10 Questions with Angelina Voskopoulos

Angelina Voskopoulou is a multidisciplinary artist whose work traverses sculpture, experimental filmmaking, and screen dance, often exploring themes of human existence, impermanence, and the unseen forces that shape identity. With academic roots in both Fine Arts and Digital Arts, and a teaching role at AKTO College, as well as serving as the author of the Video Art Seminar at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Voskopoulou merges theory with practice in her exploration of materiality, transformation, and the poetic body. Through hybrid forms and ephemeral gestures, her art invites viewers into liminal spaces, where the natural and artificial blur and movement become a site of philosophical inquiry.

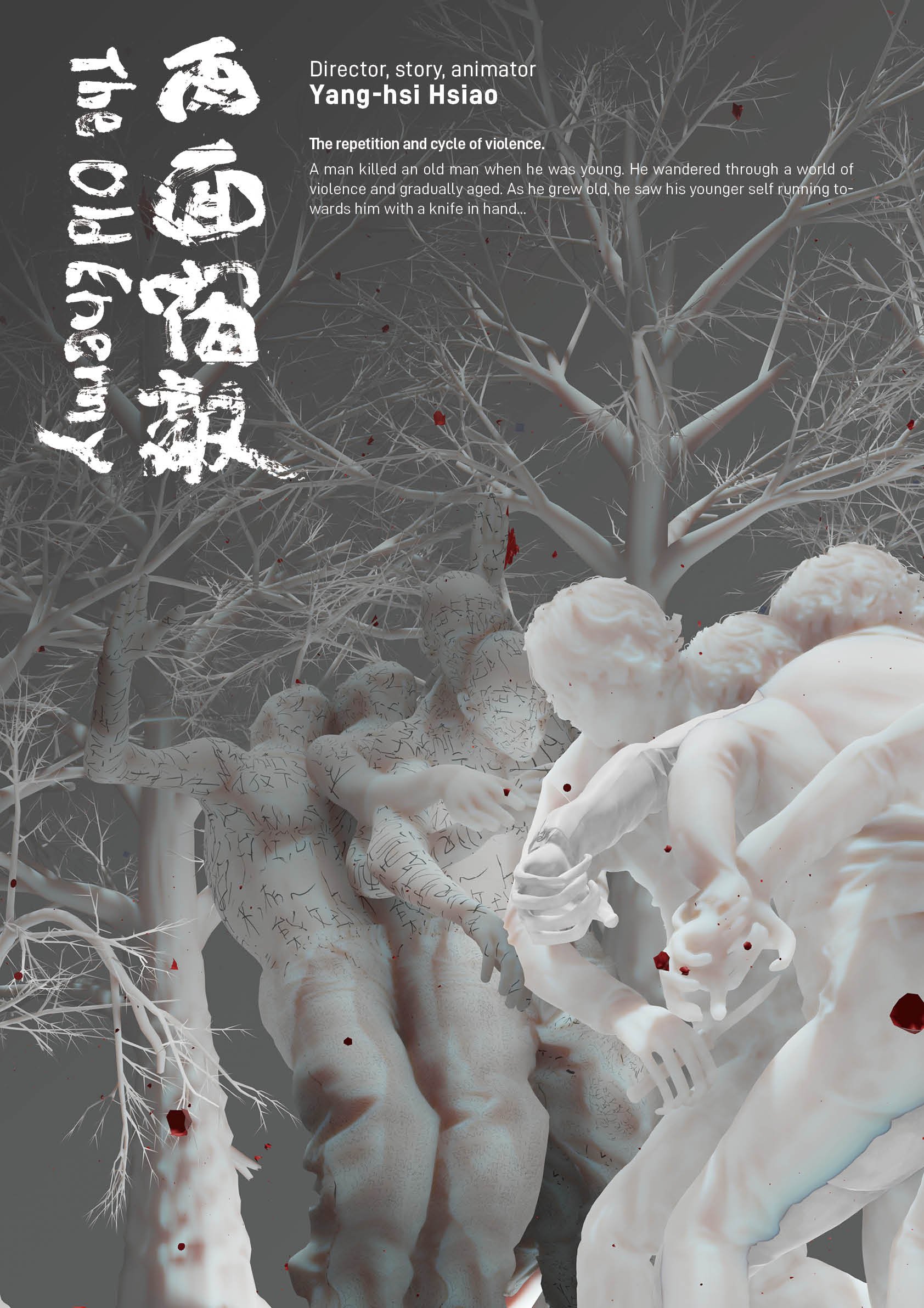

Angelina Voskopoulos - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

My practice unfolds between video art and sculpture, seeking to capture moments of transformation where memory, body, and nature flow into one another. I am drawn to ephemeral states — those delicate passages where identity shifts, desire ignites, and organic matter mutates.

