10 Questions with Ollie Hongji Li

Ollie is a 2023 graduate of Parsons School of Design in New York City, where he earned a Master of Fine Arts in Textiles. He received his BA in Printed Textile Design from the University of Southampton (England) in 2019. In 2023, Ollie was honoured with the Creative Promise Award from the Surface Design Association in recognition of his outstanding textile artwork. He was also a finalist for the Dorothy Waxman International Textile Design Prize.

In addition to his accomplished body of fibre art, Ollie is also an exceptionally talented textile designer working in the textile industry. His designs are consistently sold through American retail stores as well as high-end fashion houses.

Ollie’s upcoming exhibition at Gallery Shibumi in NYC is scheduled to open in November 2025. Additionally, in 2025 Ollie was honored to be one of 8 selected artists for the cohort of NY-based artist for 4th Bangdung Residency, hosted by Asian American Artist Alliance and the Contemporary African American Diaspora Museum.

Ollie Hongji Li - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Drawing inspiration from nature and religion, Ollie Hongji Li creates textile sculpture using knotting, knitting, crocheting, spinning, and natural dye. Ollie's art reinterprets the traditional yin-yang dichotomy and offers a new perspective on gender roles, aiming to inspire conversations and challenge assumptions about gender, power, and patriarchy. Ollie's background of growing up in China has deeply influenced their artist ideology, and as a gay man, Ollie brings a unique perspective about gender. In Ollie's latest work, he delves into the concepts of masculinity and femininity through textiles.

Ollie focuses on three-dimensional art forms, employing knitting and knotting techniques while working with hand-spun wool and naturally dyed hemp in his textile creations. As a sexual minority who grew up in China, Ollie challenges gender stereotypes and patriarchal norms. Through his work, he aims to empower those affected by patriarchy and to advocate for gender equality.

Sagassum Fish, Textiles, 18x15x10 in © Ollie Hongji Li

INTERVIEW

Let's start with your artistic journey. How did your early life in China and your academic path in the UK and the US shape your approach to textiles and artmaking?

Thanks for getting started on this one! It gives me an impulsion to look back at my past, even though I'm only 30 years old, which is not old enough (laughing), but I did make lots of progress that I should be proud of as an art human being. Textiles and artmaking are just something thought-out in my 30-year-old chapter of life.

I was born with a passion for creating. My parent was a shoe dealer, and I grew up with tons of shoes and fabrics. I guess immersing in an environment like that did have a profound influence and directed me to where I am right now as a textile artist. I trained academically in drawing and painting from childhood to juvenile life. Until college, I started gettinginterested in fashion design, studying fashion and textile design in England. That experience refined my aesthetic sensibilities, deepened my understanding of colour theory, and strengthened my passion for textiles. Living in England made me realize how much I love textile art; Western society has a developed system supporting textile artists.

The United States has good soil in fibre art. Here, many pioneering fibre artists launched their careers and inspired me. Besides that, I'm a gay man who wants to live in a place that is liberal and offers space for every voice. Eventually, I moved to the United States and settled in New York City. While it can be a crazy city to live in, it did offerme a powerful platform where I can share who I am and what I create. Here, I completed my MFA in Textiles at Parsons School of Design. Alongside my academic journey, I have continued to develop my sculptural practice, drawing on the craftsmanship and traditions of my cultural heritage. Above all, my work centres on storytelling: disrupting stereotypes, confronting patriarchy, and giving voice to both personal and collective narratives through the language of textiles.

Kali, Textiles, 18x15x24 in, 2023 © Ollie Hongji Li

You work across several traditional textile techniques, such as knotting, knitting, crocheting, spinning, and natural dye. What draws you to these methods, and how do they help convey your ideas?

To me, textiles art is different from fibre art, as fibre art addresses more materiality, whereas textiles art requires the artist to show fine craftsmanship through their art. Technically, those techniques are hands-on; it allows me to make art from the very original step—dyeing the yarn, spinning them to how much twisted I want them to be, then hand-knot or hand-knit them into sculpture. Knitting and knotting are two sides of my yin-yang concept of gender stereotype breaking. Also, all of those techniques are completely my own signature, one of a kind. Textiles-making is something very important to my art.

Your work powerfully addresses gender roles and patriarchal structures. How did these themes emerge in your practice, and how have they evolved?

I remember when I studied art, I used to struggle so much to find what I wanted to talk about in art. My professor, Preethi Gopinath, once asked us a question in class, which I still find super useful nowadays. She asked, Why do you create? The question seems SO SIMPLE, doesn't it? But try asking that question to yourself—you'll realize it's not that easy to answer.Why do you create? Why the hell must you make art? What do you care about when you create? Why should people care about your work?

