10 Questions with Mingyong Cheng

Mingyong Cheng, originally from Beijing and now based in California, is an interdisciplinary artist working at the intersection of AI, generative art, and environmental research. She holds two BFAs from Communication University of China (CUC), an MFA in Experimental and Documentary Arts from Duke University and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Art Practice and Art History at the University of California, San Diego, with a focus on interdisciplinary environmental studies. Mingyong’s work bridges computational media arts and speculative ecology, emphasising the co-creation of generative artificial intelligence in the artistic process. Her research explores how generative AI can act as a collaborative partner, producing ecological art that transforms our understanding of and relationship with nature and the environment. By engaging AI as a co-creative force, her practice reimagines the boundaries of creativity and its potential to address contemporary ecological challenges. Her work has been exhibited internationally at leading venues, including ACM SIGGRAPH Asia, SIGGRAPH and Creativity & Cognition, the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), the International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA), the IEEE / CVF Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference (CVPR), and other global art and technology forums. Her work won the Gold Muse Design Award 2025 in the Artificial Intelligence category and was also recognised as the winner of the 2025 Digital Arts Student Competition Speculative Futures.

Mingyong Cheng - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

“My artistic research investigates speculative ecology in the age of generative AI, where artificial intelligence becomes not just a technical process but a speculative partner in reimagining human-environment relations. By engaging AI as a cultural and ecological interlocutor, my practice explores how synthetic systems can evoke alternative ways of sensing, remembering, and coexisting with the more-than-human world. Working across generative animation, performance, real-time systems, and immersive installation, I develop hybrid environments where nature, data, and memory converge through machine vision and embodied experience.

