10 Questions with Artem Mayer

Artem Mayer (b. 1989) is a guitar maker and contemporary artist based in Moscow, Russia. He graduated from Moscow University of Economics, Statistics and Informatics in 2011 and

completed music school in 2008, but his path in instrument making began earlier and grew from an obsession rather than formal training. After seeing a magazine photo of a Slipknot guitarist holding a B.C. Rich Warlock, Mayer became fascinated by the idea that a guitar could be a sculptural object as much as a musical tool. His earliest attempts were hands-on and improvised; at one point, he even tried to build a guitar by cutting up an old door, before completing his first full instrument in 2006.

In 2012, he founded Copper Guitars, where he builds custom instruments for musicians and

collectors and also undertakes repair, refinishing, and restoration of vintage instruments from major brands. Alongside commissions, Mayer creates independent concept builds as an artistic practice, among them the Donut guitar, French fries guitar, iCaster and Instant noodles guitar. His projects have received broad coverage across music, art, and technology outlets, including reviews by multiple well-known creators and features in print art magazines; the Donut guitar was also shown on a Times Square billboard.

Artem Mayer - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Artem Mayer is a contemporary artist and guitar maker whose work sits between luthiery and contemporary art. His practice is guided by a simple principle: he makes what he personally wants to make and what gives him genuine enjoyment. If the result resonates with others, that is a welcome outcome, but not the starting point.

Mayer treats the electric guitar as both a musical tool and a sculptural object, equal parts sound, design, and story. For him, playability is non-negotiable: an object that cannot be played fails to meet the full purpose of a guitar, no matter how strong the concept is. This is why his concept instruments are built to be fully functional, even when they resemble things we usually consume or scroll past, such as instant noodles, smartphones, French fries, donuts.

Mayer moves freely between custom commissions and independent concept instruments. He is drawn to pop culture and to everyday visual language, but his themes are not fixed; they change with mood, context, and memory, and can include personal references such as childhood associations. The form may be humorous or direct, but the intent remains consistent: to expand what a guitar can be, without separating design from sound.

Trained through music education and an economics background, Mayer is drawn to the tension between rational structure and irrational desire: the engineering discipline required to build a reliable instrument versus the impulse-driven attachment people form to objects, brands, and images. Consumer culture offers comfort and identity through things that are often treated as disposable. By exaggerating these objects and turning them into guitars, he asks whether something perceived as temporary can become precious, carefully played, maintained, and cared for.

Humour is often the entry point. A “donut” or “noodles” guitar may make someone smile first, but once it is picked up, the viewer meets wood, weight, resonance, and technical detail. Mayer aims for that shift, from joke to instrument, from meme-like recognition to an intimate, physical experience. Materials and techniques are chosen by necessity rather than tradition: wood is central to much of his work, but he has no fixed limits, and will learn new methods when a project requires them. Influenced by pop art, particularly Andy Warhol’s focus on mass culture and the status of objects, Mayer uses the guitar format to test where craftsmanship ends and contemporary art begins.