If you are a serious artist, you should know that making art is intense, money-consuming, and time-consuming. You will have many lonely moments when you skip parties and concentrate on your practice. If you don't have the budget for art, then you need to have a day job to pay your bills, or apply for grants that allow you to make art. Given all that, why do you still create?

Those questions guide me to gender and challenge patriarchal structure because I care about those topics—and so does my audience. It's a global issue that impacts billions of people in the world, and it needs to be approached in art. Once I have that commitment, I don't need to worry too much about how things evolve—because when you have that mindset, everything that evolves in your art starts making sense and supports your theory.

Green Tara, Textiles, 19x12x15 in, 2023 © Ollie Hongji Li

Garuda, Textiles, 17x16x20 in © Ollie Hongji Li

Textile art has long been associated with femininity. How do you use this historical context to explore masculinity and challenge gender stereotypes in your work?

I am a rebellion artist. I find using art to break the stereotypes and shift the rules is the coolest thing in the world. One day, when I was knitting a scarf just for fun, a girl said seeing a guy doing this feminine craft is so cool—almost like performance art. It shows a rebellious spirit against something. And that inspires me. I consider, why can't I use this as my manifesto for my art? It has such rich content behind the knitting craft itself. It challenges the way people stereotypically assume guys should do guy things—knitting is not a guy thing, and so I have to do it!!! (More importantly, it so incredibly fits my concept in art: breaking gender stereotypes, gender fluidity, reinterpreting yin-yang.)

Nature and religion are key sources of inspiration in your practice. Can you tell us more about how these elements influence your visual language and conceptual framework?

Nature and religion are both healing. I draw inspiration from those because I want my art to have the same property when people see it. Symmetricity is a key role in my visual language. I obtained this symmetrical rule by observing nature and deities from religion—they are always in a certain symmetrical harmony. Also, colour- and material-wise, I like to use plant-based dyeing methods and natural materials to craft my textiles to build a sense of organicity. Hope that answers your question.

You describe your work as a reinterpretation of the yin-yang dichotomy. How do you express this philosophical idea through material, form, and colour?

To not make this yin-yang theory sound too woo-woo, I like to explain this idea as being all about being confrontational yet conforming. That's how I see this philosophy.

The concept inspires a sense of harmony in my work. While textiles have been associated with femininity—a quality I embrace in my practice—the yin-yang philosophy also encourages me to explore masculinity in my art. This tension and interplay have led me to experiment with ropes (heavy-duty) and knotting techniques, materials commonly linked to masculine labour and identity.

The opposite part of masculinity is femininity, which is also included in my practice: knitting. Same with form, colour, and everything in my practice—it's all about showing harmony through conflict.

