10 Questions with Zijing Zhao

Zijing Zhao (b. 1997, Sichuan, China) holds a BA in Fine Art from Renmin University of China (2018) and an MA in Contemporary Art Practice from the Royal College of Art (2020). She is currently a PhD candidate at Chelsea College of Arts, University of the Arts London (UAL).

Her recent selected exhibitions include the London Short Film Festival (2025); Athens Digital Arts Festival, Athens, Greece (2024); CCA Resident Space, Goldsmiths, London, UK (2023); Tank Shanghai, Shanghai, China (2022); A4 Art Museum, Chengdu, China (2022); Fermat Museum, Chengdu, China (2021); Skelf Gallery, London, UK (2020); and Assembly Point, London, UK (2019).

Zijing currently lives and works in London, UK.

Zijing Zhao - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Zijing Zhao’s interdisciplinary practice spans film, installation, and painting, using simulation as a method to create bodies and worlds. She names the entities she constructs Monstrous Bodies—beings in continuous states of generation, mutation, and transformation. These bodies challenge conventional frameworks of subjectivity, identity, and gender, opening new narratives and ethical possibilities.

Drawing from historical texts, academic archives, archaeological records, and ecological theory, Zhao’s work weaves together disparate materials into hybrid mythologies. Within these shifting worlds, monstrosity becomes a site of resistance, care, and fluid becoming—a way to rethink what it means to exist beyond fixed borders.

