10 Questions with Rhea Hu

Rhea Hu (b. 1998, China) is an illustrator and visual storyteller pursuing an MFA in Illustration at the Rhode Island School of Design. With a background in Traditional Chinese Medicine (B.S., Shanghai, 2021), her interdisciplinary practice spans drawing, digital fabrication, and book arts. Hu has exhibited at ISB Gallery’s AS WE ARE Pride Show (2025) and Digitalis corpus at RISD (2024), and has presented work at Unbound 2025 and SI MoCCA Arts Fest. Her publications include A Gift from Bubu (Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2014) and co-authorship of ascientometric study in Medicine (2021). She currently works as a Graduate Assistant in Special Collections and a Teaching Assistant in Figure Drawing at RISD.

Rhea Hu - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Rhea Hu is a visual storytelling artist currently pursuing an MFA in Illustration at the Rhode Island School of Design. Her practice centres on illustration, graphic design, and bookmaking. Working with materials such as pencil, charcoal, pastel, and acrylic, she creates cohesive narrative sequences through zines, artist books, and poster series. By assigning symbolic meaning to everyday objects and composing images with structural clarity, Hu constructs visual languages that are distilled and deliberate, infused with quiet tension, poetic precision, and moments of irony.

Influenced by literature and visual activism, her work explores the friction between personal memory and collective systems of power, transforming private experiences into narratives that resonate on a broader cultural level.

The Dream of Cloth Fish, Accordion fold picture book, eyeshadow paste, crayon, collage, 4x6 in, 18 pages, 2025 © Rhea Hu

INTERVIEW

Please introduce yourself to our readers. Who are you, and how did you become the artist you are today?

Hello, I'm Rhea Hu. I find interviews fascinating; it feels like the most essential parts of a finished dish in a recipe. Talking about myself can be quite self-centred, not that I dislike it, but I try to avoid being too aware that I'm doing it.

I decided to study Traditional Chinese Medicine for undergrad, trying to prove that, as someone truly gifted, I could balance both creativity and practical life. During that time, I conducted countless experiments that ended with the killing of lab animals. It forced me to confront questions about animal ethics and the abuse of power under human-centred chauvinism, extending to broader issues of systemic oppression. These questions gradually led me away from the framework of science, while I found that art thrives in these grey zones, with a freedom and authority of its own. This journey leads me to use my practice as a way of reflection, investigation and retelling of how power operates across systems and within personal experience.

The Dream of Cloth Fish, Accordion fold picture book, eyeshadow paste, crayon, collage, 4x6 in, 18 pages, 2025 © Rhea Hu

You first studied Traditional Chinese Medicine before pursuing an MFA in Illustration at RISD. How did this transition come about, and how do these two worlds continue to influence your artistic practice?

Traditional Chinese Medicine is controversially considered a quasi-science, a Latin-derived combining form and adjective meaning "almost", while illustration is historically considered a quasi-art. The question isn't about what the threshold of quasi was, but how we define modernity and advancement. I went through a period of deeply negative feelings toward TCM, not toward itself, but toward how systematic frameworks attempt to mask the sense of fragmentation that comes with complex, organic bodies of knowledge. Our society and academic institutions have placed it under the scrutiny of modern medical systems, simultaneously resisting TCM's own philosophical framework while desperately hoping to completely decode and interpret its inner mechanisms through "modern," which is to say Western, approaches. Mystery, enigma, and magic needed to be put down in pragmatism. But for me, for instance, you need to respect mysteries as mysteries, allow enigmas to remain enigmatic. My undergraduate science degree taught me that sometimes you mustacknowledge the limitations of modern science. Human knowledge remains incomplete, which is why the intersection of faith and science, where facts coexist with traces of myth and imagination, is so compelling.

You work with pencil, charcoal, pastel, and acrylic, as well as digital fabrication and book arts. How do you choose which medium to use for a project, and what do you enjoy most about this variety?

