10 Questions with Kim Matthews

Kim Matthews makes nonobjective sculptures and drawings in various media. The frequent use of modular construction arose from practical concerns—the need to be productive with limited studio time—and spiritual ones, as repetition is evocative of the mantra meditation that structures her daily life. The recipient of a 2010–2011 Jerome Fiber Artist Project Grant, Ms. Matthews exhibits in nonprofit and commercial venues throughout the U.S. In 2017, she participated in her first international exhibition in Ukraine. Her work is featured in Lark Books’ 500 Paper Objects and Artistry in Fiber, Volume II: Sculpture, published by Schiffer. Ms. Matthews was born in Anchorage, Alaska, grew up and attended college in Maine, and has been living in Minneapolis, Minnesota, since 1984.

Kim Matthews - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Kim Matthews is interested in the ineffable qualities of “objectness”—what is sometimes called aura—as well as materiality and process as vehicles for spiritual engagement and healing. She views making art as a complementary discipline of devotion to her long-term meditation practice and invites the viewer into the work and toward introspection through her highly tactile surfaces.

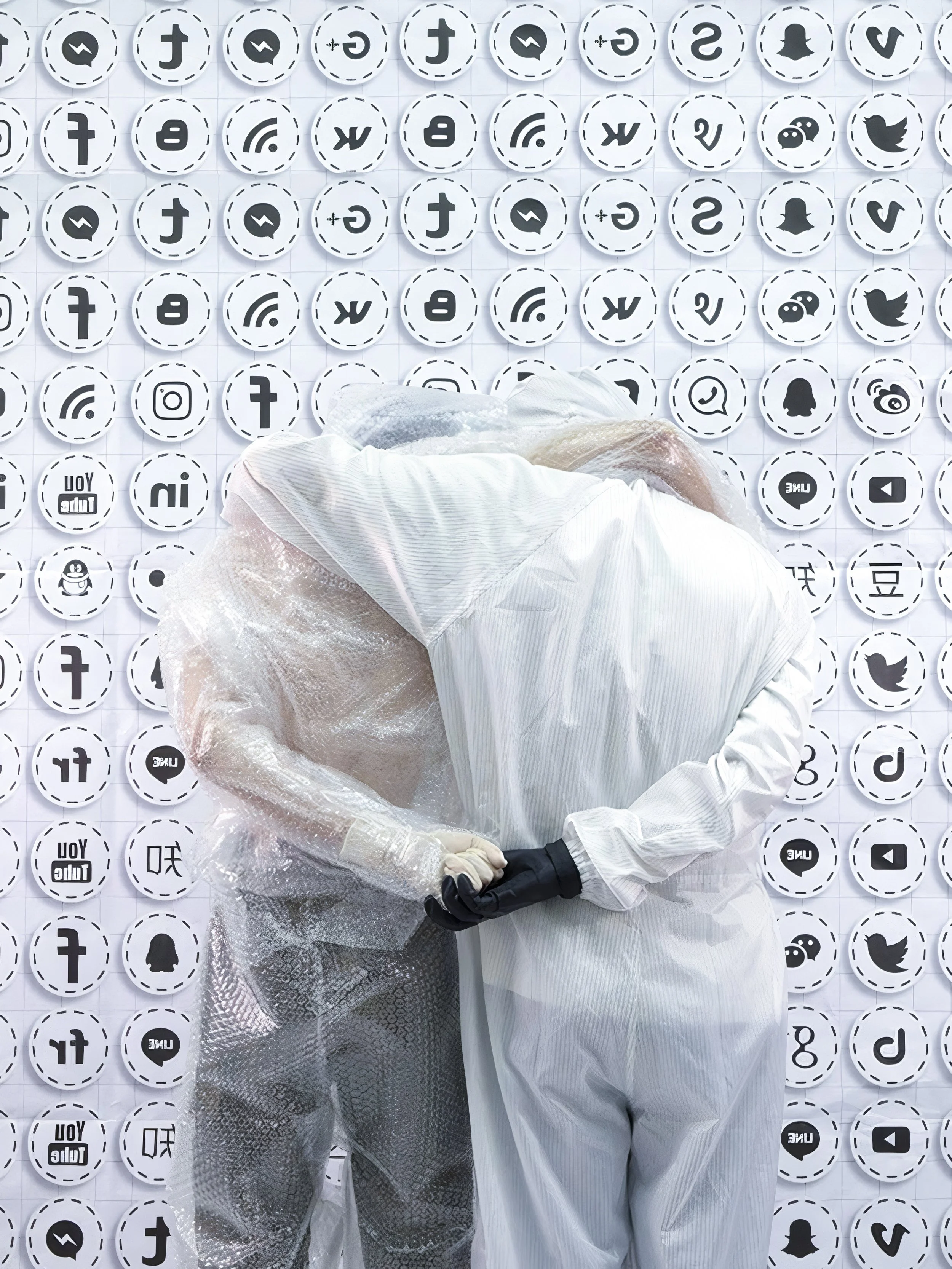

The sculptures in the ongoing Objects of Affection series were prompted by an urge to reclaim comforting childhood memories and honor the artists and designers whose work informed her early visual lexicon—Peter Max, Milton Glaser, Seymour Chwast—and the brightly colored design objects she yearned for: inflatable furniture, the Panasonic Toot a Loop radio, Op-Art prints, and so on. As a small child growing up in the Vietnam War era, she was exposed to a daily television diet of the horrors of war and violence against those who protested to end it. The civil unrest in the aftermath of the George Floyd murder, the political climate and events leading up to it, and the disorienting effects of the coronavirus pandemic evoked the persistent anxiety of her formative years and stirred deep recollections of the powerful impact of joyful imagery, forms, and messages.

In challenging times, she recalls a quote by the writer Joseph Campbell: “We cannot cure the world of sorrows, but we can choose to live in joy.” While it’s difficult to determine whether our individual efforts to create peace are having any impact, she believes in the interconnectedness of all life and that each action and intention affects the totality. Her work is an offering and an invitation to experience connection and delight.

DO1: Hard (prototype), Acrylic on birch plywood, 22 x 22 x 32 in., 2021 © Kim Matthews

Get your limited edition copy now

INTERVIEW

First of all, introduce yourself to our public. Who are you, and how would you describe yourself as a person and an artist?

