10 Questions with R. Scott MacLeay

Al-Tiba9 Art Magazine ISSUE19 | Featured Artist

R. Scott MacLeay holds an MSc from the London School of Economics and left his doctoral studies to pursue a career in photography in Vancouver, moving to Paris in 1979 to dedicate himself to his exhibition work. He has exhibited widely in galleries/museums in Europe, North and South America and Asia, and his images are present in numerous private and museum collections. His passion for video art began in the early 80s, and in 1985, he was named Director of the prestigious Centre for Media Art and Photography of the American Centre in Paris. He left the world of analogue photography in 1988 to compose contemporary music for video art, special format cinema, contemporary dance and his musical research group Private Circus, an activity that sparked his interest in digital imagery and online technologies. Since moving to Brazil in 2010, he divides his time between new media creations, musical composition for installations and exhibitions, writing and the exploration of online interactivity. Over the past four years, his video works have won awards in film festivals in London, Paris, Cannes, Berlin, Milan, Florence, Venice, Amsterdam, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Hong Kong and Shanghai.

R. Scott MacLeay - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

R. Scott MacLeay views all lens-based art as documentary, regardless of the subject. Some artists document the “real” world, while others like MacLeay, create the worlds they explore. Because he is what he thinks and feels, not what he sees, his work represents an incessant exploration of innovative linguistic structures capable of translating thoughts and feelings into concrete forms. His new media art deals with existential themes, often employing the first person in performance-based work. He explores situations rather than moments and as such, his work is focused on notions of evolution, transformation and repetition with chance interference often playing a decisive conceptual role. MacLeay believes we are who we are and where we are due to our education, our decisions and the continual stream of uncontrolled outside interference that affects our perspectives and choices, altering our destiny. Life is a process, and in art, as in life, process is content. He considers outcomes less thought-provoking than the dynamics that determined them, just as doubt and ambiguity are more relevant to understanding than the prison of certainty. Risk-taking is fundamental.

