10 Questions with Haochen He

Al-Tiba9 Art Magazine ISSUE20 | Featured Artist

Haochen He is an architectural designer currently working at an international architectural design firm. He received his Bachelor of Architecture from Cornell University. In his professional career, he is part of design teams working on large-scale sports venues, particularly major NFL stadium projects, where the focus is on creating transformative, community-driven spaces. In addition to this primary practice, he dedicates time to independent explorations that encompass architecture, art, photography, and critical writing. His architectural projects have been recognised through international awards and competitions, while his artistic and photographic works have been exhibited and published in magazines in Europe and North America. Additionally, his writings have been selected for inclusion in magazines in China and Korea. He continues to develop these four areas in parallel, allowing them to inform and enrich one another.

Haochen He - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Haochen He is an architectural and visual designer whose work explores the intersection of ecological systems, human perception, and technological mediation. His creative practice investigates how architecture can serve as both a scientific and poetic response to the uncertainties of climate and society. Through research-driven experimentation, he examines how adaptation, resilience, and collective agency can be expressed spatially. Through experimental works in architecture, he reimagines environmental infrastructure as a generative system that transforms risk into spatial awareness and care. His methodology combines computational reasoning and material intuition, allowing environmental data to evolve into spatial narratives and sensory experience. Working across architecture, visual art, and environmental design, he translates analytical methods into aesthetic inquiries, seeking to reveal how data, atmosphere, and material converge to form new narratives of coexistence.

TerraFlare. Spatial Convergence, Digital Rendering, Variable size, 2023 © Haochen He