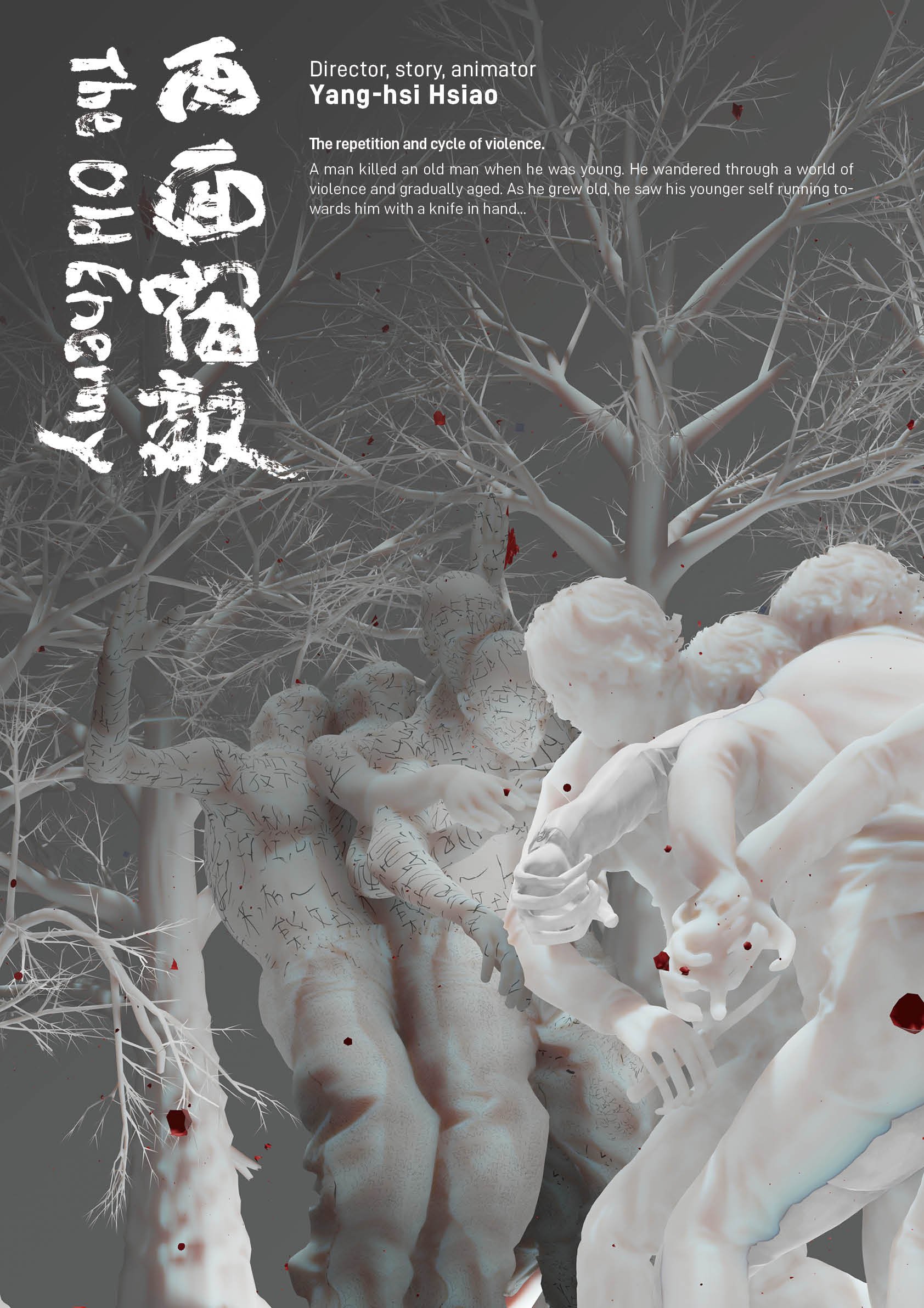

Fusion: Landscape and Beyond (V1) is a foundational project that reflects my inquiry into AI memory and cultural aesthetics. Trained on over 2,000 raw image samples of Chinese shan-shui (mountain-water) painting, the AI was fine-tuned to generate synthetic images that fuse traditional landscape motifs with contemporary spatial logics. This version includes a video animation titled The Faded Landscape and a set of AI-generated stills using image-to-image transformation techniques. Inspired by the enduring pigment and vision of Thousands Li of Rivers and Mountains, the animation charts a transition from natural to urban topographies, evoking a tension between cultural permanence and environmental degradation. This fusion is not illustrative but speculative, where machine-generated terrain becomes a site for questioning the temporal layers of landscape, memory, and artificial perception.

Learning to Move, Learning to Play, Learning to Animate (2024) extends this inquiry into the realm of live performance. Through the integration of plant biofeedback, found-object robotics, and real-time AI-generated visuals, the piece constructs a participatory system where human and nonhuman intelligences learn through interaction. Rather than following a choreographed structure, the performance embraces emergence, foregrounding mutual responsiveness between bodies, signals, and systems. It invites the audience to reconsider intelligence as something relational and embodied, not isolated in any one species or entity. Animation here becomes a porous boundary between agents—moving, sensing, and becoming together.

Visual Interpretation of Lei Liang's "Six Seasons" continues this speculative trajectory by transforming Arctic environmental sound into generative visual animation. In dialogue with Lei Liang's orchestral composition, this project allows AI to listen and respond visually, forming a space of contemplation around ecological transformation. Rather than visualising sound directly, the system draws on ecological data and environmental textures to generate a continuously shifting image field, attuned to the temporality of melting ice, migratory silence, and vanishing habitats. The result is a poetic interface where the fading ecologies of the Arctic are neither documented nor dramatised, but reinterpreted as ambient memory through the speculative lens of machine perception.

Across these projects, my work proposes speculative ecology not as a theme, but as a method—one that invites generative AI to act as a companion in exploring cultural residues, environmental futures, and the unstable borders between the real and the synthesised. These pieces do not offer conclusions but open a space for multi-scalar perception and ecological imagination, where the digital is no longer outside of nature, but deeply entangled within it.”

— Mingyong Cheng

Visual Interpretation of Six Seaons, Audiovisual Video Art, 6 videos in total, 60min, 2024 © Mingyong Cheng

INTERVIEW

Your background bridges art, technology, and environmental research. What led you to explore this intersection so deeply in your practice?