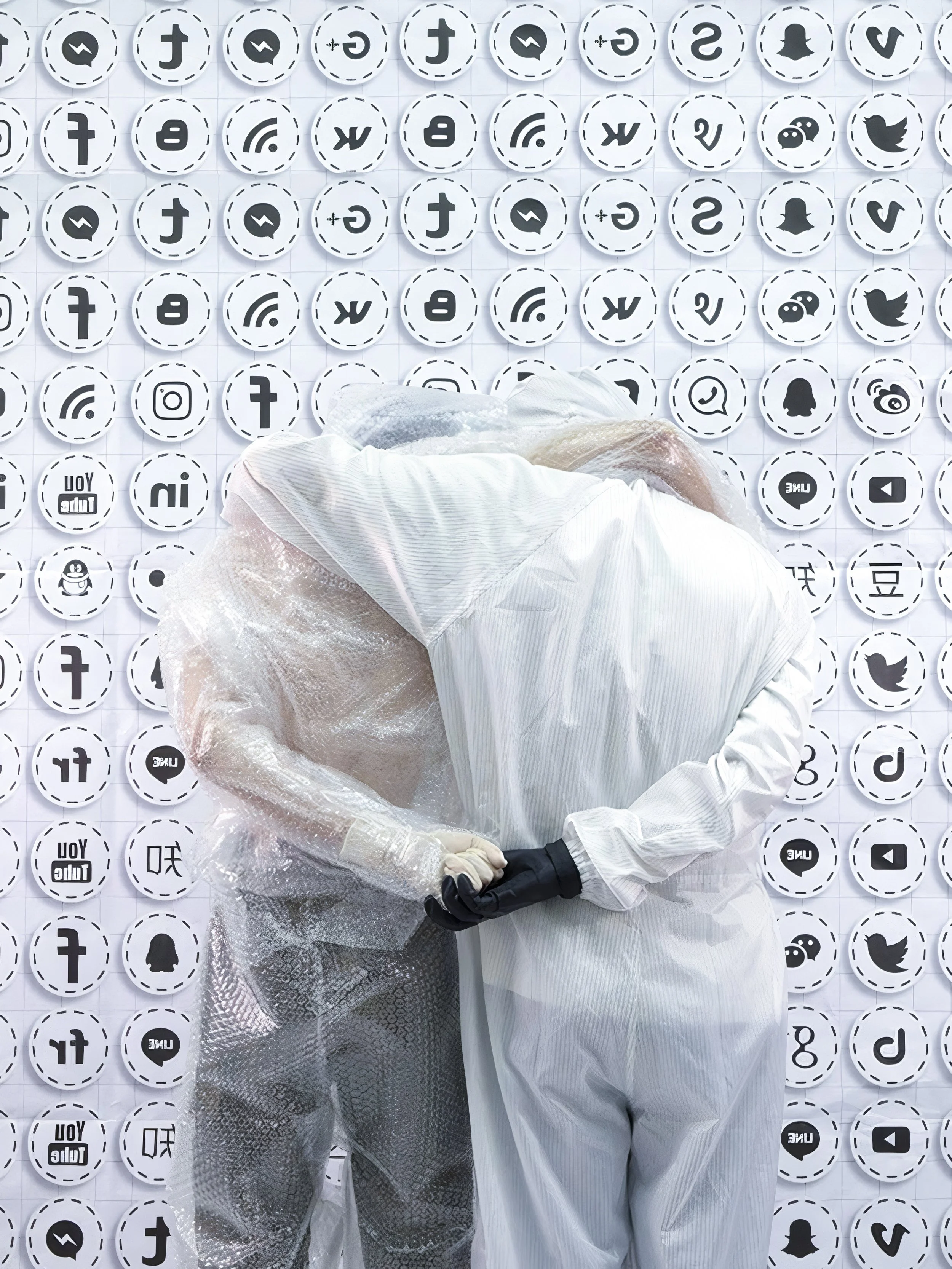

Br00dm0ther’s e-Fable, 2024 © Zijing Zhao

Br00dm0ther’s e-Fable is a short film that combines simulation and performance to deconstruct and reimagine the figure of the female monster in video games. In this work, the Br00dm0ther emerges as a fully digitised, slimy, spider-like creature—capable of devouring, vomiting, screaming, and spawning demons. As she mutates, she becomes a powerful avatar weaving a scientific myth about life, nurture, ecology, and technology.

This project is part of Zijing’s ongoing PhD research at UAL, titled Creating Spaces of Compassion through Monsters: Reimagining the Monstrous-Feminine from Video Games to Art Installation. Through their practice, they explore the concept of the monstrous body—a generative, unruly, and transformative body that resists patriarchal ethical frameworks. Rather than designing fixed characters, they create bodies that invent new worlds and narrative structures.

Drawing inspiration from speculative fiction and posthumanist thought, Br00dm0ther’s e-Fable imagines how monstrous embodiment can destabilise normative identities and open up alternative modes of being. It proposes a future where bodies are fluid, excessive, and radically alive—offering audiences a chance to encounter and coexist with unfamiliar, empathetic forces beyond the human.

INTERVIEW

Can you tell us about your journey from studying in China to pursuing your MA at the Royal College of Art and now a PhD at Chelsea College of Arts? How have these experiences shaped your artistic voice?

My early training in painting in China taught me how to complete a piece of work, whereas British art schools prompted me to begin reflecting on my own practice. During my MA at the Royal College of Art, I studied Moving Image, but I spent most of my time hiding in the basement on the third floor underground, making stop-motion animation. Down there, I was cut off from signal, from light, and from all the classmates holding their Blackmagic cameras. In the darkroom, I shot frame by frame—using rice, rice paper, and wax. This sense of marginality brought a certain frustration, but it also made me realise that my work was never about imitating reality. It was about generating an illusion of life—a form of life that runs parallel to or even exceeds reality. This life illusion can help us imagine alternative possibilities beyond patriarchal capitalism.

At the PhD stage, I began to truly construct a theoretical universe of my own. I use feminist theory, monster theory, and animation theory not just as references but as structures that form the skeletons of monstrous bodies. Through them, I reorganise and generate new worlds.

Growing up in Sichuan and now living in London, how have these different cultural environments influenced your work and perspective?

I've always found myself existing in a state of outsiderness. I was born in Sichuan, but went to school in Beijing, 2,000 kilometres away from home. Later, I moved to London. I float between the scent of plants from my hometown in Sichuan, the heavy snow and sandstorms of Beijing, and the metallic tang of rust on the London Underground, a kind of cultural weightlessness. It has taught me what it means to live in a state of diaspora and instability, how to understand otherness, and how to navigate the so-called margins and centres within a globalised world. This in-between condition forms the foundation of my research into monstrous beings—entities that are neither fully alive nor dead but always in the process of becoming.

Br00dm0ther’s e-Fable, 2024 © Zijing Zhao

Your work spans film, installation, and painting. How do you decide which medium to use for a particular idea or project?

For me, the choice of medium is never predetermined, it emerges from a mutual attraction between myself and the material. I tend to think of materials not as tools but as co-conspirators. More often than not, it's the material that speaks first that initiates the invitation. I've made bodies out of rice and constructed monstrous maternal figures in Blender using digital clay. Each material carries its own temperament and rhythm of life, shaping not only the narrative form but alsothe logic of the world it inhabits. In other words, I'm not selecting a medium. I'm nurturing a character, along with the world it requires in order to exist.

What does a typical day in your studio or research process look like? Do you follow a routine, or is it more intuitive and research-driven?

One thing I absolutely need is a good playlist that can tune me into that focused creative state. Music like that makes me genuinely happy—it lets me slip into the work almost without thinking. After that, I might read a novel, play a game, or just stare into space. My method is really just about listening to irrational impulses. When a character or a body starts to appear repeatedly in my mind, that's the signal. I have to respond to her—even if it means getting burned by materials, being rejected, or ending up crying in the studio after yet another failed attempt.

The concept of Monstrous Bodies is central to your work. What inspired this idea, and how do these figures help you explore questions of identity and transformation?