I love challenges. Maria Callas once said, "When you perform, half of the brain has to be in complete control and the other half of the brain has to be at a complete loss." This also applies to my work. However, the difficulty I experience during creation is often that 'complete control' part, wrestling with materials, grappling with concepts, and entangled with my own perfectionism. I can't let go, I can't lose control by myself, but I still want to do something that is so punishing and so difficult. In terms of materials, this manifests as my constant search for unfamiliar media. I retain the arrogance and playfulness of the self-learner. When switching materials, their physical properties change your working method. Pencil feels like conducting an orchestra, gradual accumulation and progression. Ink is dance, rhythm and exhaustion extending through my limbs. I believe that mediums shape one's character, and through working across diverse mediums, I can reach the integrity of my artist persona.

A Thousand Plateaus, digital print on rice paper, 12x153 cm, 2025 © Rhea Hu

A Thousand Plateaus, digital print on rice paper, 12x153 cm, 2025 © Rhea Hu

As an illustrator and visual storyteller, what does narrative mean to you, and how do you build stories through images rather than words?

Everything is about words. I believe those who possess words also possess the world language, which implies what narrative means to me; it is all about implication. My mother tongue has been castrated in this generation, while English as a second language only intensifies this alienation. Censorship, self-censorship, and the untranslatable, all these obstacles have pushed me into an expression that relies on implying a lot by using fragmented text, images, and sequences. It's become something like an indecipherable, multiply-encoded secret passage, almost a cunning game. Metanarratives, or in a more general and simplified way, ideology, do not speak for me. My work serves no one else; I work only for myself. I must speak for myself to avoid feeling powerless. I like to unfold stories through sequences of wordless images. I believe images can transcend language barriers, though paradoxically, my images are usually distilledfrom vast amounts of text.

Artist books and zines play an important role in your work. What draws you to the book form as a space for storytelling?

I've had a strong connection to books since childhood. When I was young, my mother loved playing mahjong and would leave me alone in bookstores so we didn't need a nanny. So I read everything, literature, fairy tales, horror novels, cookbooks, beauty magazines, and comics. I liked opening books from the middle or back, reading a few sentences, then deciding whether to start from the beginning. For me, a good book is one that's engaging from any starting point.

I remember in Duras's The Lover, she recalls a happy moment from family life during spring cleaning, the floor covered in soapy water while her mother played the piano. Her intense reverence for that memory reveals her longing for refinement, cleanliness, joy, elegance, and a happy family life. She is destined to step on that path of chasing fragile dignity and a romanticised, extraordinary life.

Every word and sentence belongs to, is enslaved by, and is devoted to the story, while simultaneously being irreplaceable, indispensable components of that story. This desire for wholeness and consistency is something I carry throughout my bookmaking and zine work. I have strict self-editing tendencies and endlessly refine the reading experience, but I don't want my audience to notice this. I want them to be like ten-year-old me, opening from the middle, then deciding to start from the beginning.

A Thousand Plateaus, digital print on rice paper, 12x153 cm, 2025 © Rhea Hu

You often assign symbolic meaning to simple objects in your illustrations. Could you share an example of how an ordinary element became central to a narrative in your work?