My interest in this intersection began with a longstanding fascination with nature and digital media. I was originallytrained in film and digital journalism, but over time, I became more interested in forms of storytelling that didn't rely on fixed narrative structures. During my MFA at Duke, I started working with generative AI and discovered its potential to engage with ecological questions in a non-linear, responsive way. I continued to deepen this exploration during my PhD, where I began developing interactive and speculative systems that blend real-time media with ecological thinking. I see AI not just as a tool, but as a creative collaborator that helps me rethink how we relate to the environment, through shared agency, adaptive systems, and the poetics of data.

How do you see the role of generative AI evolving within the field of ecological art? Can machines truly become creative collaborators?

Generative AI is changing how artists approach ecological questions. I don't see it as a passive tool but as an active collaborator that contributes to the creative process. AI systems can recombine ecological and cultural data in ways thatbring forward unfamiliar relationships and unexpected forms. This helps challenge established assumptions about nature and opens up new ways of working. Collaboration with AI is not about giving up agency—it's about engaging in a process where both human and machine shape the outcome together. The model generates material, I respond to it, and the direction of the work shifts in response to both. This kind of dialogic process or feedback loop is central to how I think about creativity today.

The way I approach this collaboration is shaped by a perspective I call speculative ecology. It's a way of thinking through ecological issues that emphasises uncertainty, entanglement, and possibility, rather than fixed systems or stable representations. Rather than depicting nature as something external or harmonious, speculative ecology sees it as dynamic and constantly reshaped through interactions between human and non-human forces—technological, biological, and otherwise. From this view, ecology is not just a subject but a shifting relation that includes data, memory, sensation, and narrative.

In this context, AI becomes part of that ecological relation. It introduces its own form of memory—drawn from training data, shaped by algorithms, and expressed through generated forms. These outputs often exceed my expectations, opening new questions I wouldn't have asked on my own. Working with AI in this way is not about efficiency or automation, but about expanding the range of ecological imagination. It allows for emergent connections and alternative visions of how we relate to the world, ones that are shaped not just by what we already know, but by what machines are capable of remembering, recombining, and revealing.

From Landscape to Landscape, AI Painting Scrolls (in total 8 in a series), 22.05 x 47.25 each, 2024 © Mingyong Cheng

In your project Fusion: Landscape and Beyond, you trained an AI on shan-shui paintings. What did you discover about tradition and memory through this process?

In Fusion: Landscape and Beyond, I fine-tuned the Stable Diffusion v4.1 model on a self-curated dataset of shan-shui paintings, in collaboration with Xuexi Dang. Rather than building a model from the ground up, we introduced it to a visual tradition that has continuously evolved over centuries. Shan-shui is not only an artistic form but also a mode of perception, a way of relating to nature, and a cultural presence that extends into everyday life through poetry, philosophy, and spatial design. Its aesthetics have never remained static. They have shifted in response to changing social, political, and environmental conditions while retaining their conceptual foundations.

Working with AI in this context helped me see the model as a form of memory. Fine-tuning allowed the AI to internalise the visual grammar of shan-shui and reconfigure it in ways that did not simply reproduce but reactivated and recombined inherited forms. I began to understand this process as a kind of "AI memory". The model recalls and synthesises fragments of tradition, making them visible in forms that are both unfamiliar and strangely resonant.

This experience challenged the notion that tradition must be preserved unchanged. Instead, it revealed that cultural memory can be carried forward through transformation. AI has become a participant in the longer history of shan-shui's evolution, engaging in the same process of adaptation that has defined the genre for centuries. Rather than being outside of tradition, the AI becomes a new voice within it, suggesting that memory and cultural continuity can unfold through processes of reinterpretation, recombination, and creative negotiation.

Many of your works, such as Learning to Move, Learning to Play, and Learning to Animate, involve live interaction. What draws you to real-time systems and performance?