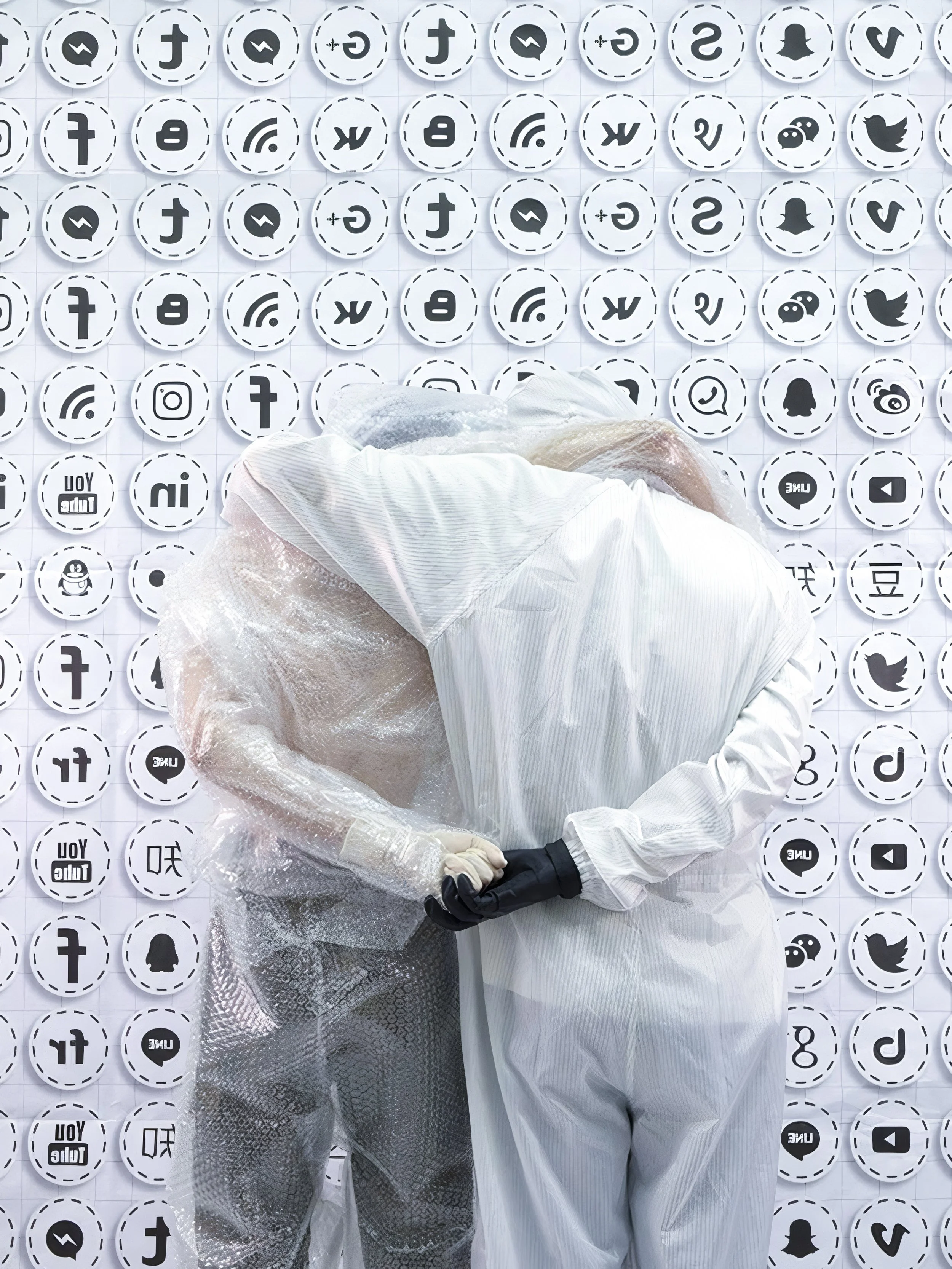

Back and Forth, Digital - Gyclée Print from the video piece “Past Present … Tense”, 27x27.58 cm, 2019 © R. Scott MacLeay

Dealing with the ambiguity of a growing relationship between two people in which neither person truly understands the motivations and actions of the other, R. Scott MacLeay’s interactive, performance-based transmedia project “Encounters in the Right and Left Hemispheres” explores the role of chance in the relationship development between two persons of different ages and backgrounds. An interactive book tracing the chronology of their performance encounters (Creative Process, 2020) and an interactive Web platform (2021) exploring their encounters from either the male or female perspective, chronicle their journey from different perspectives.

AL-TIBA9 ART MAGAZINE ISSUE19

Get your limited edition copy now

INTERVIEW

Throughout your career, you have worked with several different media and projects, spanning photography, video art, music, writing, and digital media. How would you describe who you are as an artist today?

I would describe myself as a new media artist working with digital tools in the fields of photography, graphic art, video and music. The communicability of these fields among one another has increased dramatically over the past 2 decades, and I see them as sibling vehicles of expression.

You left your doctoral studies to pursue photography. What was the turning point that convinced you to take that leap into a full-time artistic path?

Boredom. I knew from the outset of my university studies in the field of economic theory that I would probably never work professionally in the area. The fact is that I never really wanted to go to university. At 18 years of age, I would have been perfectly happy to continue playing keyboards in a blues/R&B band as I had been doing since I was 16. I decided to attend university because I felt I owed it to my parents, and to be honest, I was genuinely interested in understanding the micro- and macroeconomic relationships responsible for shaping so much of contemporary life. After finishing my Master’s degree at the London School of Economics, I decided to return to Canada for my doctorate, and five months into the program, I was bored. I decided to take an evening course in black and white photo laboratory techniques to break the monotony. The course was held once a week in the evening over an 8-week period. The day after the last class, I walked into the office of my academic adviser and quit my doctorate, returning all my scholarship money. I was flat broke, but I felt reborn. I had never taken photos before entering the class, but somehow, I knew my destiny lay in this area. I had no doubts whatsoever. I was back where I belonged, exploring ways of expressing myself that were relevant to me. However, it is important to note that my years of studying economic theory have served me well throughout my career, offering valuable insight into ways of synthesising themes and reducing the complexity of reality via the careful selection of key interactive parameters to exploit in pursuit of specific narratives. I am a theoretical artist in the service of a practical vision.