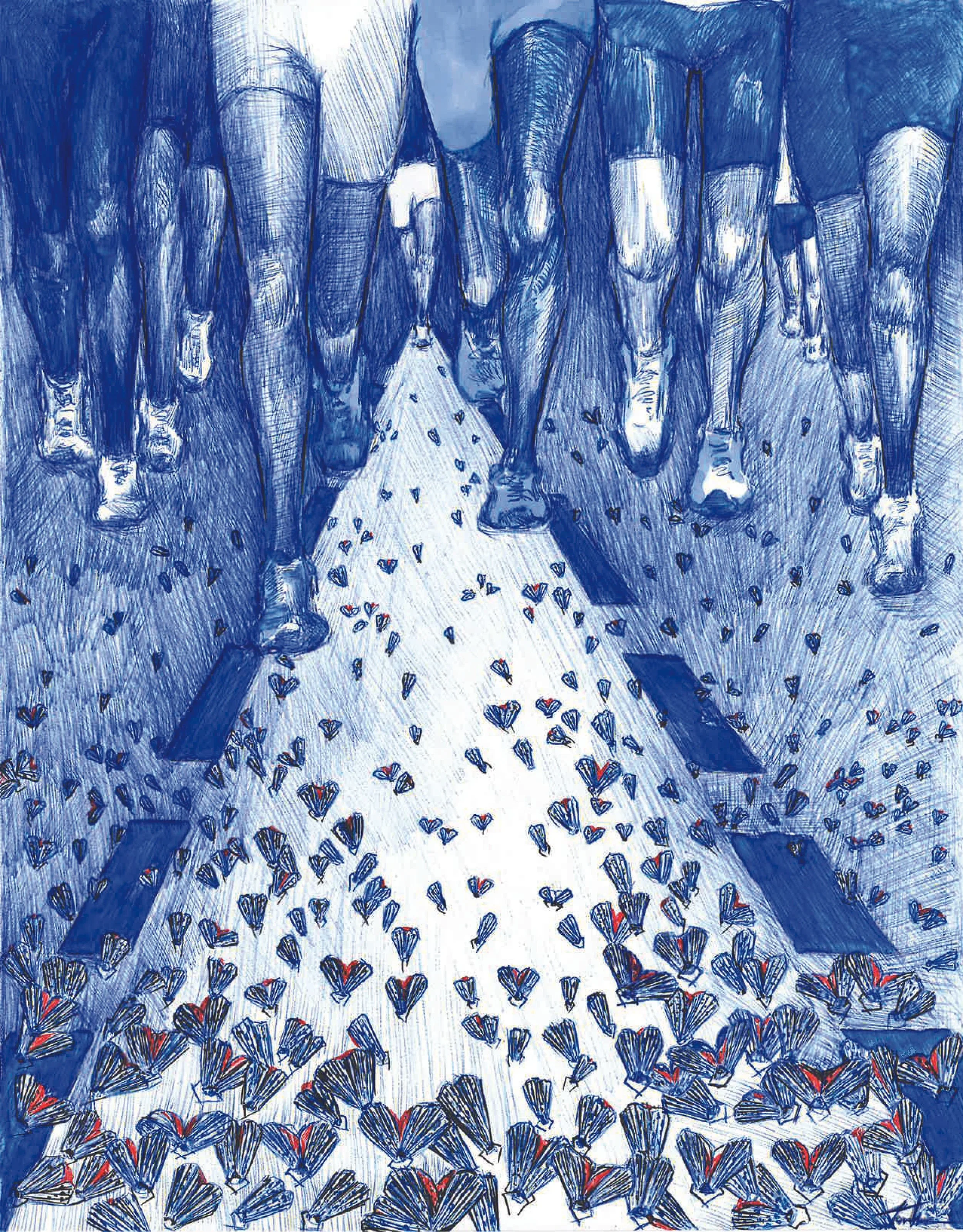

I try to use simple imagery to address complex subjects such as war, exile, death, and authoritarian regimes. Working in this way is more ethical and fun to execute. Take my work "The King Bows, The King Kills", which draws from Romanian exile writer Herta Müller's essay collection. I selected one of her poems:

"In the corner house, the patrol

Pushes someone off the balcony there,

Over the elderberry,

Then it was again suicide.

In the paper house resides the statement."

Müller evokes the violent erasure of intellectuals, civilians, and dissidents, forced suicides, disappearances, and the bureaucratic normalisation of state violence. I used uniforms to represent the uniformity and dehumanisation of violent enforcers. A uniform is built from recognisable components such as its cut, rigid form, belts, insignia, and other standardised details. People respond instinctively to these symbols. While the ones I depict are not historically accurate Romanian police uniforms, they point to a broader truth: under authoritarian regimes, violence is both concealed and expressed through the sameness of uniforms, a universal form of brutality.

Simultaneously, I used clothing to represent civilians stripped of power, dignity, and livelihood during political upheaval. But their clothes differ in size, fabric, and style, and they're piled pathetically on carts like garbage. I want to suggest that the universal stripping of individuality is the very essence of dictatorship.

Your practice engages with memory, literature, and systems of power. How do you navigate the balance between personal experience and broader cultural or political narratives?