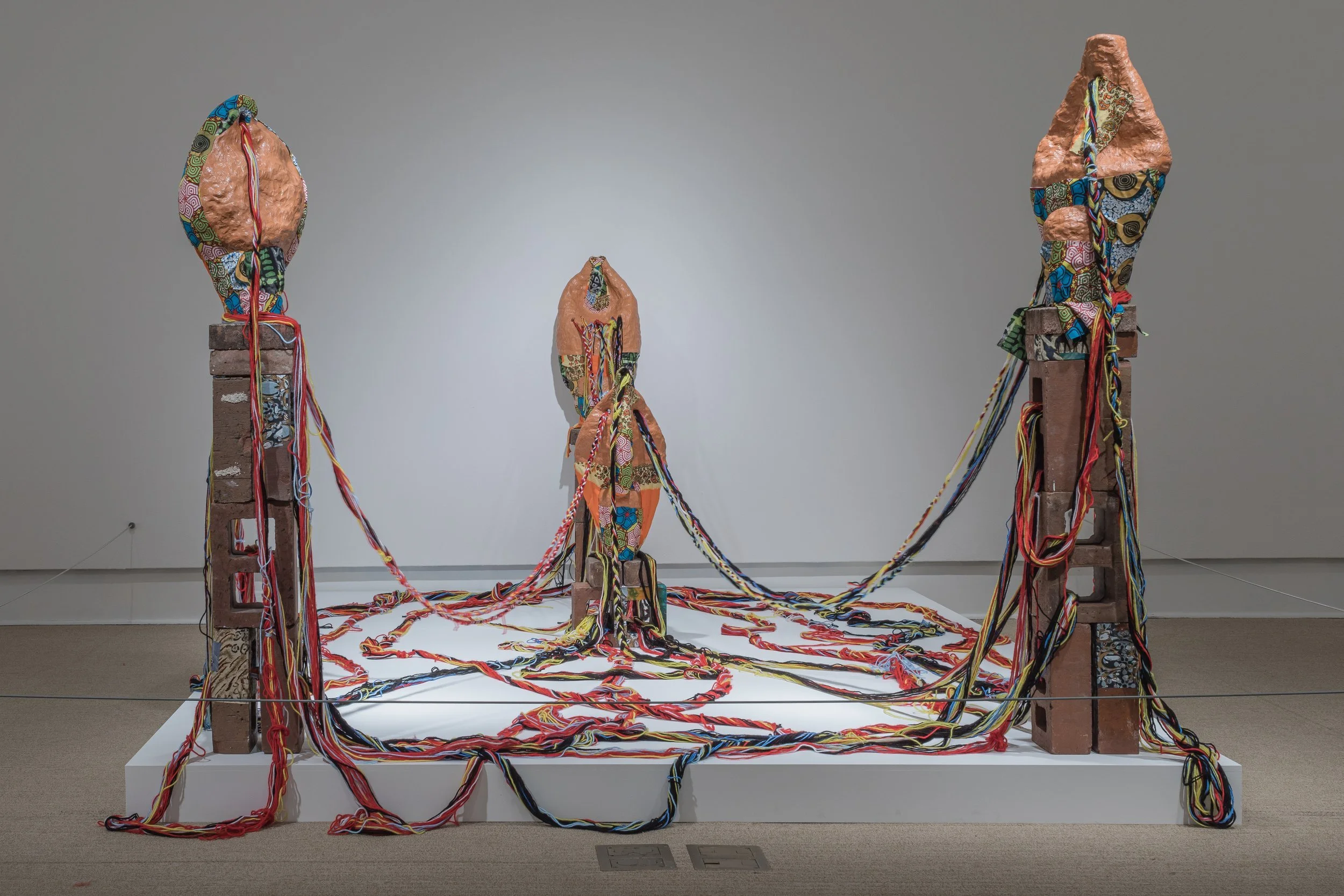

X-ray guitars, 2024 © Artem Mayer

INTERVIEW

Let’s start from the beginning. When did you first become interested in art and making things, and what sparked your fascination with guitars?

If I go back to the very beginning, my mother was the one who introduced me to art. At home, we had a book with reproductions of Vasily Polenov’s paintings, and as a child, I could look at those images for a very long time. I think that’s where the feeling started that visual things can completely pull you in.

At the same time, I loved LEGO and all kinds of technical construction sets. I was always drawn not just to looking at objects, but to taking them apart, putting them together and inventing my own constructions.

And then the guitar happened. One day, I saw a photo in a magazine of Slipknot’s guitarist with his B.C. Rich Warlock, and that guitar just blew my mind. It was a shock: an instrument could look like that, not only like a “classical” guitar. I decided I wanted to do something like that myself.

My first attempt to make a guitar was very improvised; I decided to cut it out of an old door. That didn’t work out at all: the door turned out to be hollow inside. Then there were attempts in a friend’s garage. His father built custom kitchens, so he had all the tools you could dream of. I remember it was winter, and I decided that I could simply saw a young tree trunk in half and use that as a neck. Of course, that didn’t work either, but the attempt itself taught me a lot.