Real-time systems allow me to create situations in which the audience isn't just observing but participating. I'm drawn to the unpredictability of these systems—the way something changes depending on how someone moves or how data flows at that moment. This kind of interaction mirrors the behaviour of ecological systems—nonlinear, adaptive, and responsive. I also see real-time environments as places where human and non-human elements collaborate. Whether I'm working with AI, sensors, or biofeedback systems, the performance becomes a shared process. It's not about control; it's about exchange. That's where I feel speculative ecology comes into play, especially in Learning to Play and Learning to Animate—not as a theme, but as a working method that reveals interdependence and ongoing transformation.

You describe your installations as "hybrid environments" where nature, data, and memory converge. How do you approach building these immersive ecosystems?

For me, building these environments starts with a question—something I want to explore about how we relate to ecological systems, or how memory and perception shift through technology. I begin by researching the topic deeply, not just conceptually but also visually and emotionally. I collect materials that feel relevant—environmental data, archival images, fragments of text, sensory recordings—and then look for ways they can speak to each other.

I use tools like generative AI and TouchDesigner because they let me create systems that respond in real time to movement, sound, or other inputs. But the goal isn't to show off the technology. It's to create a space where the digital elements feel inseparable from the organic ones, where everything contributes to a shared atmosphere. I think a lot about how to build interactions that feel intuitive, where people can enter the work physically or emotionally without needing instructions.

Memory plays a big role in this process. I'm interested in how cultural and personal memories are stored, distorted, or reactivated—both by us and by machines. So I try to design the space in a way that makes room for reflection, not just stimulation. It's less about spectacle and more about creating an experience that lingers, that stays with people after they leave the space.

What are the challenges or limitations you've encountered when working with AI as a speculative tool for environmental storytelling?

One of the practical challenges is that the quality of the AI-generated content isn't always reliable. Sometimes the images or sequences need a lot of additional processing to reach the visual or emotional effect I'm aiming for. On the other end, there are moments when the AI generates outputs that are so overly specific or literal that they leave little room for interpretation. Other times, the results are too abstract or disconnected from the ecological themes I'm exploring, which makes it hard for the work to hold the tension or nuance I want.

So a lot of the process becomes about navigating that balance—finding what feels resonant, refining what doesn't, and learning how to work with the system almost like I would with another collaborator. It's unpredictable. It takes time to get to know what the model is capable of, how it responds, and how to shape its contributions without forcing them into something they're not. That back-and-forth is part of what makes it generative, but also what makes it slow and experimental.

There are also environmental and ethical concerns that I think about regularly. AI systems, especially large models, have real ecological costs in terms of energy and resource use, and they often rely on training data scraped from complex and sometimes problematic sources. When working with ecological themes, it feels especially important to be aware of what kinds of visual narratives are being repeated, and to avoid aestheticising environmental collapse in ways that feel disconnected from lived reality.

At the same time, speculative storytelling through AI offers a way to imagine relationships and futures that are not easily represented through traditional media. However, because these systems operate through pattern recognition, they can reinforce familiar tropes unless we are intentional about how we prompt, curate, and frame their outputs. That's where the work becomes less about control and more about careful engagement, recognising that the machine brings its own logic, and learning how to listen to it critically while staying accountable to the ecological questions that matter to me.

Learning to Move, Learning to Play, Learning to Animate, Multimedia Performance, 20min, 2024 © Mingyong Cheng

Learning to Move, Learning to Play, Learning to Animate, Multimedia Performance, 20min, 2024 © Mingyong Cheng

Your use of machine vision and environmental sound, like in Six Seasons, feels poetic. How do you balance scientific data with artistic intuition?

Six Seasons was created through a close collaboration with composer Lei Liang and oceanographer Joshua Jones. The work draws on underwater sound recordings from the Arctic Ocean, environmental datasets, and seasonal satellite imagery. These materials shaped both the structure and the atmosphere of the piece, but my goal was not to translate them directly. I wanted to create an experience where these layers could be felt and sensed through time, through sound, and through shifting visual textures.