Hello, public! There's so much focus on identity these days, I don't really want to get into it. I'm a spiritual being having a physical experience. My project is art as service. I believe we're all connected and that somewhere there are enough people who can experience some kind of pleasure or insight from being exposed to what I make that it's worth it for me to keep going. Mind you, I don't always feel that way, but it's been a good week!

What is your artistic background? And when did you first realize you wanted to be an artist?

There's the question of knowing who one is, and the question of how to navigate that. At some point in the late 1960s, I got my hands on paper and things to make marks with, and that was it. My mom taught me how to read when I was 3, and with the reading, I suppose, came writing and drawing. And paper cuts. It seemed like I was always getting in trouble with her for using her pinking shears or leaving paper scraps around the house. Then when I got to school, I was pretty quickly rewarded for some apparent artistic talent and used my drawing skills to impress my peers and teachers. It didn't take long before I realized I'd found my life's work. But once I got to high school and had to think about how to live an adult life, the joyfulness was over. Artist isn't a stable, "respectable" profession; you must be a teacher or at least a graphic designer or something. My parents were in no position to help me navigate much of anything; I graduated high school just before my 17thbirthday and went off to college to get out of the house and was utterly terrified and unprepared after being an art star all through school. The other kids were at least a year older than I was and seemed serious—disciplined. My roommate, who came from this tiny Russian immigrant community in Maine, showed up with a full-on, grown-up, beautiful portfolio, and she was just in the art ed program—no plans to make it big in New York or any of that. I struggled at the University of Maine for two years, then dropped out and moved to Minneapolis to live with my big brother. I needed structure and support. It took me a while—jobs, counseling, reading, commercial art school, meditation instruction, and practice, then to the University of Minnesota with the intention of giving my education the serious attention and discipline it deserved. I also was working full-time at a demanding job and had just started exhibiting professionally. Then the dot-com bust happened, I lost the job that enabled me to pay my way through school, and I had to drop out again. The consequences of all those decisions are a real mixed bag, let me tell you.

Barker, Concrete, acrylic, styrofoam, 12x12x12 in, 2021 © Kim Matthews

Kite3, Concrete, acrylic, styrofoam, 13x15x4 in, 2022 © Kim Matthews

You work primarily with sculptures, and you address the concept of "objectness." Could you tell us more about this? And how does it influence your work?