I won't do that. And I question why it should be assumed as necessary. In the process of creating, I don't think about my role or responsibility as an artist.

Unwomanly Face of War, Digital illustration, 5000x3200 pixel, 8 pages, 2023 © Rhea Hu

Unwomanly Face of War, Digital illustration, 5000x3200 pixel, 8 pages, 2023 © Rhea Hu

Who or what are your main sources of inspiration, whether artists, writers, or everyday encounters?

I have this notebook that records basically everything: conversations, doodles, contact info, first draft of my short story and long projects. I collect these things. This summer, I had a conversation with a Vietnamese poet and educator, Vi Ki Nao, and book artist Janine Wong. It was a four-hour-long conversation. The way they described their creative process was absolutely mind-blowing. Vi told me she writes at least three hours a day, producing two hundred pages, then selects three of them to submit to the publisher, and she always gets accepted. I asked how they knew whether their work was good or not. She said: Try to imagine reading it aloud in front of an audience, would you feel confident?

JW suggested that we should collaborate, and added that collaboration itself is such a profoundly feminine thing. I recorded the whole exchange in my notebook, sketching their words into different shapes, straight lines, curves, circles, and bursts. JW's husband arrived and asked if she had completely forgotten about her afternoon whale-watching trip. She told him, "We are seduced by education."

It was such a beautiful moment. You can't let these moments slip away. Don't assume that once they appear, they can simply happen again. Their methods of working and their philosophy of life continue to influence me even now. Memory is so unreliable; if I don't write these things down, it's as if they never happened.

But let's return to the matter of inspiration. I think we've become too used to seeing the final product; they are smooth and natural, as if no effort. Now, when I read a beautiful poem, I remind myself that the poet must have gone through countless rounds of self-editing, that behind it there were maybe two hundred drafts. Perhaps there isn't actually so much "inspiration" in the world after all, maybe creation is a far fairer realm than we tend to imagine.

You are a Teaching Assistant in figure drawing and a Graduate Assistant in Special Collections. How do these roles feed back into your own creative process?