I started by fine-tuning six LoRA models of Stable Diffusion on visual datasets that reflect different Arctic seasonal transitions. These were combined with a DreamBooth model trained on traditional Chinese shan-shui paintings. The AI-generated images were pre-rendered, but they did not function as static elements. Within TouchDesigner, I reprocessed these visuals using the original ecological data and the live structure of Lei Liang's multichannel composition. The system allowed the pre-generated imagery to react in real time to changes in the soundscape, creating a visual field that was responsive and fluid.

In this project, AI functioned less as a content generator and more as a memory system that could be activated and reshaped in response to environmental presence. Scientific data gave me the foundation, but it was intuition that guided how the images moved, how they lingered, and how they shifted over time. I listened closely to the recordings, not just for meaning but for rhythm, density, and emotion. That guided how I composed the visual transitions and how I allowed moments of stillness and transformation to emerge.

For me, balancing data and intuition means staying close to the material but not being limited by it. I am not trying to explain the Arctic, but to offer a way to dwell with it. The work is shaped through care, through response, and through an ongoing conversation between ecological systems, human interpretation, and machine memory.

Speculative ecology is central to your work. How would you define it in your own terms, and what role can it play in reshaping our ecological imagination?

I think of speculative ecology as a way of rethinking our relationship with the environment by moving beyond fixed systems and anthropocentric views. It brings together ecological thought, speculative philosophy, and artistic practice to explore how humans, non-humans, and technologies are entangled across time and scale. Rather than aiming to represent nature as it is, it asks what could be—what kinds of ecological relationships, narratives, and futures we can imagine.

For me, speculative ecology is also about recognising that knowledge and perception are always partial. It opens space for multiple perspectives, including machine intelligences, and invites us to consider forms of agency and interdependence that often go unnoticed. In my practice, it becomes a method to work through uncertainty by collaborating with generative AI, for example, I'm not illustrating nature but co-thinking with systems that carry different kinds of memory. This helps unsettle familiar representations and allows for more open, layered, and reflective ways of engaging with ecological questions.

You've presented work in art and tech contexts, from ISEA to CVPR. How do audiences differ, and does that shape how you present your projects?

The audiences at places like ISEA and CVPR can be very different, which definitely shapes how I talk about my work. In art contexts, people are usually more interested in the conceptual grounding, the poetic or speculative questions, and how the work engages with broader cultural or ecological themes. There's often space for open-ended interpretation and critical dialogue.

In tech-focused spaces like CVPR, the emphasis tends to be more on process—how the system works, what kind of data I used, and what's new or experimental in the technical setup. So when I present there, I focus more on how I trained or fine-tuned the models, what tools or workflows were involved, and how the system performs or responds.

I don't change the core of the work, but I shift the language and framing depending on who's in the room. I've come to see this as a strength—it pushes me to think through my projects from different angles and to make the ideas accessible in more than one way. That flexibility has helped me understand my own practice better and connect with a wider range of people across disciplines.

What new tools, collaborations, or ecological questions are you excited to explore in your next projects?

Lately, I've been exploring a few different directions that expand how I think about ecology, perception, and machine systems. I recently completed a collaborative audio-visual piece with composer Nathan Hearing that draws on the scientific phenomenon of sonoluminescence—this idea of sound creating bursts of light at a micro level felt like a poetic way to think about energy, transformation, and unseen environmental forces.

At the same time, I'm deep into my PhD research, which looks at the relationship between fractals, ecological thinking, and bio-data. I'm especially interested in how biodata can be used to shape generative systems that reflect more-than-human rhythms and patterns. It's a way of asking how bodies, environments, and algorithms can learn from each other.

I'm also excited to be serving as both creative technologist and artist in the upcoming exhibition Dancing the Algorithm, curated by Katherine Helen Fisher at Jacob's Pillow's new Doris Duke Theatre this summer. It's a performance-centred project that asks how choreography and computation can inform one another in the digital age. In a different context, I'll also be part of a collaborative audiovisual show at Peabody with Safety Third Productions for guitarist Zane Forshee, where I'll be working with real-time reactive visuals shaped by sound and movement.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.