My first “finished” guitar was red, with a white painted pickguard. At the time, I thought pickguards were painted on, not cut from plastic. My first acoustic guitar, I also basically had to make for myself: I got a very worn-out instrument, and to make it playable at all, I rebuilt the back and changed a lot in the construction. So from the very beginning, my interest in guitars was tied not only to owning them, but to reworking, rethinking and building them.

You did not follow a traditional path in instrument making. Which experiences were most important in developing your practice?

My path is both traditional and non-traditional at the same time. I didn’t go through a classical school in the sense of formal education, but in terms of sheer volume, it’s a very traditional route: I’ve built and repaired a huge number of guitars and done a lot of modification work.

I believe that to do something non-traditional, you first have to do a lot of traditional work. You can’t meaningfully break or bend the rules of a genre if you don’t understand that genre as a specialist. First, you learn the rules, and only then can you allow yourself to move away from them.

Every guitar I’ve built or repaired has given me experience: how wood behaves, how different constructions affect sound and reliability, how people actually use their instruments. That’s the foundation.

My first truly “unusual” work was the instant noodles guitar. That’s where the line began that people most often notice now: conceptual, pop-art instruments. But without many years of running a “normal” workshop, repairs, custom builds, and fine-tuning standard guitars, it simply wouldn’t be possible to do those projects at a high level.

How did your background in music and economics shape the way you approach guitar making today?

My musical education gave me the most important thing: a sense of the instrument from the player’s side. I’ve always loved playing guitar, and at some point, it became clear: if I want to play properly, I need a proper instrument, which means I’ll have to build it myself. In Rybinsk, where I lived then, there were practically no luthiers, and the guitars I could find were far from ideal. I literally had to build an instrument for myself.

My education in economics helps in a different way. It gave me an understanding that a workshop is not only creativity, but also a business. I do both repair and building. I have a workshop, clients, and processes. You have to communicate with people, calculate, plan, and be an entrepreneur. For me, business is also a form of creativity: you can not only create an artwork, but also build a sustainable system around it, jobs, a working environment, and a community.

At the same time, I’m sceptical about education when it turns into a set of rigid frames: people tell you “how things are done”, and you stop looking for your own paths. In situations where a person with a classical specialized education thinks “this isn’t done”, a self-taught person has a chance to ask: “Why not try?” When you don’t see the frame, you don’t “know” that something is impossible, and you start figuring out how to make it real. That’s how breakthroughs and true discoveries happen.

Donut guitar, back side, 2025 © Artem Mayer

Donut guitar, 2025 © Artem Mayer

Why did you choose the electric guitar as your main medium rather than treating it only as a musical tool?

I see the electric guitar as an object that already exists at the intersection of art and everyday life. We have designer sofas, chairs, and lamps; no one is surprised that they are both utilitarian objects and pieces of design. Why shouldn’t a guitar belong to the same category?

A guitar is a tool of production in art: it’s how sound enters the world. In that sense, it’s no less worthy of being seen as art than a painting or a sculptural object. Especially when we talk about pop art and mass culture. A soup can on its own is just a can of soup, but in a certain context, it becomes a symbol of its time.

The electric guitar is historically connected with rock, pop culture and mass imagery. For me, it’s logical to use it as a medium: it’s a recognisable, universally understood object that can be reinterpreted and turned into a statement. I don’t separate “musical instrument” and “art object” too strictly; in my work, they are one and the same.

How do you decide whether a project becomes a commissioned instrument or an independent concept build?

I don’t really “decide” this directly. Everything starts with an idea. When a concept appears that needs maximum creative space, it will most likely become an independent art project.

The “normal” guitars, in the best sense of the word, are custom instruments for musicians and are built on commission: there is a specific person, specific tasks for sound, ergonomics, and budget. That’s a separate line of work.

Concept and project guitars appear when I feel a need to say something. First comes the image and the meaning behind it, and only then the realization.

Can you describe your creative process, from the first idea to a finished, playable guitar?