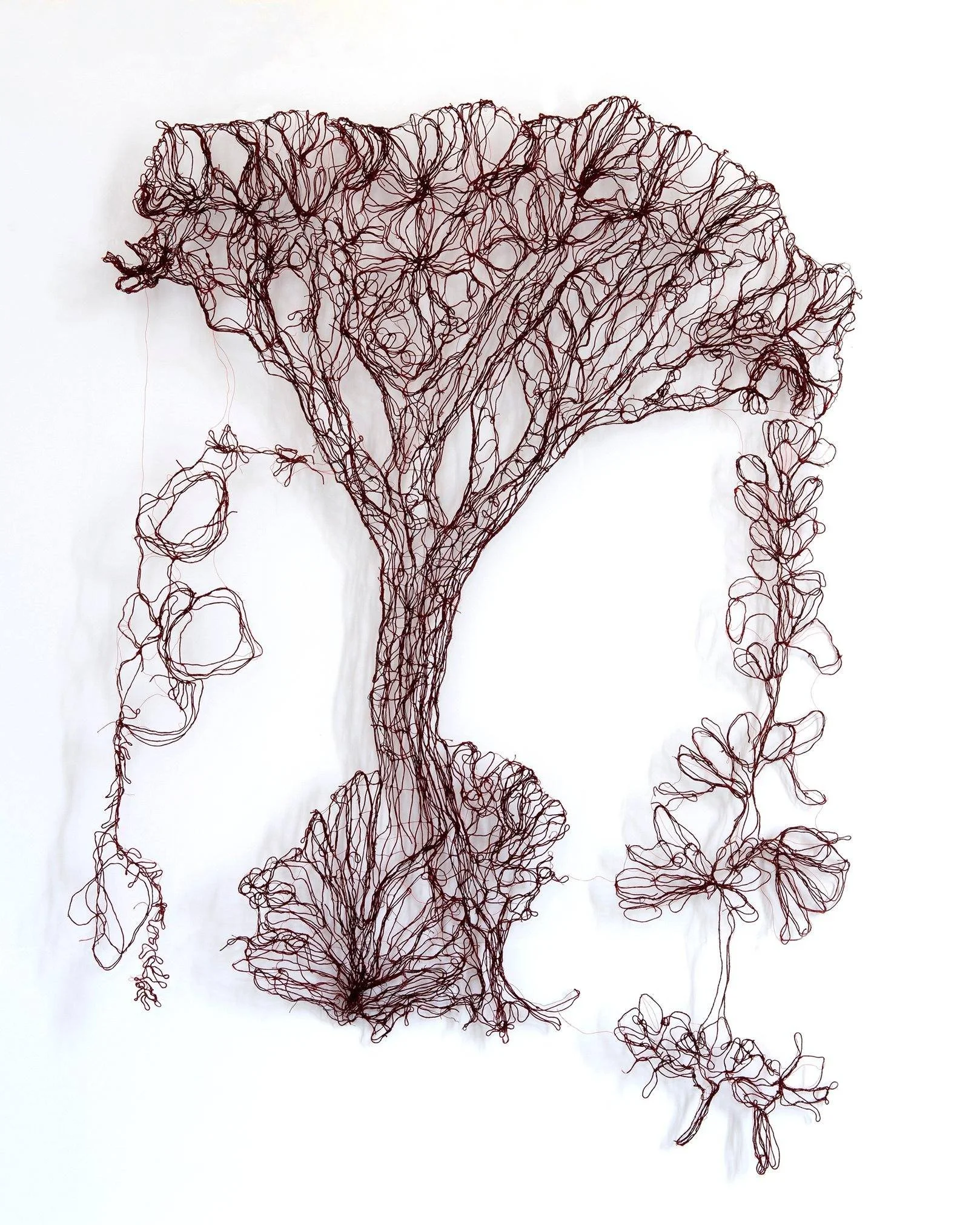

I think what I spend most time doing in both positions is observing. Especially in special collections work, I have a blind love for books. At the moment, I am processing a large donation of materials from Cranston Print Works. The workinvolves piles of fabric samples and ledgers, and it requires putting aside personal opinion. I've been training myself to describe these materials with clarity and neutrality, producing systematic guides that can serve future researchers.

Stay Awhile, Saddle stitching zine, inkjet prints, pencil on watercolor paper, 4×5 in, 20 pages, 2025 © Rhea Hu

You've recently exhibited at shows such as AS WE ARE and Digitalis corpus. What ideas or questions were you exploring in these projects?

At Digitalis corpus, I exhibited a 3D-printed sculpture in progress alongside a projection of edited screen recordings of my modelling process. This project was less about mastering new techniques than about learning a kind of computer logic, as a language of its own. It's training me to think and build in its own way. Whenever I tried to rely on human intuition, I ran into obstacles; it was a one-way communication. Also, though I'm not a religious person, I found myself praying throughout the process of auto-repair. What's funny is how easily I started treating the machine like some higher power. While the process of digital fabrication also mirrors the artist's fixation on the digital object, the way technology seduces us into endless self-scrutiny, the scanner's mechanism, as thousands of photos pieced together, contains infinite acts of gazing, and the whole process serves a solemn purpose. Ultimately, this work led me to reflect on the hidden labour within digital processes and on how technology cultivates a fetish for flawless virtual forms.

Lastly, what directions or projects are you most excited to pursue after your MFA, and how do you envision your practice evolving in the future?

I'm currently working on a collaborative project with the AAPI History Museum, hoping to bring a different perspective as an emerging female artist and Chinese immigrant. I want to use my visual strategies to retell the often obscured and overlooked histories, personal memories, and collective recollections of East Asian immigrants in America. Also, I hope to have more opportunities in the future to combine science, Traditional Chinese Medicine, art, and my cultural background to explore questions like: What kinds of knowledge/practices/histories get marginalised? Why does knowledge from the margins often better capture complexity?