Your career has crossed analogue and digital eras, with a major shift in 1988 toward music, video, and later, online interactivity. How has moving between these media shaped the way you think about visual art?

For the past 37 years, I have been totally immersed in the digital universe, beginning with my move from analogue photography to electronic music composition, sound design and recording in 1988. At that time, analogue photography was unable to accommodate the type of multilayered/multigeneration images I was interested in exploring. Music had entered the digital domain via sound synthesis, sampling and digital recording and was advancing rapidly. It was perfectlysuited to handling my creative preoccupations at the time. Since I had begun composing music for contemporary dance shortly after moving to Paris in 1979, the decision to devote myself exclusively to musical creation was a relatively natural one. I began composing for the video artwork of French artists, and this, along with a growing interest in performance art, led me to begin exploring the digital media arts in general. Today, I divide my time between performance-based video works and installations and still digital works involving a combination of photography, drawing and production techniques in the digital domain.

I relate this history because it illustrates how each move further into the digital domain was in response to specific demands that I felt necessary to more accurately express myself. I was never preoccupied with producing traditional photographic works dedicated to 2-dimensional representations imitating the 3-dimensional world I saw around me. I am what I think and feel, not what I see and for me, the digital world and its tools seemed far more capable of representing these states of mind than the analogue lens-based world. The possibilities seem limitless with the constant expansion of colour palettes and textural renderings, easy access to an ever-growing family of video production tools and effects, not to mention the possibility of introducing public participation into our narratives online and in real-time, all of this with a common digital language and technical methodology. It seems to me that for those artists like myself interested in non-linear interactive narratives, the digital universe offers a panorama of possibilities that are both unique and ever-evolving.

The digital domain is by definition a pluri-disciplinary universe with common threads running through all the mediums it encompasses, generating a family of close relationships. I am no longer a photographer and/or a video artist and/or a composer. I am simply a new media artist. I realise that this label often poses a problem for the public, but the problem is theirs, not mine.

In your statement, you’ve said that in lens-based art, you create the worlds you explore. Could you walk us through how one of these imagined worlds begins to take form, from concept to finished work?

From the outset of my journey as an artist, I have always created the worlds I explore. In some fundamental way, it could be compared to the way that social scientists build what appear to be highly simplified, apparently unrealistic models of society capable of generating a better understanding of how our very complex real world works. In response to your question, there is one particular example of my creative process that led to three separate works over a 12-year period, which I think may be of interest. The following exposé is a bit lengthy, but I think it accurately illustrates the inevitable interconnectivity of themes that preoccupy us.

The first serious analogue photographic work I completed was the series “Attitudes”, which was exhibited at the Space Gallery in New York in 1980 (extract). The series dealt with the notion of beauty as an alienating force, isolating people from the reality of day-to-day life and from the priorities that actually determine our quality of life. I had worked as a fashion photographer in Vancouver from 1977 until 1979, and although I found the work creatively challenging, I did not appreciate the commercial fashion environment, particularly the way in which female models were regarded and treated by modelling and advertising agencies. In 1978, I began the series Attitudes as a way of expressing my frustration with the fashion world and what I saw as the hypocrisy of many of its messages.

I formulated two priorities for the series: it must address the superficiality I perceived and the alienation it provoked. I decided that the notion of superficiality could be best expressed through the use of detail-free, flat forms with no perceived depth, texture or volume – no substance. This required that I experiment over several months with the lighting of various materials (fabric, paper, wood, metal, etc.) in combination with colour film exposure/development configurations that were capable of rendering the lack of depth I was seeking. This was the analogue world, and our control of colour was very limited - nothing faintly resembling the vast panorama of possibilities that exists today.