Working with digital media and polyester materials, I create layered narratives that dissolve the boundaries between thehuman, the artificial, and the elemental. In videos like The Seed and Exogenesis, I explore cycles of decay and rebirth, inviting a meditation on the hidden forces shaping existence. In Skin Deep, eros emerges as a vital thread, not only as sensuality, but as the pulse of vulnerability, longing, and embodied memory.

Materiality is central to my approach: the tactile nature of surfaces, both digital and physical, becomes a metaphor for the skin, porous, unstable, alive. Through this process, I seek to create spaces of encounter where viewers can sense transformation as something intimate, emotional, and inevitable.

Ultimately, my work is a continuous dialogue between the visible and the invisible, the organic and the synthetic, the known and the uncertain — an attempt to trace the soft, haunting rhythms of life and loss.

Persephone, Orphic Myth 29, video art, 2023 © Angelina Voskopoulos

INTERVIEW

When did you first become interested in art and develop into the artist you are today?

I was always drawn to forms, textures, and silent gestures—the subtle language of the visual. My interest in art emerged naturally, like a slow-growing vine that wrapped itself around everything I experienced. I didn't grow up thinking I would become an artist, but over time, I realised that creating was not a choice—it was a need. My grandmother, who had Italian roots, was a quiet yet powerful influence; her stories and her poetic way of seeing the world planted early seeds in me. Through time, art became the only language that could fully express the questions I had about human existence, impermanence, and the invisible forces that shape us.

Your academic path blends Fine Arts and Digital Arts across Greece and the UK. How have your studies shaped your multidisciplinary approach to sculpture and video art?

Studying Fine Arts and Technology in Greece, at AKTO College—validated by Middlesex University—offered me a strong foundation in both traditional artistic methods and emerging media. It was a formative period where I started blending materials, experimenting with structure, and thinking about technology not as a tool but as a conceptual extension of the artwork. Later, moving to London for my MA in Digital Arts at the University of the Arts London brought me into contact with a dynamic, international community. London as a city exposed me to new theoretical frameworks and a vibrant network of artists working across disciplines. This academic journey shaped my practice as inherently hybrid, oscillating between the physical and the digital, the sculptural and the cinematic. Teaching sharpens my questions. At AKTO College, I teach post-production, directing, and script principles, and at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, I lead a seminar dedicated to video art. These environments allow me to constantly rethink the language of moving images and how the body, space, and narrative function within them. My experimental filmmaking, often rooted in philosophical inquiry, draws directly from these exchanges. Teaching pushes me to articulate complex, often abstract concepts, and in doing so, I refine my own approach to creation, especially in the way I negotiate theory and practice.

You work across sculpture and video, two mediums largely different. How do they speak to each other in your creative process?

They mirror each other in unexpected ways. My sculptures—ghostly divers made of polyester trapped in transparent cubes—explore absence and presence. They are figures shaped by space, or rather, by the memory of the body. What you see is not the body itself, but the imprint it left behind. This is very close to how I work in video. The camera doesn't simply document—it translates the ephemeral, the vulnerable, the liminal. In both mediums, I seek to approach human existence through poetic absence. Sculpture gives weight to the void; video gives movement to stillness.

Many of your works, such as The Seed and Exogenesis, evoke transformation, decay, and rebirth. What draws you to these cyclical themes, and how do you approach them visually?

I am deeply drawn to cycles—not only of life and death, but of perception, memory, and becoming. The Seed speaks about the origin of things, about energy in potential, while Exogenesis is more cosmological, addressing emergence and the post-human. These works exist between the biological and the metaphysical, where everything is in flux. Visually, I'm drawn to textures that suggest transformation—cracked surfaces, faded colours, slow motion, and overlapping layers that resemble skin, soil, or cosmic dust. The cyclical is not just a theme, it's an atmosphere I try to conjure. Furthermore, in my work, Skin Deep – A Hymn to Eros, love is not an idealised, safe, or stable emotion but a trembling, ephemeral force that is fragile and vulnerable. The video focuses on eros as a constant oscillation between intimacy and disappearance. By using close-up shots and fragmented movements, the work conveys the sensation of love as something unstable, something that resists containment and full comprehension. The body in this piece, much like love itself, flickers between presence and absence, continually reshaping itself in the space between touch and silence.