Parvati, Textiles, 23x20x75 in, 2023 © Ollie Hongji Li

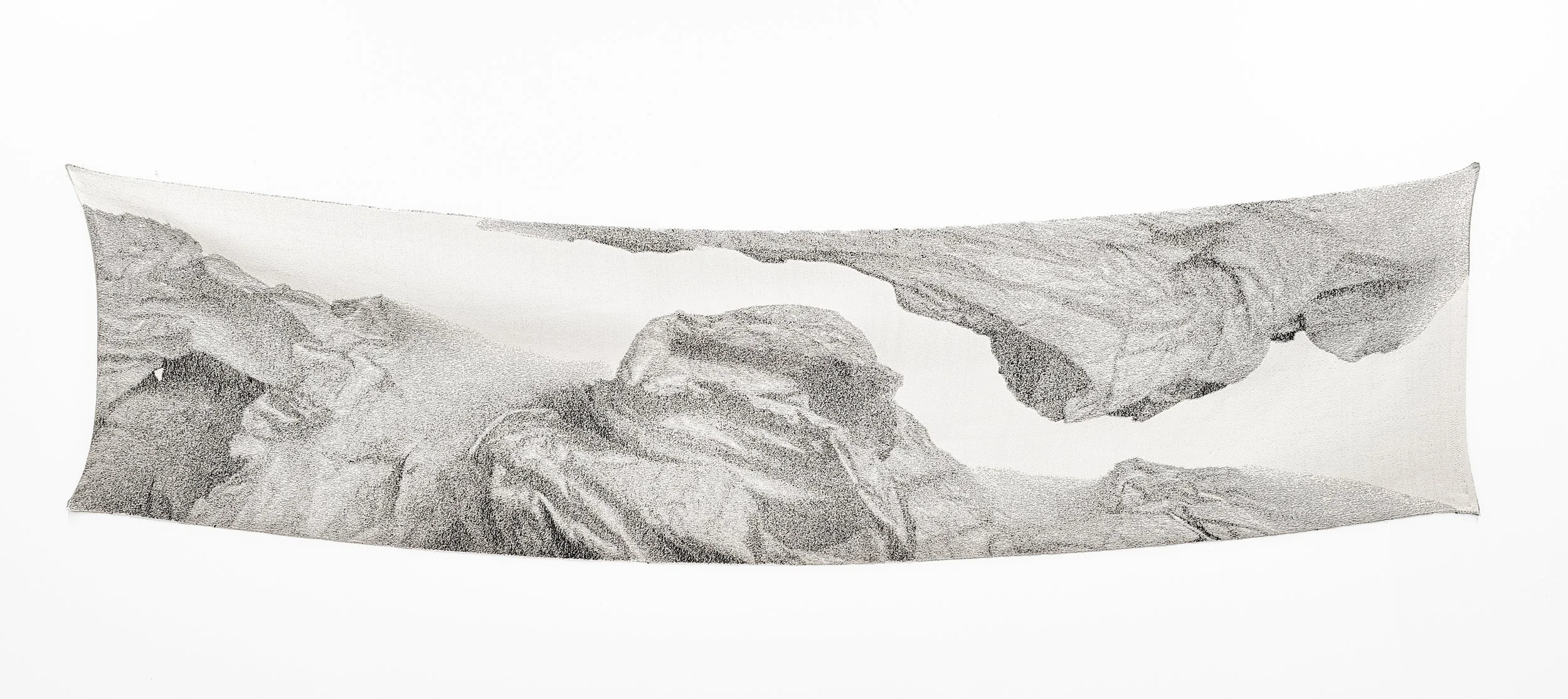

Rage, Textiles, 60x18 in © Ollie Hongji Li

Can you walk us through your creative process, from the initial concept to the final piece? How intuitive or planned is the making phase for you?

I am always fully intuitive but never unplanned. Considering I create all materials by hand—sourcing materials, dyeing my wool and jutes, spinning yarns. I dye colours depending on the emotion I have at that time and on colour experimentation. When I have enough material in my database and feel ready, I sculpt freely—improvised and loose, but strictly following the rule of symmetricity. An artist needs to be brave enough to create something that has never existed before. Having that faith really matters to me.

In addition to your fibre art, you work as a textile designer for fashion and retail. How do you balance your artistic practice and the demands of the commercial industry?

To be honest, I'm not sure how to balance it—I just feel I need to do it, and I want to do it.

My designer job is a Monday-to-Friday on-set job. It's the job that allows me to bring money home, and I create when I'm not working because that's my dream. I save one evening (at least one, sometimes two) each week after my day job to work on my art, and I dedicate one of my weekend days solely to making art. It's intense, it's kind of overwhelming—and guess what? I'm just doing it anyway.

Hyperbolic Organism, Textiles, 14x10x12 in © Ollie Hongji Li

You were recently honoured with the Creative Promise Award and named a finalist for the Dorothy Waxman Prize. What significance do these recognitions hold for you at this stage in your career?

It offers me exposure in the press, stipends to buy materials, and, most importantly, it's an incredible honour and compliment from academics. I think emerging artists in their early careers do need lots of those, and I'm very lucky and honoured to have them, for sure.

Looking ahead to your exhibition at Gallerie Shibumi in November 2025, could you offer a glimpse into what you're currently working on and the themes or ideas you're exploring?

Thank you! I'm very excited about it. My exhibition is titled Future Ancestor—a name that feels deeply connected to my artistic practice. The theme explores the legacy of nations and social memory through my perspective as a Chinese immigrant artist, cultural heritage and diverse identity expressed through my knotting techniques, and the shared lineage and continuity of being human.

The exhibition will feature 15 textile artworks, including six new sculptures that I'm currently working hard to complete. I'd like to extend a special thank you to Gallerie Shibumi and curator Folana Dione for their generous support and trust.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a curated promotional platform that offers artists the opportunity to articulate their vision and engage with our diverse international readership through insightful, published dialogues. Conducted by Mohamed Benhadj, founder and curator of Al-Tiba9, these interviews spotlight the artists’ creative journeys and introduce their work to the global contemporary art scene.

Through our extensive network of museums, galleries, art professionals, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide, Al-Tiba9 Interviews provides a meaningful stage for artists to expand their reach and strengthen their presence in the international art discourse.