More ancient history: When I was little, I was lucky enough to live in a magical 1840 sea captain's house in midcoast Maine. My parents worked for an auctioneer in the summers and collected antiques too, so I suppose that's how I got into old things. I started out collecting old bottles, 1930s World's Fair memorabilia, and other stuff that was interesting—some pottery and advertising items.

Anyway, when we had to move from the aforementioned magical house in 1973 because my folks couldn't afford to heat it, I experienced this intense, lasting bereavement and eventually realized it was because I'd lost a friend and protector in addition to all my school chums and all that. So I've always had that deep feeling of connection to objects and buildings and to particular places—really, by that, I mean the Atlantic Ocean, but I was born on the Pacific and can feel its pull when I go to visit my brother in Washington state too.

Later on, I started getting more involved in various spiritual inquiries, had read about psychometry (the "woo-woo" kind, not as in psychological testing), auras, and then through my meditation practice, got all the way to yantras and other sacred art forms, which are tools. Unlike precise instruments like yantras, though, I try not to overprogram or predetermine what I'm doing but rather let the form with its purpose—whatever it is—emerge as it will.

You have to start with something, so often, a form I want to realize will just show up in my mind's eye, and I'll jot down a couple of notes or sketch, so it's a combination of the planned and the accidental, which is evident in the work and which makes it visually lively. I like the surprise of moving in close on something that looks pretty clear and regular from a distance; depending on whose work I'm looking at, it can be incredibly gratifying, so I am aware of that too. To finally answer this question, I just make what I need at the time—to cheer me up, to make me feel safe or nurtured, to contain and transmit the love I have for another being or beings, or just because I want to see what something does when it exists in three dimensions.

Process and materials are equally important for their generative qualities. One gesture leads to the next, and so on, or a material behaves in a particular way under certain conditions. So the experience of making is also embedded in the work and informs what it ultimately "does."

What are the other themes behind your work? And what does your art aim to say to the viewers?

You never know what a viewer's point of entry will be, so I think one has to try to have something for anyone (not everyone, to steal a phrase from Jerry Saltz). I hope that there's a high enough level of craft and formal quality in my work to engage formalists. There are plenty of references in there—from the 1960s and 70s pop culture, Brancusi, Eva Hesse, Vasarely, Bridget Riley, and Bauhaus. I mean, you read about things and look at work and listen to music, and it nourishes you and becomes part of you, so it's kind of hard to tease it all apart. I would say, though, that over the course of my career, the larger theme that has been there all along is growth. I've always used my work to try to figure out what's going on inside myself or in the world, to measure change, to serve as some kind of map or breadcrumbs along the way since it's hard to understand experience when you're in the middle of it, so you have to be able to look back and see where you've been.

As for what my art aims to "say" to viewers, I'm suspicious of words around art because they're limiting and enabling in a sense—like in a museum, there are the didactics that frame or even determine some people's responses to the work. You know what's important about an object and why you should care about it, and how it got into the museum. But you should spend time with a work of art in person if you can, and let it sink in. Get your own sense of the thing as well as the historical stuff.

Joy Diffuser, Concrete and acrylic on Q-Tips and styrofoam, 22 x 12 x 12 in., 2021 © Kim Matthews

What is your creative process like? Could you walk us through the whole process, from conception to the final realization?

I alluded to this earlier. Sometimes I plan and execute with little or no alteration to the original concept, and sometimes I experiment with forms, then construct them. The part of my brain that would enable me to figure out what a 3D thing looks like in 2D doesn't really work; I took technical drawing in school and got assignments back saying, "Nice inking, but this is wrong," so I tend to go right to the materials. I'm also not very playful. I'm more calculating—I sort of run the numbers in my head: Will it work or not? I do color tests because the color is so context-dependent, but if I'm working out a form, I have it roughed out in my mind before I start trying to build it.

The rest is a closely guarded secret, though I post process shots on Instagram and Facebook.

Your pieces have striking and vibrant colors, how do you choose them, and what do they represent for you?