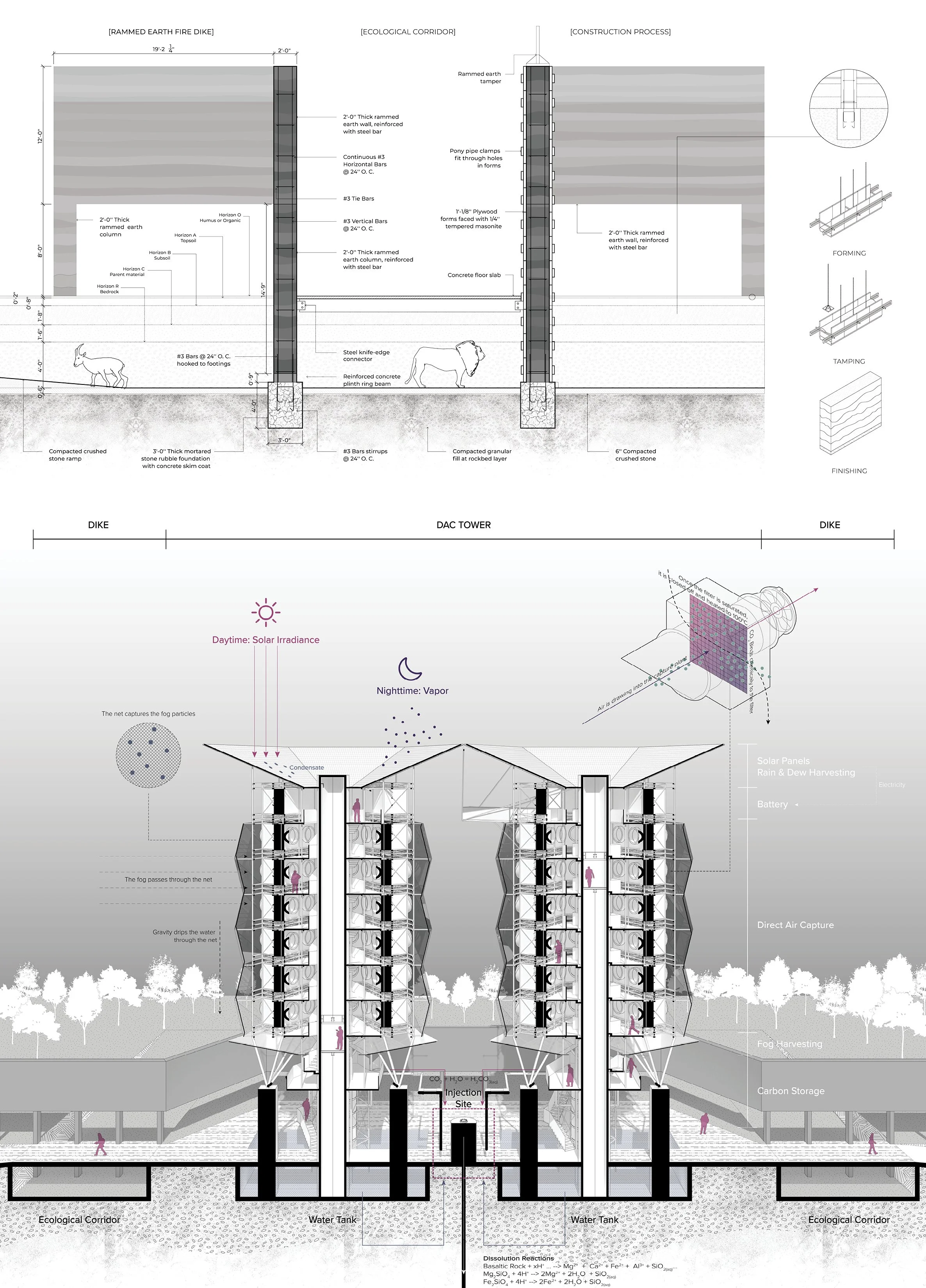

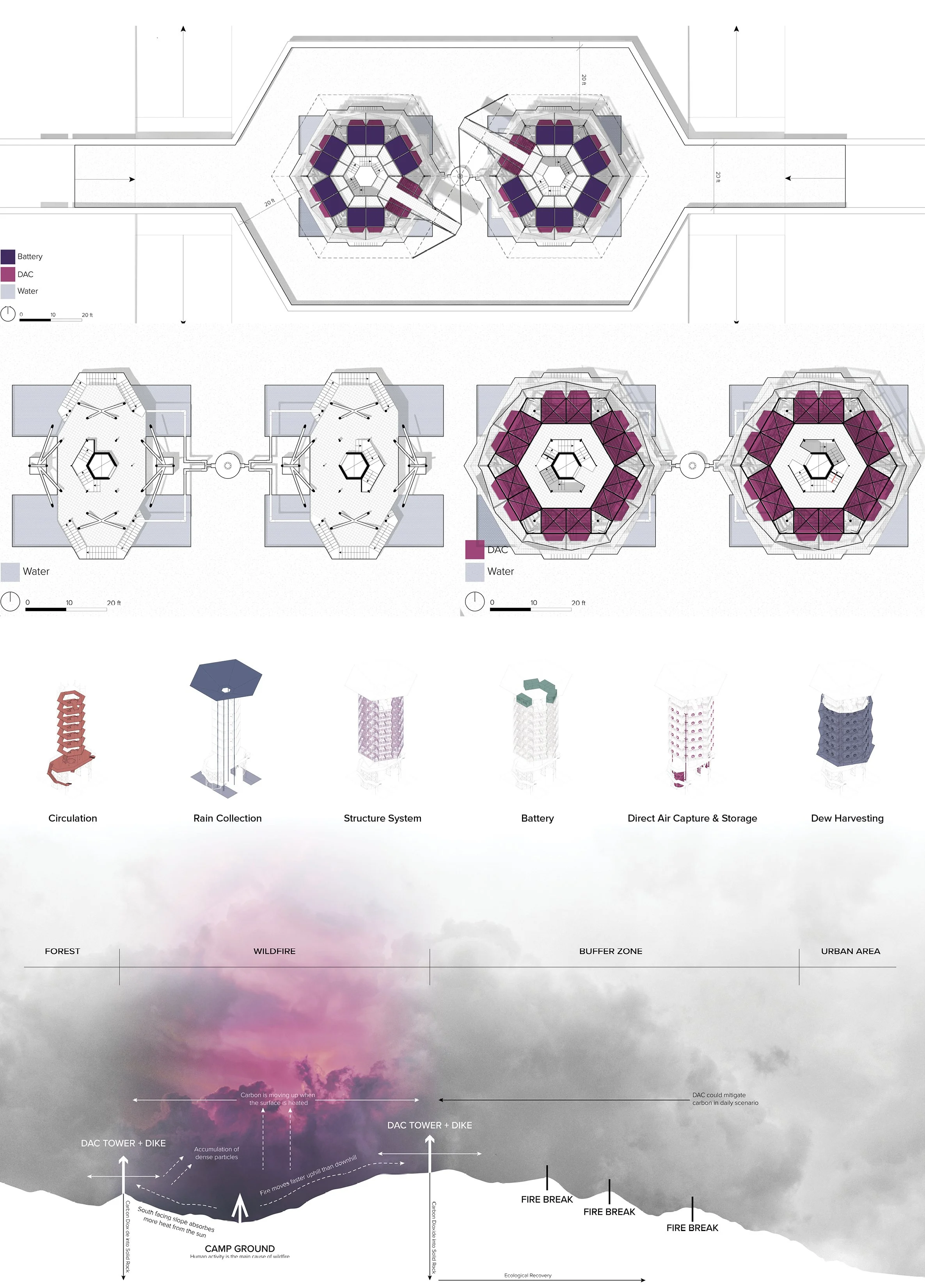

TerraFlare: Uniting Air, Fire, and Community | Project Statement

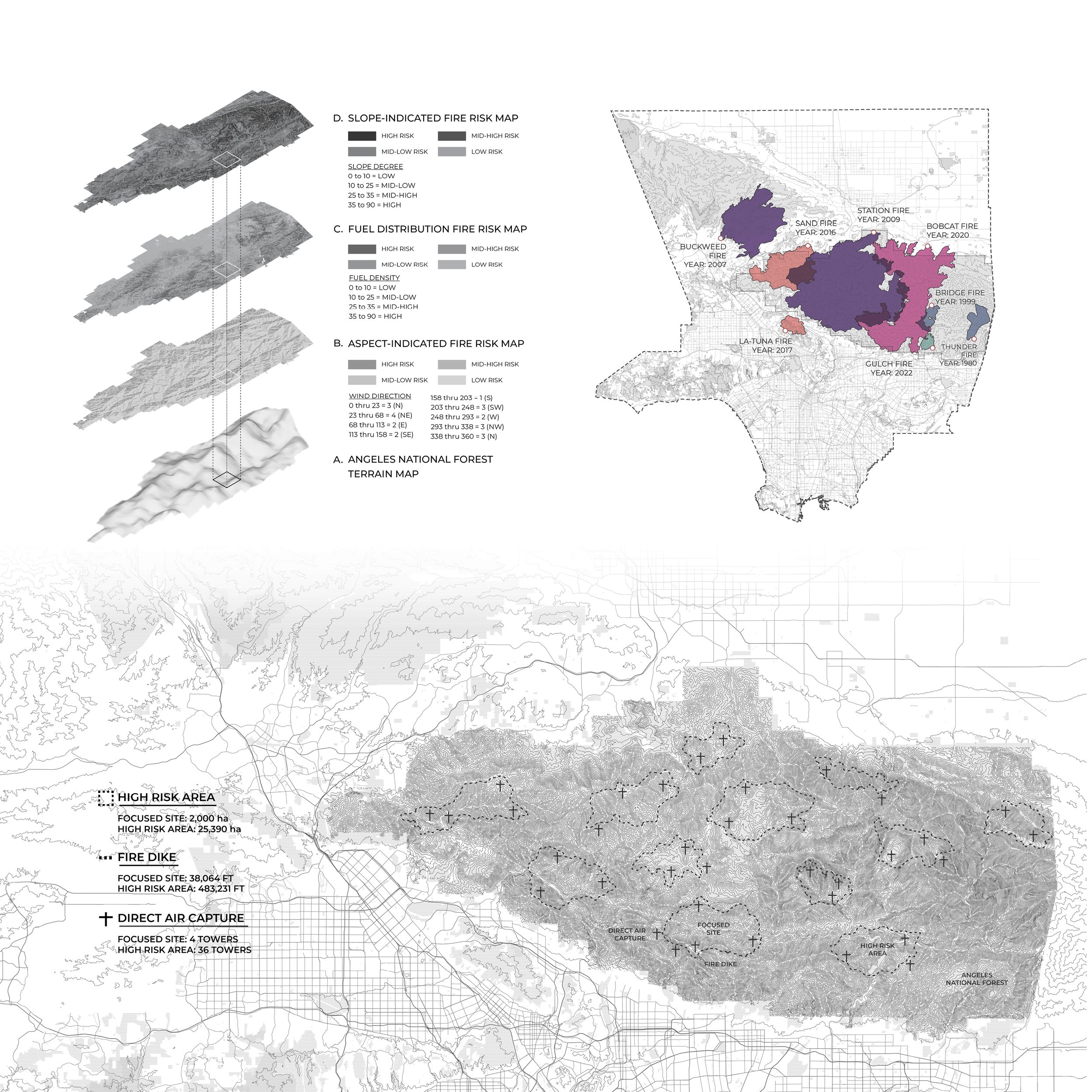

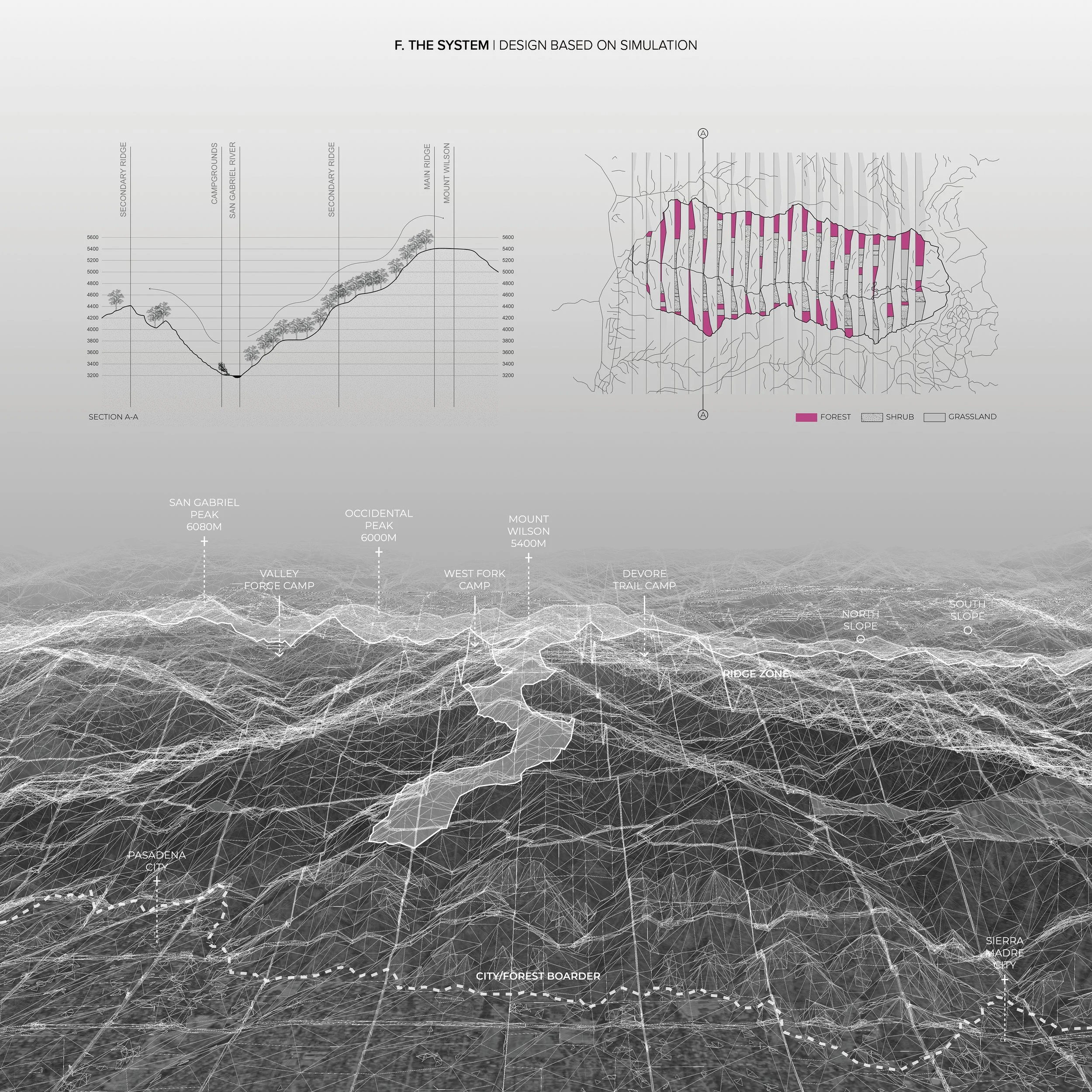

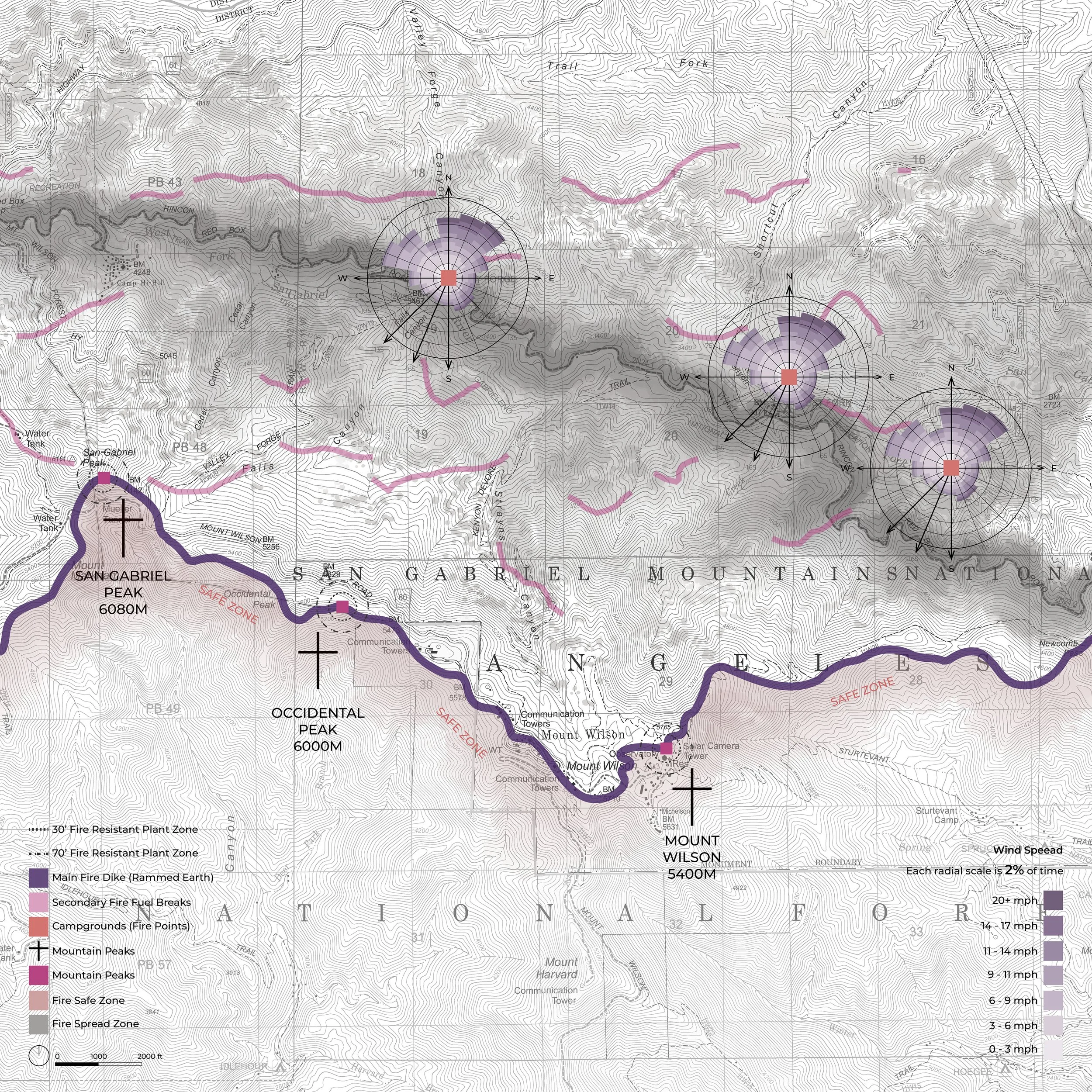

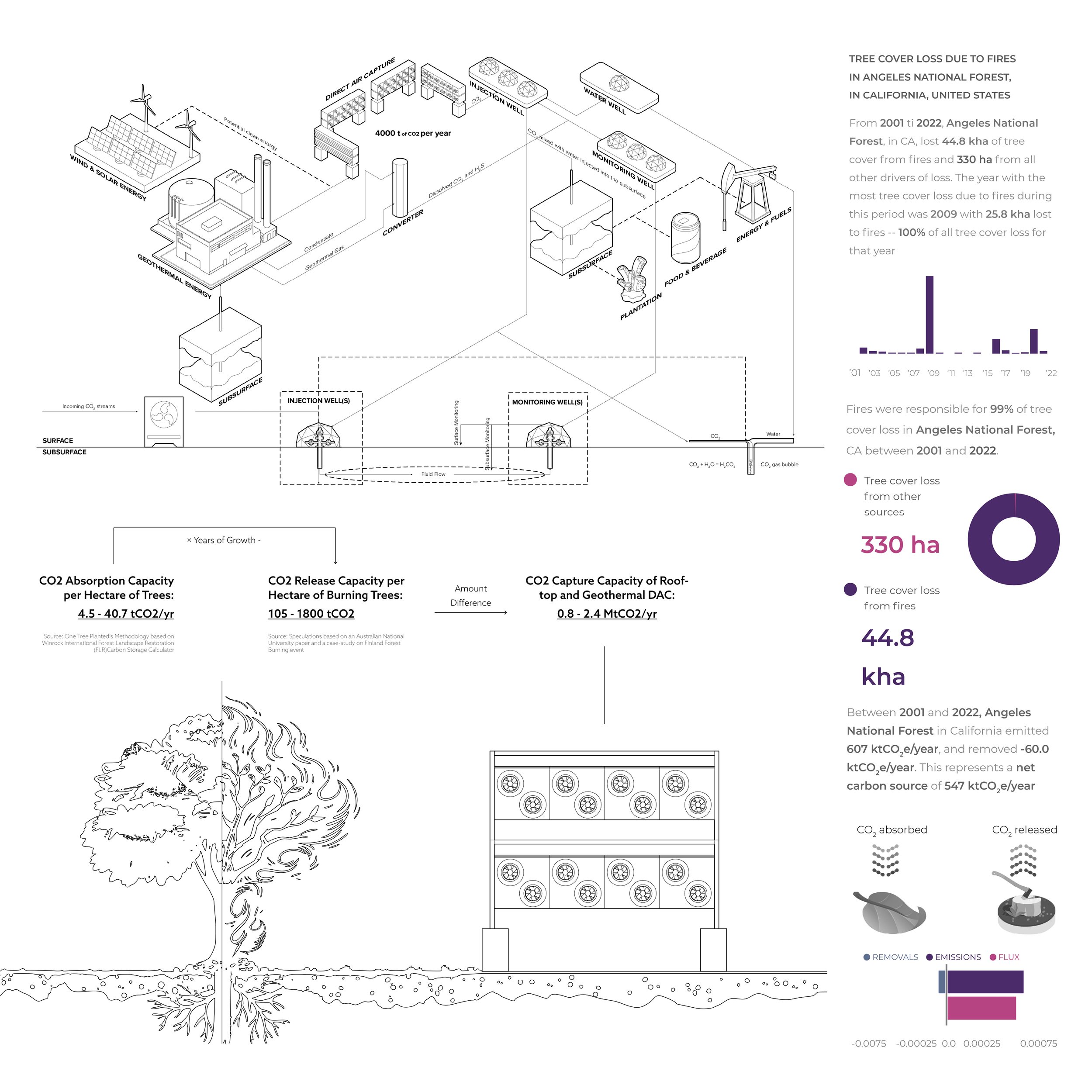

TerraFlare envisions an ecological infrastructure for California’s Angeles National Forest that responds to the intertwined challenges of wildfire and climate change. The project integrates fire breaks, rammed-earth structures, and Direct Air Capture towers to form a continuous system that mitigates risk while restoring ecological balance. The towers function as multifunctional climate infrastructures that capture carbon, harvest water, and generate renewable energy, creating a self-sustaining cycle of resilience. Public access points, such as watchtowers and learning platforms, invite visitors to engage directly with the environment and to understand how design can shape coexistence with natural processes. By merging technology, landscape, and community participation, the project reimagines infrastructure as a living system that transforms vulnerability into regeneration and sets a precedent for climate-responsive design in fire-prone regions.

Location: Los Angeles, 2023

Design Team: Haochen He, Haoyang Li

TerraFlare. Fire and Renewal, Digital Rendering, Variable size, 2023 © Haochen He

AL-TIBA9 ART MAGAZINE ISSUE20

Get your limited edition copy now

INTERVIEW

To begin, could you introduce yourself by telling us about your journey into architecture? What first sparked your interest in design, and how have your experiences and influences shaped the evolution of your architectural practice over time?

I am an architectural designer at an international firm specializing in large-scale sports and venue projects. My academic background from Cornell University is in architecture, and my creative work extends to fine art, photography, and writing. These four areas form the core of my practice and allow me to explore the relationship between space, culture, and visual expression in different ways.