The notion of alienation was to be expressed by the use of single expressionless figures whose relationship to their environment was physically detached, isolated, even from objects around them. The persons were to have no contact with their environment.

My objective was to create images that were beautiful in a traditional sense, employing attractive models in graphic studio environments characterised by agreeable colour palettes in pastel tones that conveyed a peaceful sense of well-being. The result was a series of aesthetically pleasing 2-dimensional flat-field images inhabited by silent persons frozen in time, lacking the perspective, detail, depth and volume normally sought after in traditional photography. I had the combination of superficiality and beauty I was seeking. The series enjoyed considerable success and was exhibited widely in Europe, N. America and Japan.

While I was creating the series, I often thought it would be interesting to explore what was going on in the minds of the persons inhabiting the imaginary world I had created, and three years later I began work on the series Primates 1s, 2s and 3s dedicated to precisely this theme. It dealt with our image of self and with our relationships with the one or two people close to us – a study of the mindset of the contemporary nuclear family. Instead of the pastel-coloured, detail- and volume-free figures and environments of Attitudes, this new dichromatic work employed very dark, earthy tones, emphasising volume and weight with people clutching one another in almost desperate, albeit detached manners. The series was shown in New York at the Marcuse Pfeifer Gallery, and extracts were part of the international exhibition Splendeurs et Misères du Corps at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris.

I had decided from the outset that Primates 1s, 2s and 3s would be Part 1 of a trilogy with Part 2 dealing with the relationships encountered in small groups of 5-10 persons and Part 3 with relationships characterising large crowds. I worked with a small group of models for several months and was completely dissatisfied with the results I was obtaining. The second phase of the trilogy appeared to be doomed. During this period, I was devoting more and more time to composing music for contemporary choreographers and video artists in Paris and in my spare time, I had begun to workon some very personal music for a group of my own I hoped to form. Some of this work began to take on the form of a non-linear narrative about a group of nocturnal marginals, and it occurred to me that Part 2 of my Primates project was perhaps better served by a musical treatment than by photography. The result two years later was the contemporary cabaret opera Les Petites Foules (Small Crowds) released in 1990 - a collection of nocturnal arias and urban love songs tracing the aimless wanderings of a small group of marginals lost in a series of nightly processions, alienated from the daylight world of “normal” interactivity.

My concrete frustrations with two years of fashion photography in Vancouver from 1977-1979 had given conceptual birth to two series of analogue photographs during the period 1978-1985 and the composition and recording of a contemporary opera from 1988 -1990. I had learned two important lessons: there are simply no definitive destinations, and failure teaches valuable lessons if we pay attention.

Existential themes, ambiguity, and chance are central to your work. How do you translate these abstract ideas into visual and experiential forms that resonate with an audience?

I see uncertainty permeating literally all aspects of everyday life. The fact that we often prefer to ignore its implications in no way nullifies its concrete impact on our lives and their evolution. Uncertainty nourishes ambiguity. Only fools embrace certainty as a generic guiding rule. Informed understanding provokes doubt, and the only thing I am sure of is that I have doubts about almost everything.

How to translate such a position? It took me years to feel comfortable with this question, but it was resolved in large part by my study of the works and philosophy of John Cage and his use of chance techniques. This transformation in my thinking took place during the last years of my analogue photographic period, when I began progressively prioritising musical creation and work in the performing arts. I associated the theoretical notion of chance with the more general notion of interference, that often uncontrollable, unpredictable force which interrupts and perturbs our plans.