Another example is in my recent work, The Cat & the Haunting Gospel, which addresses themes of spiritual collapse and post-mortem questioning. The line "Good God is a dead one…" echoes through the work as a reflection on the loss of belief, the fragmentation of sacred narratives, and the haunting residue of what remains after faith dies. It also resonates as a powerful commentary on the political and social decay of systems that once promised salvation but now only serve to perpetuate oppression. Through the haunting play of this phrase in the video, I aim to expose the disintegration of old narratives, forcing us to confront the emptiness of structures that no longer hold meaning. This piece speaks to the larger cycles of societal rebirth—how the political and spiritual landscapes must dissolve before they can be reimagined and rebuilt, free from the ghosts of past power.

The cat in the video becomes a silent observer of a crumbling world, where divine figures are reduced to ghosts, and religious symbols lose their power. In this work, I explore how the collapse of structures—be they religious, social, or personal—can create a space for haunting, for memory, and for transformation.

These works speak to my ongoing inquiry into presence and absence, love and loss, creation and decay. The body, whether in love or in mourning, remains the site of these emotional oscillations, embodying the tension between existence and non-existence. Through these pieces, I strive to capture the delicate, trembling space in between, where the invisible forces of eros and spiritual transformation can be felt, even if they remain out of reach.

You often use polyester for your works. What led you to this material, and how do you see it reflecting the fragility and mutability explored in your practice?

Polyester gives me a paradox: it's both artificial and delicate, synthetic and light-absorbing. I began using it because of its ghostly transparency. The human forms I cast in polyester are not fixed—light and shadow move through them, altering their appearance. This fragility reflects my interest in what can't be held or defined—emotion, breath, memory. The material behaves like a trace, a remainder of something lost or shifting. It lets me sculpt with absence.

In your videos, eros often emerges as a thread linking body, desire, and memory. How do you approach sensuality and vulnerability as artistic materials?

In my work, eros is not merely a theme but an energy, a trembling force that binds the body, desire, and memory. I approach sensuality not as something overt or ornamental, but as a quiet tension that lives in the pauses, in unfinished gestures, in the way movement breathes. Sensuality and vulnerability are artistic materials that I treat with care, almost like fragile elements that carry emotional weight. They are never about spectacle. They are about resonance—what remains after the touch, after the gaze.

Vulnerability, to me, is as sculptural as flesh. It's where the body opens, where control dissolves, where transformation begins. I often work with close-up shots, fragmented choreography, and gestures that appear and vanish in the same breath. This approach allows space for the unseen, the unsaid, for what exists only as sensation or memory. Desire, in this context, is not linear. It's a flicker, a broken breath, a space where the body remembers, longs, and simultaneously disappears.

In Skin Deep – A Hymn to Eros, I explored love not as a stable or idealised force, but as a fragile, flickering intensity—something always at the edge of disappearance. The work uses close, fragmented imagery to evoke eros as oscillation: between intimacy and distance, between presence and absence. The body becomes a site of vulnerability, constantly reshaping itself within the fragile space of love.

Similarly, Behind This Page but Not Disappearing navigates the tension between revealing and hiding, between exposure and withdrawal. It reflects on the thresholds of being seen and being lost—how desire, memory, and selfhood exist in layered, shifting states. In both works, I am drawn to that in-between space where the emotional and the ephemeral converge—where eros is not something to be captured, but something to be felt through what remains unsaid.

Exogenesis trilogy, Biennale Malta, 2015 © Angelina Voskopoulos

You've participated in unique, site-specific performances, like Europass and the Levante Jazz Festival, where sound, space, and video converge. How do these live, collaborative environments expand your artistic vision?

These collaborations are moments of living dialogue. In Europass, projecting video onto abandoned ships and boats in Eleusis created a mythic, almost ritualistic space where decay met mythology. At the Levante Jazz Festival, improvisation between live music and moving images allowed for a kind of breathing artwork that unfolded in real time. These environments pull me out of the solitude of the studio and invite chance, resonance, and risk. They remind me that the artwork is not an object, but a situation.

Whether working with digital imagery or sculptural surfaces, your practice explores the boundaries between natural and artificial. How do you perceive this relationship evolving in your future work?

I see the boundary between the natural and the artificial not as a rigid line but as a fluid space—a threshold where the two weave together like light and shadow, like breath and memory. In my future work, I envision this relationship continuing to blur and oscillate. The digital, once cold and mechanical, is becoming more intimate, more fragile, as it breathes with the weight of organic material, like the polyester forms I cast, light and transparent, as if caught between worlds. The artificial becomes a living thing, porous and open to transformation, while the natural no longer feels fixed, but rather as something that evolves, decays, and reappears. These elements—digital, sculptural, organic—will continue to converse, merge, and dissolve into each other, creating spaces where the distinctions of origin no longer matter, where existence itself is a continual dance of becoming. In this future, I see technology not as something that opposes nature, but as something that allows us to perceive it anew, to stretch its meaning, and to confront its mysteries with a deeper sense of wonder.

