panel with chalk background, acrylic paint, acrylic box, 414×277×40 mm, 2024 © Chie Yoshida

You've mentioned concerns about "compliance" being used as a form of control. How do you translate this idea visually in your art?

The black squares make the letters painted on the canvas difficult to see, preventing people from viewing them. However, I insisted on leaving a 4cm gap between the letters and the black square. By leaving a gap, the squares appear to obstruct the view of the letters, leading people to wonder, "Why are they hiding the letters from view?"

What's even more interesting is that anyone who shows an interest in my work always peeks at it through the gap on the side to view it. This proves that even if you censor information, you cannot censor people's curiosity.

Your work preserves memories and voices that might otherwise be lost. How do you approach this process of remembrance?

Our brains have a forgetting system that causes us to forget if we do nothing. There are a variety of efforts to ensure that the lessons of war are not forgotten. One method is to record them in history textbooks, but it is impossible to include all of people's personal anecdotes in textbooks. I believe that art can function as a receptacle for this.

I believe my works exist as devices that can evoke memories in people who look at them and think, "Oh, that reminds me, that happened in 2022. I was..."

How has your personal connection to both Russia and Ukraine affected your perspective as an artist?

They had a huge, life-changing impact. Before I actually went to Russia, there was little awareness of it as a neighbouring country of Japan, and it seemed like a closed country.

Perhaps because of this, Russian art is minor in Japan, and there are very few art school professors who are well-versed in Russian art. I grew up in the countryside and graduated from an art school in a rural area, so I was in an environment with little information about Russia.

I have the impression that Russians are very concerned about how to survive in oppressive environments. I believe this is connected to the strength of Russian artwork. I was deeply inspired by the fact that Russian artists have always desired to be able to freely exhibit their work without fear of the police.

Until I encountered Russia and Ukraine, I had not been able to find social significance in my own work. This encounter has given me a sense of purpose in my work and in my life, knowing that my work can relate to social conditions.

Our prewar, Panel with chalk background, acrylic paint, acrylic box, 414×277×40 mm, 2024 © Chie Yoshida

Our prewar, Panel with chalk background, acrylic paint, acrylic box, 414×277×40 mm, 2024 © Chie Yoshida

What projects are you currently working on, and what do you hope to explore next?

I'm currently working with the Ukrainian Embassy in Japan to plan an exhibition in Japan about the invasion of Ukraine, including my works. There aren't many artists in Japan who create works about Ukraine and Russia like I do, and Japanese people's interest in Ukraine and Russia is fading day by day.

I hope to use my work to remind people of Ukraine and to create an opportunity for them to think about the relationship between freedom of expression and war.

Looking ahead, how do you see your work and its message evolving over the next few years?

I don't think that will change in a few years. I think that evaluations will probably change after several decades.

In Japan, there are wartime and postwar works, but very few prewar works. As a result, the Japanese art history taught at Japanese art universities has the problem of missing the prewar period (1920-1940). So I think that the next wartime works exhibition needs to include prewar works as well, and that's why I'm creating my works.

Therefore, I don't think that my work will change after a few years, but rather after several decades.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.