My interest in architecture began long before I could name it. I grew up in a family where everyone was an architect, and design was simply part of the air I breathed. Some of my earliest memories are of sitting quietly at the edge of a table, watching lines taking shape on a piece of paper. I remember the sound of a pencil on drafting film, the way a drawing slowly revealed a space that did not yet exist, and how a slight adjustment could change the entire composition. Those moments taught me to notice proportion, calm focus, and the quiet discipline behind design. They did not decide my path for me, but they showed me what it means to think through space with care, and they influenced how I later developed my interest in architecture.

As I grew older, my practice expanded naturally. Photography sharpened my attention to light, atmosphere, and framing. Art allowed me to explore emotion and abstraction beyond the constraints of a building. Writing became a way to examine the cultural and social questions that shape our environments and to express ideas that cannot be captured through drawings alone. These experiences work together and continually reshape my understanding of architecture. They help me approach design not only as a profession but also as a broader creative language shaped by observation, curiosity, and reflection.

TerraFlare. Carbon Response Scenarios, Digital Drawing, Variable size, 2023 © Haochen He

You work at the intersection of architecture, art, photography, and critical writing. When did you first realize that architecture could extend beyond building design and become a multidisciplinary language?

I first sensed that architecture could extend beyond building design when I began photographing spaces in a traditional architectural way, focusing on straight lines and controlled perspectives. Even within that discipline, I soon noticed that light and atmosphere could transform a simple wall or landscape into something that felt more architectural than a physical structure. As I continued photographing, the camera revealed layers of emotion, time, and spatial experience that drawings and models could not fully convey. It was my first realization that architecture could move through other media and be understood as a broader visual and artistic language shaped by perception rather than by form alone.

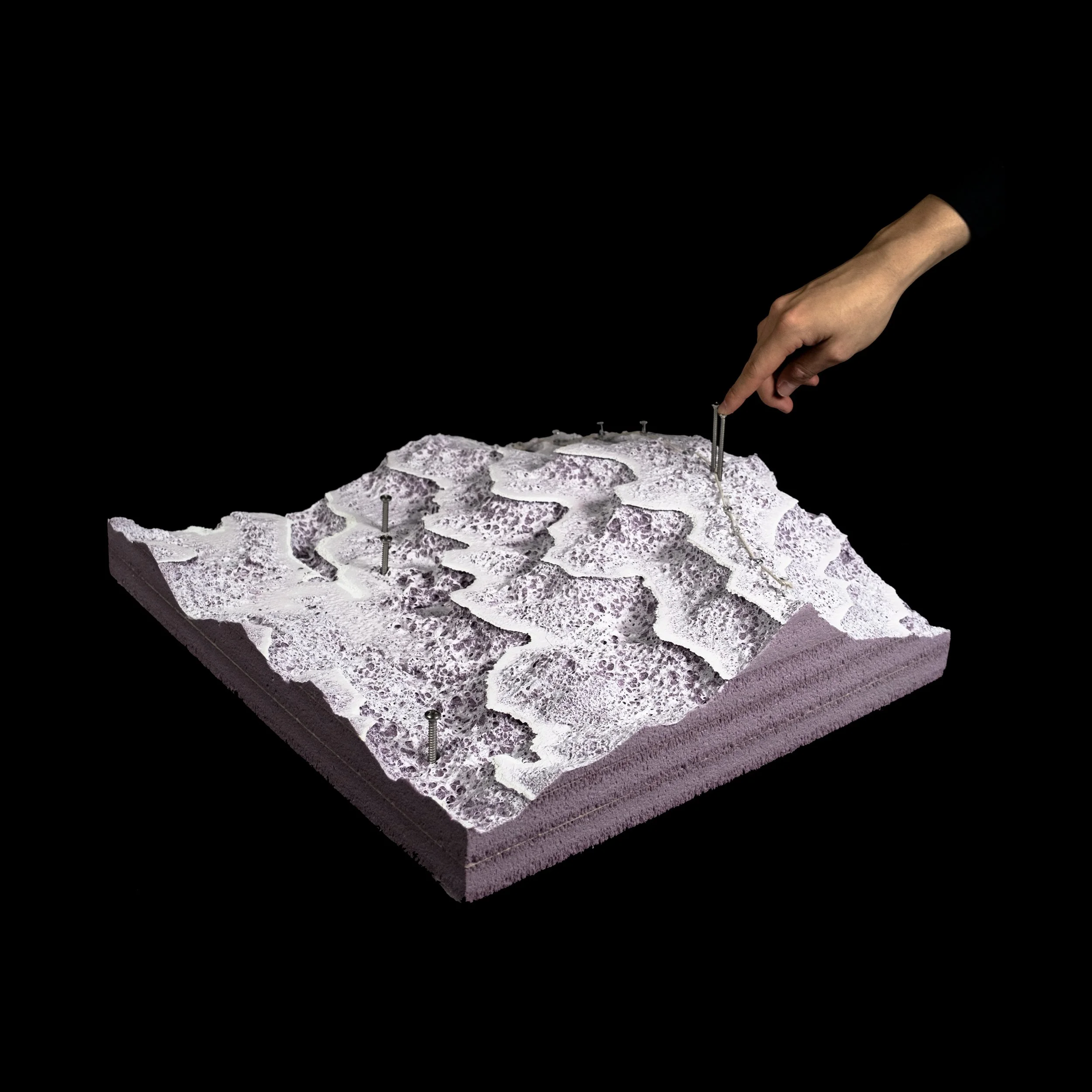

This curiosity deepened as I read more architectural history and philosophical writings. Some of the texts that influenced me led me to think about architecture not only as an object but also as a cultural and even cosmic condition. For example, I explored how natural landscapes can carry architectural qualities through ideas of emptiness and perception, how industrial systems shape urban spaces, and so on. These questions served as starting points for my critical writing, in which I examine themes such as the agency of natural environments, the cultural symbolism of architectural form, and the tension between human intention and larger systems. At the same time, working with physical models allowed me to view architecture from a more tactile, artistic perspective. Some models felt more like installations or sculptural objects than architectural studies, and this made me aware that early design exploration often behaves like an art practice driven by intuition and sensory response.