The monstrous body is one of the central concerns of my practice and PhD research. The initial inspiration came from a monster I encountered in another world: the first time I met the female creature Broodmother in the game Dragon Age, I was forced to kill her with my own hands. She was a bloodied, voiceless being—programmed as an entity that must be destroyed. And as a player, I carried out this patriarchal logic of violence. I felt a profound sense of betrayal. I had betrayed a possible, non-normative figure of femininity and maternity.

That moment stayed with me. It shook me deeply. I began rewriting her narrative. I pulled her out from that filthy dungeon, and placed her into the gallery, into the cinema. I reimagined her as a spider goddess—intelligent, compassionate, and powerful. She was no longer a target to be eliminated, but a storyteller, a dream-weaver, a body reclaiming its own sovereignty. At the threshold between historical fiction and technological fiction, I began to understand the immense generative force contained within the monstrous body itself.

Br00dm0ther’s e-Fable, 2024 © Zijing Zhao

Br00dm0ther’s e-Fable, 2024 © Zijing Zhao

Your practice draws from sources like historical texts, academic archives, and ecological theory. What role does research play in your creative process?

I always treat research as a process of kneading clay, rather than compiling a literature review. I'm drawn to a Borges-like approach—embedding real theoretical material into the strange universes I construct, letting them become part of the imagined background. These theories don't appear directly in the work, but they seep into the bone structures, the logic of the world. I use a method of turning "theory" into "body." It's a bit like mixing everything together, sealing it up, letting it ferment—and eventually, something else grows out of it, a different kind of nutrient. For me, theory must be entangledwith practice. Together, they form the way I conceive, experience, and produce life forms.

Your recent project, Br00dm0ther's e-Fable, presents a powerful reimagining of the monstrous-feminine in digital form. What drew you to explore the figure of the female monster, and how did this inform the character of Br00dm0ther?

I have to admit I was scared by the game at first. The first time I encountered the Broodmother in Dragon Age, I almost dropped my mouse. Her body was raw, swollen, and moaning—covered in blood and flesh. My instinct was to kill her. But at that exact moment, I also felt I had betrayed her.

I wanted to build a body for her that didn't rely on any original prototype—a body without roots. As Agamben writes, a body "without a model, yet always significant." In Blender and Unreal Engine, I kept kneading and stretching an elliptical form, sculpting her in a universe untouched by patriarchal trauma. She is both a creator and the first arrival. She becomes the mother of the universe.

This work blends performance, simulation, and myth-making. How do you see Br00dm0ther's e-Fable contributing to the broader conversation around gender, technology, and embodiment in contemporary art?

I wouldn't call it a "contribution," but I do hope it acts as an intervention. Much of the discourse around gender and technology still operates within binary frameworks. What interests me more is how the process of making life itself might allow us to reimagine another world.

Br00dm0ther is not about replacing an existing archetype. She marks the emergence of a different bodily logic. In the repetitive acts of kneading and shaping her form, I was reminded of a Chinese creation myth—Nüwa (女娲) standing by the river, mixing water and mud, hand-moulding human figures one by one, and giving them life. This is how humankind was born.

Nüwa didn't create life through sexual reproduction or divine language, but through physical labour and material mixture—through the hands, through earth and moisture. For me, this act is a feminist mode of reproduction—a form of life-making that exceeds binary thinking.

Br00dm0ther’s e-Fable, 2024 © Zijing Zhao

Br00dm0ther’s e-Fable, 2024 © Zijing Zhao

Monstrosity in your work is seen not as something negative, but as a space of resistance and care. Can you talk more about this idea and what you hope viewers take away from it?

For me, monstrosity is not a term that points to fear or abjection. What truly unsettles me isn't the Broodmother in the game—with her multiple breasts, crawling limbs, and oozing flesh—but the clean, standardised, obedient player who unthinkingly executes the kill command. Monstrosity is a crucial strategy in my practice—it gestures toward bodies and experiences that cannot be contained within normative systems that remain unstable, cross-border, and indeterminate.

We often imagine monsters as the other, but what concerns me more is how we continually produce monstrosities in everyday life. Who gets marked as monstrous? And who has the power to define what monstrosity is? I understand monsters as a kind of boundary condition, as a subjectivity still in the making, an unfinished structure of intimacy.

Lastly, are there any new directions, themes, or technologies you're excited to explore in your upcoming work? Where do you see yourself and your work in the future?

Right now, I'm experimenting with metal and welding techniques to build a new monstrous body. It carries a harder, more physically resistant presence. This process has required me to learn how to measure, bend, and weld—skills I hadn't previously mastered.

The body doesn't have a name yet. At the moment, she's just a few bent and welded metal bones lying on the studio floor. But I'm already looking forward to finishing her—and to imagining a new world through her.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.