Artist’s Talk

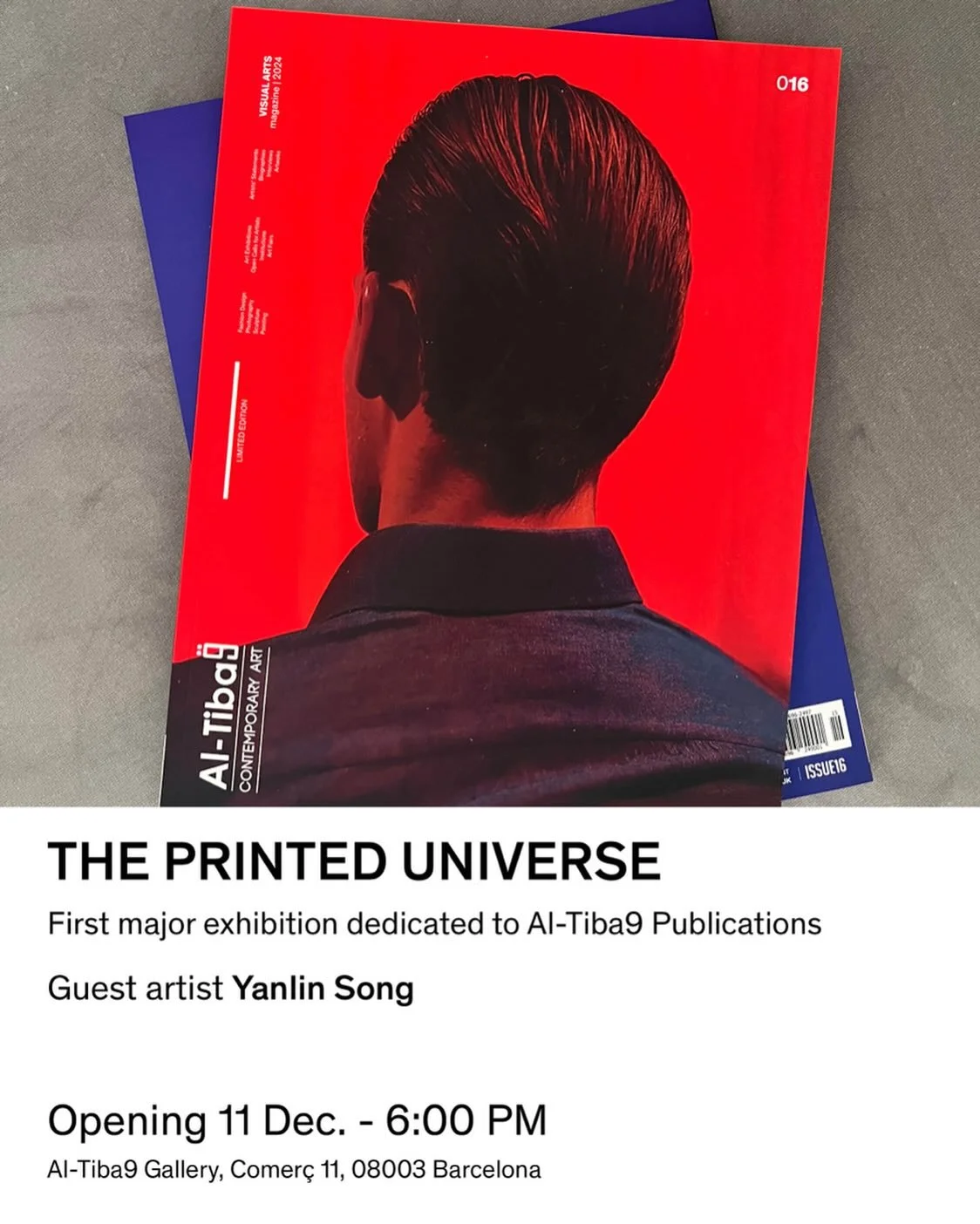

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a curated promotional platform that offers artists the opportunity to articulate their vision and engage with our diverse international readership through insightful, published dialogues. Conducted by Mohamed Benhadj, founder and curator of Al-Tiba9, these interviews spotlight the artists’ creative journeys and introduce their work to the global contemporary art scene.

Through our extensive network of museums, galleries, art professionals, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide, Al-Tiba9 Interviews provides a meaningful stage for artists to expand their reach and strengthen their presence in the international art discourse.