How did your education at Cornell shape your understanding of design? Were there particular ideas or principles that have stayed with you since?

Cornell shaped my understanding of design through a series of moments rather than a single idea. Some projects focused on construction logic and the practical process of bringing an idea into built form. Others were developed through intensive research and data-driven investigation to explore larger environmental, social, or cultural questions. This variety created a learning environment that encouraged academic freedom, and every designer gradually developed an individual approach.

Over time, I realized that my approach to a project always began with research. I developed a workflow that starts with cataloging existing conditions and reconstructing an existing scenario to understand how a place or system currently operates. It includes collecting information through observation, documentation, and data-based investigation. After building a clear picture of the present situation, I move into creating designed scenarios that test different possibilities and reveal new relationships. Every project requires a different level of analysis, and the approach shifts accordingly. This structure of catalog, existing scenario, data-driven understanding, and designed scenario has become an essential principle for how I begin a piece of design or artistic work.

TerraFlare: Constructive Section, Digital Drawing, Variable Size, 2023 © Haochen He

TerraFlare: System Stratification, Digital Drawing, Variable size, 2023 © Haochen He

Your architectural practice engages with ecological systems and technological mediation. When designing, what is your primary goal? And what do you hope a space or structure ultimately does for its environment and its users?

When I design, I begin by trying to understand how an environment already works. Ecological systems have their own rhythms, pressures, and patterns of movement, and my first goal is to carefully read these conditions. I want a project to respond to what is already happening rather than overwrite it, so the initial study of landscape forces and environmental behavior becomes the foundation for every decision that follows.

Technology enters my process to translate these observations into performance. I am interested in how a structure can work with natural systems rather than against them, whether through atmospheric processes, water cycles, or material behavior. Technology becomes meaningful when it supports these relationships and extends what the environment is already doing.

What I hope a space achieves is a sense of reciprocity. A structure should strengthen the ecological processes it touches and, at the same time, offer people a clearer understanding of the place they are in. If a project can protect, restore, or reveal something about its surroundings while creating a grounded experience for its users, then it has fulfilled its role.

You design large-scale, community-driven sports venues in your professional career. What do you think is the social responsibility of stadium architecture, especially when these spaces become cultural icons?

The social responsibility of stadium architecture begins with its role as a place that brings people together. A stadium is never only a venue for a game. It is a civic landscape where identity, memory, and emotion converge. Within sports culture, the stadium functions like a contemporary town square. Families return season after season, entire cities gather around a shared team identity, and the architecture becomes a physical expression of collective pride.

I also believe a stadium must live beyond the event. Large-scale venues should serve their communities year-round, offering spaces for public gatherings, concerts, education, and cultural activities. In this sense, a stadium becomes part of the city's everyday fabric rather than a piece of remote infrastructure. When architecture supports these multiple forms of engagement, it begins to create new patterns of social life. It helps the venue evolve into a cultural icon that is grounded in real community use.

Another responsibility lies in shaping human experience through architecture. Sightlines, circulation, acoustics, and comfort contribute to the energy of game day, but they also ensure that everyone feels included in the collective moment. Good stadium design creates a feeling of connection among tens of thousands of people, turning individual spectators into a unified crowd. For me, this ability to create shared emotional experience is one of the most powerful social roles of stadium architecture.

TerraFlare: Topographic Prototype, Handcrafted Foam Model, 50×50×12 cm, 2023 © Haochen He

Together with your large-scale stadium projects, you also pursue independent research in environmental and visual design. How do you balance these parallel practices, and in what ways do they feed into each other?

I do not need to force a balance between these practices because they naturally support one another. Working on large-scale stadium projects and pursuing environmental and visual research feels closely connected. In stadium design, the work extends far beyond the interior spaces of a premium club. The site master plan, environmental analysis, circulation patterns, and large-scale rendering exercises all require a deep understanding of how people move through space and how a landscape shapes experience. Even tasks such as crafting wayfinding systems or designing the graphic language for a venue draw directly from visual design and environmental reading. These responsibilities constantly expose me to questions that overlap with my independent interests, and they sharpen my awareness of how architecture communicates across many scales.

The exchange moves in the opposite direction as well. The environmental research I do outside of work helps me interpret context more precisely when I approach a stadium site. Visual design and photography shape the way I read light, form, and proportion during early concept studies. And when we explore massing or spatial character in the office, there are moments when model making and form finding rely more on intuition and artistic sensitivity than strict logic. Those moments teach me as much as the analytical work does and often influence how I approach my independent projects later.