As a sculptor, the way my work has evolved is funny. For years I worked with natural materials and monochrome blacks, whites, and grays. But after things started getting really politically dire in the US, I found myself looking for comfort and started thinking back to all the art and design I loved when I was a kid. Seeing that one 7UP sign outside an old small-town grocery store still makes my heart leap. When I was in maybe fourth grade, Dynamite magazine showed up too, and that was so great; I lived in a very "children should be seen, not heard" home where there wasn't much understanding of children in general, so getting each issue was so exciting because it validated kids' experiences. I've always had this profound emotional response to 60s and 70s design and illustration—intense feelings of joy and desire. So when I needed something to make me feel like everything was going to be all right, that's where I went. I'm not sure anyone's looking at my sculptures and seeing Milton Glaser, for instance, because I have to be me and not an imitation Milton Glaser, but I hope they see the kind of affection, joy, and optimism that are unmistakable in his works.

Anandis Cube, Concrete, acrylic, bamboo, 12x12x12 in, 2020 © Kim Matthews

Your recent series, Objects of Affection, analyzes "an urge to reclaim comforting childhood memories and honor the artists and designers whose work informed [your] early visual lexicon." How do you incorporate both these influences into one piece?

I think I addressed that above. I'm not sure how analytical I am in my work. I just make it, and sometime later on, it tells me what it's about. With the Objects series, I needed to be with those colors, and I was also thinking a lot about how hard love is. I talk about love and the importance of acting from a place of love all the time, I feel like, but it's so hard to actually take those emotional risks when there's so much at stake—and it gets harder the older you get. So, on the one hand, I was putting all the love I could gather into those objects and hoping it would reach people, knowing that I was operating from a relatively safe distance, and on the other, I knew that my work as a human being has to be to open up again—to love deeply and fearlessly in every available way, so I'm trying to get that out thoughtfully in deed as well as word. It is taking a very long time.

I also have a series of drawings going on that have little or nothing in common visually with the sculpture—they're neutral, all 5 x 7 inches on buff laid paper, and mostly geometric. But I started making those as devotional objects after a long-term on-again/off-again relationship I was in finally imploded, and I had to walk away. I needed some kind of heart medicine. I had to draw my way out of the pain, so it was this reflexive process of clarifying what I was feeling and then using those artifacts as tools to heal myself. What's been amazing about that series is the response I get from people. They do something for them, too; I couldn't be happier about that. I'm so grateful.

Let's talk about promotion. You have exhibited extensively. Do you think the shift to digital exhibitions and platforms has helped you promote your work? Or do you still prefer in-person exhibitions?

Well, I don't think it's an either/or proposition. I think on a practical level, one has to do everything possible to get the work into the world. But with the internet and social media and cell phones, everyone's all about being Instagram famous, so it's not like being out there gives you any kind of edge because everyone is out there, and everyone's an "artist" these days. It's a cacophony—too much of everything. It's impossible to sort through it all, and as a result, looking is reduced to a fraction of a second, so there's very little actual seeing going on.

Also, let's remember that a digital exhibition is not an exhibition of one's work unless maybe they're a digital artist; it's an exhibition of two-dimensional representations of one's work, which is a particularly bleached-out experience for people who work in 3D. And digital images have to be a little overdone to compensate—a little too hot, a little too soft, a little too textured, a little too dramatic. If it weren't for the pandemic, I probably wouldn't ever have done so much digital promotion, but I'm grateful for whatever good the work does, however it gets to people. Because my work is so tactile and deals with the intimacy of tiny details, I think it's really important for people who are interested in experiencing it in real life.

Hello World, Concrete, acrylic, styrofoam, 6x10x10 in, 2021 © Kim Matthews

What are you working on right now? Anything exciting you would like to tell our readers?

I'm working on an offshoot of the Objects of Affection series, a group of small wall-mounted works called Kites. I haven't quite gotten my head around what flight means in terms of these works, but it's in there somehow. They're all painted in fluorescent colors, and I'm hoping to do a black light show with them for my upcoming exhibition in Minneapolis, selections from which will also be on Artsy at my dear friend and neighbor Susan Hensel's gallery. Time is running out, so I have to get on it!

And lastly, what is one piece of advice you would give to an emerging artist?

I'm going to cheat and make this a two-part response, if you'll indulge me. 1) Be yourself. If you don't know who that is, commit to finding out and be prepared to live comfortably uncomfortable. 2) Develop a studio routine and stick with it as though your life depends on it. Prioritize your studio practice like a second job, unless you're lucky enough not to need to work outside your studio to pay the bills. Then it's your only job, and you have even less reason to procrastinate.