My translation of ambiguity and uncertainty in my work was, and continues to be achieved by introducing various forms of interference into the process of creation. This interference can be introduced at any given point in the creative process, from its conceptual phase through the realisation phase to the presentation phase. Sometimes the interference is carefully planned or rule-based (although its outcome remains unknown): other times it is completely uncontrolled. Very simpleexamples of rule-based interference at the conceptual phase might consist of setting a time limit for the realisation of an abstract piece – say three minutes or setting in motion a series of specific movements between models in a defined space and taking a picture every “X” seconds as I did in my series “Le Metro”, thereby yielding control of the framing and composition of the images to chance. I have often found that such practices, which do not provide the brain with an opportunity to reflect and analyse, often reveal innovative results that open new vistas of exploration we might never have explored. They may also offer results that are somehow related to our organic selves.

An example of interference at the presentation phase of an exhibition can be found in my exhibition Fragments, Cycles, Sons for the Mois de la Photo in Paris in 1982. I asked a theatrical lighting designer to create a non-repetitive cycle of lighting in the gallery labyrinth I had created, which only permitted one wall panel at a time to be lit and visible to the public, thereby perturbing their ability to see the exhibition as a whole or to control what they would see next. It seems to me that we are systematically focused on creating comfortable experiences. I was interested in making the visitors uncomfortable. It seemed to me to be much more in phase with the content I was proposing and the processes employed to create it.

Looked at from this perspective, in some very fundamental way, the process becomes the content. The realism of the work is to be found in the way it is created as much, if not more, than in the final result.

Once again, I have found that working in the digital domain greatly expands the possibility of employing interference of all types at all stages of my work.

Your project Encounters in the Right and Left Hemispheres spans performance, video, an interactive book, and a web platform. How did working across so many formats change or expand the story you were telling?

Put very simply, it permitted the presentation of different perspectives on the same performance-based narrative. In the period 2010-2012, I became increasingly interested in the notion of transmedia presentations, that is, addressing a common experience or narrative from different points of view on different media platforms, resulting in the creation of a more complete universe.