Many disciplines inform your practice, from data analysis to photography and environmental design. Who or what are some of the thinkers, designers, schools or artists who have most influenced your multidisciplinary approach?

Alvaro Siza has shaped my thinking more than any other architect. His work taught me that clarity often comes from understanding a place before shaping it, and that minor adjustments can carry a surprising emotional weight. I learned from him how a wall can follow the quiet logic of a landscape, how a path can respond to the movement of light, and how a surface can invite reflection rather than demand attention. Whether I am analyzing environmental systems, constructing a model, or composing a photograph, I often return to the idea that architecture begins with careful observation and grows out of the character of the site itself. This way of thinking becomes visible in many of my projects, even when the scale or technology is very different from Siza’s own work.

Digital twin thinking influences me in a more conceptual way. It encourages me to read a place through parallel layers, where physical observations and data patterns inform each other. This dual viewpoint shapes how I build catalogs, reconstruct existing scenarios, and develop designed scenarios that test new directions. It helps me approach environmental and visual design as an interconnected field of systems rather than isolated disciplines.

Lewis Mumford’s Art and Technics has also been important in shaping my multidisciplinary approach. His writing revealed how creative work is always situated within broader technological and cultural forces. His perspective helps me connect architecture, environmental research, and visual composition as different ways of reading the world, each one expanding the depth and reach of the others.

TerraFlare: Scale-up, Digital Drawing, Variable size, 2023 © Haochen He

TerraFlare: Design Based on Simulation, Digital Drawing, Variable size, 2023 © Haochen He

TerraFlare: Site Analysis, Digital Drawing, Variable size, 2023 © Haochen He

Your work seeks to reinterpret environmental infrastructure as generative rather than defensive. How do you challenge the conventional idea that climate resilience is merely protective rather than participatory or imaginative?

I challenge the idea of resilience as a defensive act by treating environmental systems as active forces that can guide design rather than as elements to be resisted. When I study a site, I look at how air, heat, moisture, and terrain already move through the landscape, and I treat these patterns as sources of possibility. Responding to them directly strengthens infrastructure and supports ecological processes while opening new ways for people to experience the environment.

Climate resilience can also be both functional and imaginative. A structure can manage fire, water, or heat while still creating moments of gathering, observation, or learning. When people can interact with the systems that support resilience, the design shifts from protection to participation. It becomes a way to deepen awareness of the landscape rather than defend against it.

In my own work, I often explore how environmental infrastructure can act as a social and spatial catalyst rather than a background system. Instead of concealing ecological mechanisms, I highlight them as part of the spatial experience, letting atmospheric movement, seasonal cycles, and material transformation shape the architecture itself.

Ultimately, you design structures that are meant to be used, visited, and lived in. How do you hope viewers or users experience your work? And what changes would you like to spark with your designs?

I hope people experience my work through heightened perception. I want a visitor to become aware of their own movement, their proximity to the landscape, and the atmosphere around them without needing explicit instruction.

Digital twin also influences the user experience. It encourages me to see a place as having both a physical presence and underlying forces that shape it. A space can reflect airflow, climate pressures, or environmental rhythms in an experiential rather than technical way. If a user senses these invisible patterns through emotional or spatial responses, architecture becomes a way to understand the world more fully.

These ideas often become clearer in my environmental projects. In work like TerraFlare, even though the project engages issues such as fire and climate, the experience is not framed in terms of fear or protection. Instead, the architecture invites people to observe how the environment behaves, how light shifts across terrain, or how natural systems change through time. By experiencing these conditions directly, users develop a deeper relationship with the land. What I want to spark through my designs is a shift in how people read their surroundings.

TerraFlare: Carbon Cycle, Digital Drawing, Variable size, 2023 © Haochen He

Lastly, how do you envision the future evolution of your practice? Are there particular technologies, collaborations, or environmental questions you are eager to explore in future projects?

My practice is moving toward a model in which digital simulation, environmental research, and experimental visual work are part of a single continuous process. I am interested in how contemporary research treats a territory as a network of climate, terrain, movement, and information, and how digital twins and urban simulations can be used not only for control but also for critical reading of systems. These tools enable building parallel versions of a place in a virtual environment and testing how design decisions affect flows, exposure, and performance over time. It is not only a technical upgrade but also a way to think about architecture as something understood through models.

In stadium and sports work, this way of thinking becomes very concrete. Each event can be treated as a scenario, with specific patterns of arrival, circulation, crowd volume, and dispersal that can be simulated, measured, and compared. By building digital models that include synthetic spectators and their possible paths, I can study how people concentrate, how pressure builds in certain zones, how services and spaces respond, and how environmental factors such as heat or wind interact with these movements. Scenario-based simulation helps me test different configurations before anything is built, and it links my interest in digital research directly to the design of venues for sport and gathering.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a curated promotional platform that offers artists the opportunity to articulate their vision and engage with our diverse international readership through insightful, published dialogues. Conducted by Mohamed Benhadj, founder and curator of Al-Tiba9, these interviews spotlight the artists’ creative journeys and introduce their work to the global contemporary art scene.

Through our extensive network of museums, galleries, art professionals, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide, Al-Tiba9 Interviews provides a meaningful stage for artists to expand their reach and strengthen their presence in the international art discourse.