As I already mentioned, for me, everything starts with an idea. An idea is not “let’s pour epoxy over noodles”. That’s a method. An idea is what this action will stand for, what you want to express through the object, which symbol you choose and how you interpret it. Meaning comes first, technique second.

Once the visual image has formed in my head, I start thinking about realisation: which materials are appropriate, what visual language it should use, and how far I can push the form without killing the instrument’s functionality. At this stage, I work out the construction: how the weight will be distributed, which characteristics are critical, what has to remain “classic” and where I can allow myself to experiment.

Sometimes I discuss ideas with people around me, friends, and assistants. I’m surrounded by many talented people, and when I share an idea, I often hear questions or observations in response that help refine it or reveal weak spots.

Then the actual production begins: experiments with how to realize the idea, preparing blanks, assembly, shaping, finishing, electronics, and setup. At the final stage, we often test the instrument with musician friends: they come to play it, try it out, and we shoot video. So the final chord of the project is not only mine, it’s shared.

Many of your works reference everyday objects and pop culture. What draws you to these themes?

It’s simply the time we live in. Pop culture is called “pop” because it’s everywhere around us, from packaging in the supermarket to our phone screens. I live inside this environment; I’m a contemporary of this world, and it’s natural that my art is contemporary in that sense too.

For Monet, his “contemporary” was boulevards, trains, people around him. For us, it’s instant noodles, smartphones, fast food, and media. What we see around us every day inevitably shapes and inspires us. I’m not trying to escape that; on the contrary, I take these images and reinterpret them through the form of a guitar.

I’m interested in how an object that is usually seen as disposable, food, packaging, or gadgets, can turn into something people treat carefully, tune, protect, and store. It’s a way to talk about our culture of consumption in a language that is natural for me: the language of a musical instrument.

iCaster, 2020 © Artem Mayer

Pissed mattress bass, 2025 © Artem Mayer

iCaster, 2020 © Artem Mayer

Pissed mattress bass, 2025 © Artem Mayer

How have musicians, collectors, and audiences responded to your concept guitars?

If I simplify and leave a bit of self-irony, I could say: 90% of people don’t care, 10% hate me and wish I’d fail. But that’s a joke. In reality, the response is mostly very positive. People enjoy it when something is both familiar and completely unexpected. With the Donut Guitar, for example, I see how people come specifically just to look at it and take a photo, even if they don’t plan to buy or order anything. It makes them smile, sparks curiosity and questions.

Musicians and collectors usually start with the visual reaction, “what kind of madness is this?” and then they look closer at the details: the construction, the workmanship, the sound. And when it becomes clear that it’s not just an image but also a serious instrument, their attitude warms up even more. What I enjoy most is precisely this shift: from a “joke” to respect for the instrument as a piece of work.

What challenges do you face when balancing sculptural experimentation with full playability?

The main challenge is the choice of materials and, more broadly, the technical path the project will take. Any deviation from a standard shape pulls behind it a whole chain of questions: how will the weight be distributed, and will the balance and playing comfort suffer?

When you build something sculptural, it’s very easy to get carried away with the purely visual side and forget that it is, in principle, a musical instrument. You have to constantly check yourself: where you can take risks and step outside the familiar schemes, and where you need to hold on tightly to proven solutions. So every project is a combination of image and instrumentality. Sometimes the idea has to be “calmed down” a little; sometimes, on the contrary, you have to look for non-standard structural solutions to preserve the intended look without sacrificing playability.

And lastly, what new projects or directions are you interested in exploring in the near future?

I deliberately don’t limit myself to one technique or a pre-set set of themes. I don’t know what will inspire me tomorrow, and for me, that’s the point of being an artist: spontaneity. An idea can appear out of nowhere, from the most ordinary object that suddenly catches your eye. Today it might be noodles and doughnuts; tomorrow it could be something completely different.

I want to keep that freedom, to react to the world around me and turn my observations into objects that you can both hang on the wall and hold in your hands as instruments. Technically, I don’t rule out continuing the line of conceptual guitars or moving into some adjacent formats, but the principle stays the same: first the idea and the meaning, then the realisation. I try not to build overly rigid plans and to let the next project appear naturally.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.