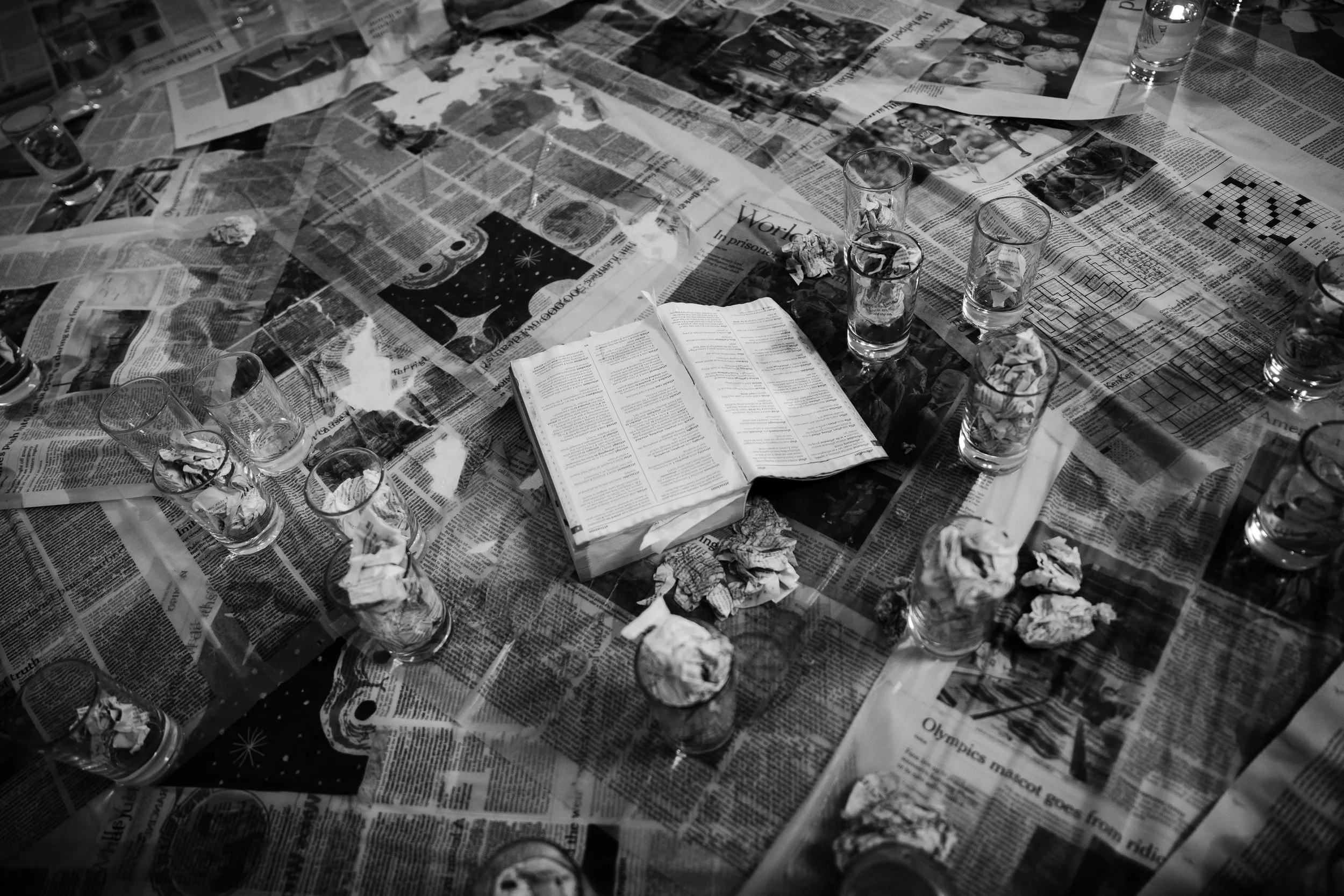

Encounters in the Right and Left Hemispheres (2017-2021) was the first project I approached in a transmedia framework. The theme was relationship development by chance between two people, and the instigating premise was a game of action/reaction I created to imitate real-life situations in which the communication between two people is often based on misunderstandings and uncontrolled interference with their interactions. The idea was that each physical encounter would involve an action drawn by chance by one person and a reaction drawn by chance by the other person from separate bags, each containing ten options. Each participant was obliged to enact the action or reaction they had drawn on the other person. Because there was no control over whether or not the reaction would constitute a coherent rational response to the action, the process allowed for simulations of misunderstandings and existence of mixed signals. Once the initial action/reaction was completed, each person was free to continue or to stop their interaction based on what had already transpired. The encounters were filmed, and the basic rule was that no editing of the results could occur. Over 60 such encounters were filmed over a six-month period.

It was also the first time that I included myself as a subject in my work. I became a performance artist, and during a six-month period, I chronicled the development of the evolving relationship between Tássya Karasiak and me via a series of staged action/reaction encounters, which slowly evolved to include a variety of other elements.

From the outset, my objective was to create an interactive book of photos of the key moments of our encounters linked via QR codes to the videos from which they were extracted. This would permit the viewer to have a multimedia experience involving the book and their cellphones whenever they chose to do so. The book’s objective was to trace the evolution of our relationship chronologically (extract of book here). The second part of the transmedia experience was the creation of an interactive Web-based platform in which the viewer could choose between the masculine or feminine perspective on the relationship’s development. On this platform, the viewer would decide what aspect of the relationship they wanted to explore and to what depth. The final phase would be a physical installation involving photographs, video projections, video monitors and texts permitting a simultaneity of sound and images unavailable in a book format and/or on an interactive online platform.

What began as a game of action/reaction encounters that I expected to last two weeks progressively evolved into a far more complex situation involving interviews, intimate testimonies, and new chance-based events. Why? Because of the unexpected impact on both myself and Tássya of the initial action/reaction encounters. We simply had to continue to explore. The combination of a performance art foundation framed by rules of encounter that provoked unexpected responses was too rich to simply stop. The experiences had to be allowed to grow until there was a mutual understanding that the process had run its course. This occurred quite naturally six months after we had begun. The depth of experience was made possible by the initial transmedia framing of the project involving the exploration of different perspectives of the same set of experiences. The process itself imposed depth of purpose. All my subsequent video pieces draw from the experience gained during the creation and production of Encounters in the Right and Left Hemispheres.