CINEMA ITALIANO DELLA MOSTRA INTERNAZIONALE DEL NUOVO, 2012 © Angelina Voskopoulos

MDINA - Cathedral, Biennale Malta, 2024 © Angelina Voskopoulos

Your recent projects suggest a growing interest in narrative and speculative forms. What's next for you creatively? Any new mediums, stories, or concepts you're excited to explore?

I feel drawn to hybrid forms of speculative narrative—experimental film pieces that combine personal mythology, philosophical fiction, and embodied movement. I'm currently developing a new body of work inspired by the figure of the angel as a threshold-being, a metaphor for inner transition, spiritual metamorphosis, and existential dislocation. These pieces will continue to blend screen dance and experimental film, allowing the camera to move as a witness of bothcorporeal and metaphysical transformation.

Lastly, what is your most significant project for 2025? Do you have something underway that you want to share with our readers?

In 2025, I will embark on an exploration of the angel as a threshold figure—a being suspended between worlds, neither fully here nor there. This project is less about defining existence and more about its dissolution, its subtle passage from presence to absence. Through the lens of movement and cinema, I hope to capture that fleeting moment before the body becomes a shadow—when it is neither alive nor dead, neither visible nor invisible. It is a meditation on what vanishes just as we begin to grasp it. The choreography, born from the pulse of internal states rather than external forms, will move like a whisper, delicate, ephemeral. I want to explore the space between what we can touch and what slips through our fingers, to dissolve the lines between the real and the unseen. In this work, the ineffable becomes tangible only in its absence, as a kind of presence that fades the moment it is recognised. It is a pursuit of what lives, and dies, in the space of the unspoken. The Angel isn't just a figure of transition, but also a kind of image-ghost. The phantasmal element as the return of something that's absent—something that's never fully present but still haunts the present moment In this sense, the Angel can be seen as a ghostly image that brings together the "already dead" and the "still living" within film or dance. When we look at photographic or cinematic images, they share this phantasmal quality. There's always a trace of something that's already passed. When these images are distorted, slowed down, blurred, or stripped of narrative context, they act just like an Angel—they come back as memories, trauma, or a denial of completeness. Tarkovsky, for instance, through his idea of the "sculpture of time," looks at the Angel's ghost not as a metaphysical being, but as a function of the camera and the poetic unpredictability of the image. In films like Nostalgia or Stalker, the body exists in between the world and the non-world, moving through spaces that are full of silence and decay, almost as if these spaces are inhabited by ghosts. In Wim Wenders' Wings of Desire, the Angel is an observer. The camera becomes the Angel's eyes, drifting between moments of human loneliness. The use of black and white versus colour is not just an aesthetic choice, but a sign of perspective shifting—from the Angel to the human and back again. The ghostly quality here is tied to the Angel's longing to feel, to the trauma of not participating, of quietly watching from the outside.

In my own work, the Angel shows up as a rupture in the movement. The camera focuses not only on human bodies, but also on traces, abandoned spaces, skin details, wrinkles, shadows, and subtle movements. The body doesn't "dance" in the usual sense; it moves through an inner vibration, almost as if something invisible is guiding it. This is a Butoh body—abody that "doesn't want to express itself but to dig up the grave it carries inside" (Hijikata, 1968). The phantasmal Angel,as an aesthetic concept, introduces an in-between space, collapsing the boundaries between life and death, presence and absence. This in-between state doesn't allow for clear separation or stability, but emphasises the continuous flow of existence. The Angel, as a ghost, is never entirely absent but always present in its absence, creating a tension that keeps the normal flow of things in suspension. The space around the Angel becomes charged with the feeling that something "remains," yet can never fully be attained. In contemporary art, this phantasmal element refers to a world where the past is never fully separate from the present. It's the forms that haven't fully died but haven't fully lived either. In the image, this coexistence reshapes our perception of time, making the sense of loss and mourning palpable through an image that's"faded" from its original state. So, the Angel isn't just a metaphysical figure, and it's an image that holds the imprint of the past. In film or dance, the image has the power to bring that ghost back, either through slow, repetitive movements or by not being fully captured in the normal flow of time. The phantasmal Angel brings up this idea of uncertainty, memory, and undefined existence. Even though it's a temporary and elusive presence, it occupies a space within the image that's charged with the feeling of something impossible and unattainable.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.