In works like Back and Forth, you explore relationships through layered perspectives. How do you use interactivity to shape or even disrupt the way a viewer experiences those narratives?

Up until now, I have not used interactivity as a parameter linked to a single isolated image. Instead, I tend to employ it in the context of non-linear narratives consisting of a series of works or of an installation. Back and Forth is a still image taken from the video “Past Present…Tense”, which is part of the project Encounters in the Right and Left Hemispheres.Interactivity is a way of enhancing our understanding of a particular theme via the introduction of an element of control on the part of the viewer, which expands their perception of the issue in question, and at the same time, it can also constitute a way of interfering with a more conventional linear appreciation of the theme. This is particularly the case when a still image with an apparently straightforward message is linked to a video like Past Present …Tense, whose slow motion and audio track convey a message potentially very different from that of the still image. In this way, interactivity acts as an agent of interference and its presence becomes part of the content rather than simply a vehicle to access other content. While it normally acts as a means of accessing recorded stills, videos or audio content, it can also constitute a real time component of content in an installation, as it will be in my upcoming project “The Choir of Discontent” - a project exploring the impact of the messaging noise caused by the simultaneous transmission of billions of messages on internet platforms every day around the world. Visitors to the installation will be invited in real time to add their frustrations, hopes and fears to the chorus of recorded participants from around the world, thereby altering the content of the work.

You’ve exhibited in galleries and museums worldwide, and your video works have been recognised in festivals from London to Shanghai. Have you noticed differences in how audiences from different cultural contexts engage with your art?

Surprisingly, I have not noticed this so much in my performance-based video works. I say this, but in fact, as I am rarely present when such works are presented in festivals worldwide, I am not able to discern if the reasons for their success are the same or similar from culture to culture. Perhaps the universality of the themes I explore is responsible for a certain homogeneity of reaction to certain works. On the other hand, my Web-based interactive project Encounters in the Right and Left Hemispheres has definitely generated more interest in European and South American countries than in North American countries. America or Asia. Perhaps the indiscreet nature of much of this project is less troublesome to mindsets less prudish in nature. I can’t really say.

Concerning my still images or musical works, the reactions tend to vary considerably in different cultures. For example, my early analogue photographic works were very popular from the outset in Japan. The flat, detail-free fields of colour and skin tones that I employed in early series, such as Attitudes, were inspired by my passion for Ukiyo-e wood block prints, particularly the works of Utamaro, and I always wondered if the Japanese interest in my early work had some connection with this fact. In general, my early colour works also generated more interest in the USA, particularly in New York, than in Europe - the European art world being more interested in my more abstract monochromatic work from this period. On the other hand, my more recent new media work, including the abstract works, seems to generate more interest in Europe and Asia than in the USA. But once again, are such preferences rooted in deeply embedded cultural references or simply a reflection of passing art market trends. Frankly, I have no idea.

In the musical domain, I can definitely affirm that my music is more appreciated in Europe than anywhere else, particularly my cabaret opera Small Crowds and the works composed for contemporary dance. I think this may be due to the fact that, in my experience, what might be labelled as marginal types of music in N. America are, in fact, far less marginalised in Europe – the European music scene being, in my view, much richer in variety and depth than the more commercially-oriented N. America scene.

You’ve said that in both life and art, process is content, and that risk-taking is fundamental. Can you share a moment when taking a creative risk completely changed the direction of your work?

There have been several, but a recent example stands out among them. The project Encounters in the Right and Left Hemispheres was originally conceived to be a modular work involving structured chance-based encounters between various pairs of people beginning with a duo that included my wife Eliana and Tássya Karasiak. We had held several preliminary meetings about the project, and it was set to start in late 2016. In the autumn of that year, my wife was diagnosed with a very aggressive form of cancer, and so all my projects were placed on hold. She passed away early in 2017, and it was a very difficult time for me. In June 2017, I knew that my well-being required that I get back to work, and the only project that was in the works was “Encounters”. Almost without thinking, I contacted Tássya and asked her if she would mind if I took Eliana’s place in the project. I was desperate to get the project underway without any further delays. I had never been the concrete subject of any of my work and had absolutely no experience as a performance artist. I knew I was taking a big risk, but it just seemed like the natural thing to do. I didn’t think about it. I just made the decision. Tássya agreed, and so we began with a rather long session of chance-based encounters based on the rules of engagement I had set out for the project. Our first session was as intense as it was surprising in its impact on both of us, and we agreed that we should organise another session. What had been originally designed as a series of single-session encounters with a variety of different participants evolved into a six-month series of encounters between Tássya and me. With my involvement as a subject, the project took on a much more subjective perspective. It was a voyage of personal discovery as much as it was of artistic exploration on a conceptual level.

I had become a performance artist by chance, and it completely changed the direction of my video work. Since then, all of my video pieces have involved my presence as a performance artist. In early 2017, I would have never been able to imagine such a situation.

Lastly, what kinds of projects, ideas, or creative experiments are you most interested in exploring in the coming years?

My desire to create in multiple fields will undoubtedly continue. My still imagery, video works and musical projects feed off one another in an almost organic fashion, and I can’t imagine this ongoing exchange not continuing. I plan to have interactivity play an increasingly innovative role in both online and installations. Also, although I cannot predict precisely how, I envisage AI will be involved in one form or another in some future projects. I have already experimented with its ability to supply me with models for my recent project “Challenged”, dealing with the trials of growing old.

Lastly, I would also like to design and create more works involving collaborations with artists in different parts of the world. I miss the collaborations with choreographers and video artists that were such an important part of my work in Paris. I am currently working on a project entitled “The Choir of Discontent”. It is an international project involving collaboration with video artists in various countries around the world. The project is designed to expose the frustrations, anxieties, hopes and fears of everyday people in countries around the world. More specifically, it deals with the fact that the Internet and social media platforms have provided most of the world’s population with a readily available and inexpensive outlet for expressing opinions and expectations on a daily basis. As a result, we live in a world in which expressing ourselves about the challenges we face has perhaps never been easier and yet, it is increasingly difficult to be heard and understood because of the level of “message noise” generated by the quantity of thoughts being simultaneously expressed as a direct result of such ease.

The Choir of Discontent re-contextualises this preoccupying situation in the form of a two-part installation consisting of the single channel video “NOISE” that serves as a thematic introduction to a multilingual interactive video installation composed of walls of video images of persons from different countries who have been asked to express themselves freely and spontaneously (without preparation) on topics related to their frustrations, deceptions and hopes. Individual interviews will rarely be decipherable as programmed waves of simultaneous presentation render them little more than an insignificant component of a wall of unintelligible noise. One or more microphones, video cameras and monitors will be installed to permit the viewing public to contribute their thoughts and feelings live in real time.The interviews with participants from Brazil, Canada, the USA and France have already been completed by video artist collaborators in each of these countries. I am currently trying to organise interviews in Asia and Africa. Hopefully, all of the necessary interviews will be completed in 2025, and post-production can begin in 2026.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a curated promotional platform that offers artists the opportunity to articulate their vision and engage with our diverse international readership through insightful, published dialogues. Conducted by Mohamed Benhadj, founder and curator of Al-Tiba9, these interviews spotlight the artists’ creative journeys and introduce their work to the global contemporary art scene.

Through our extensive network of museums, galleries, art professionals, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide, Al-Tiba9 Interviews provides a meaningful stage for artists to expand their reach and strengthen their presence in the international art discourse.