10 Questions with KristofLab

Al-Tiba9 Art Magazine ISSUE19 | Featured Artist

KristofLab (b. 1988, Győr) is a Budapest-based interdisciplinary artist. He graduated from the Hungarian University of Fine Arts (Graphic Arts, 2012; Art Education, 2013) and studied at HfBK Dresden via Erasmus. He took part in the Budapest Art Mentor Program (2019–2020) and was a core member of Ziggurat Project (2015–2023), collaborating on site-specific performances across Europe. He participated in residencies in the Netherlands, Sweden, Slovakia, and Austria, and has worked on projects funded by Creative Europe and the Visegrad Fund. His recent exhibitions include Turbina Gallery, ISBN Gallery, and Godot Institute of Contemporary Art. He was awarded the Derkovits Scholarship (2022), shortlisted for the Strabag Art Award (2022), and received the Republican and UniCredit Young Artist Scholarships. His works have been presented at Kunsthalle Budapest, Ludwig Museum, GODOT Institute of Contemporary Art, MODEM, and international venues such as Boston, Seöul, London, Rome, Berlin, Münich, Vienna, Brussels, Warsaw, Krakow. His practice often extends to collaborative, research-based formats.

KristofLab - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

KristofLab’s working method is rooted in artistic research, combined with an experimental approach. He frequently collaborates with creators from various artistic disciplines. In his installations and performances, he integrates multiple art forms, typically designing his works in a site-specific manner. Transitory media, such as video and sound, play a central role in his practice. Through an interdisciplinary approach, KristofLab continuously seeks to expand and challenge his own perspective.

The urban environment serves as a recurring point of departure for his work, offering a symbolic yet sensorially tangible framework through which he explores social concerns, including globalisation and its consequences, environmental issues, war, and social inequalities. In his paintings, installations, and video works, he regularly reflects on the crisis of individual identity, the transformations driven by digitalisation and social media, historical trajectories, and questions surrounding contemporary societal structures.

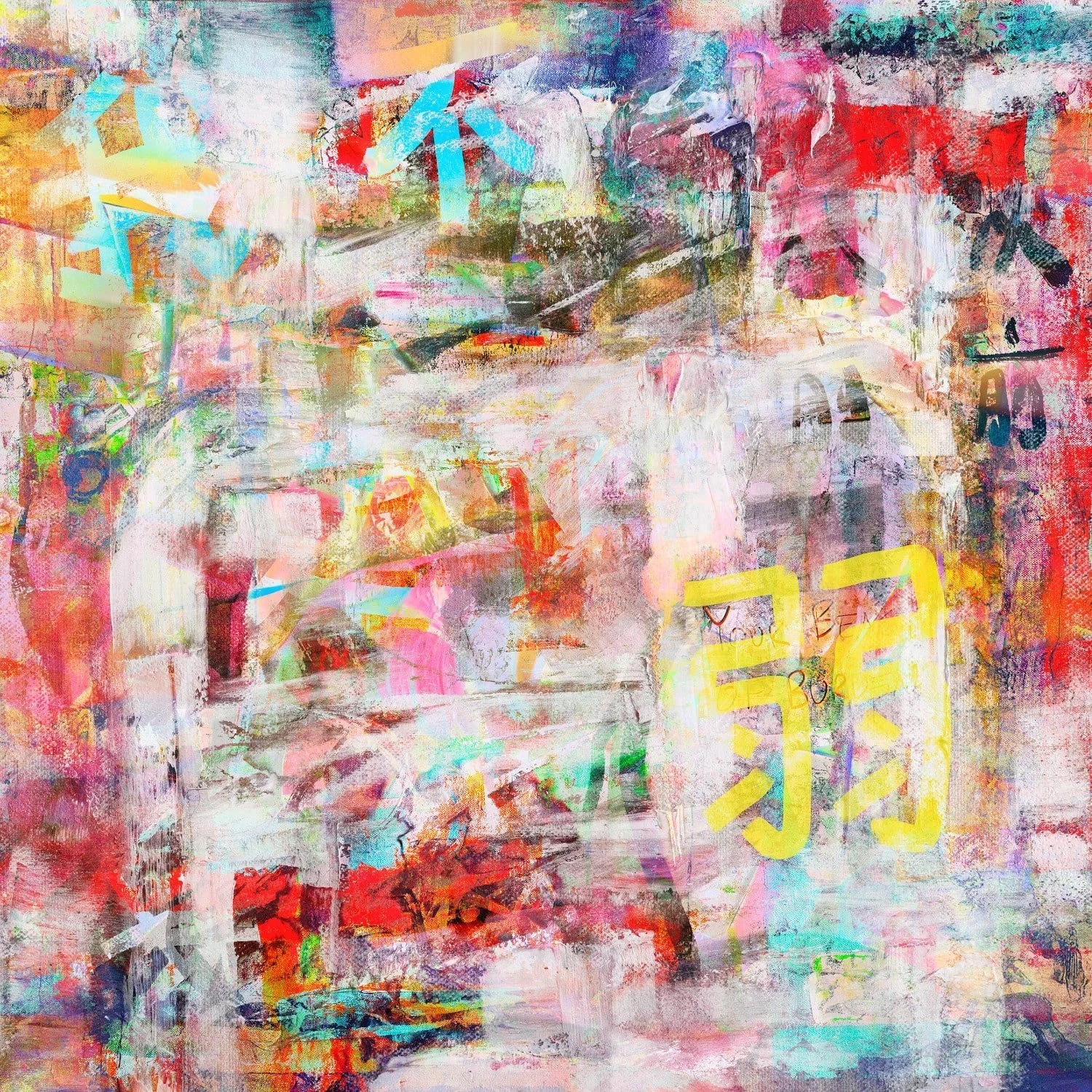

Wrong Data Fehérvár, gicleé on canvas, 50x70 cm, 2022 © KristofLab

AL-TIBA9 ART MAGAZINE ISSUE19

Get your limited edition copy now

INTERVIEW

You began your training in graphic arts and art education, and later evolved into an interdisciplinary practice. How did this transition unfold, and what motivated you to move beyond traditional media?

After graduating from university, I rented a studio in one of Budapest's freshest and most exciting places, MÜSZI. There, I came into contact with the underground cultural scene, bands, and electronic music events, and it was at this time that I began using the name KristofLab. In my visual projections, my own artistic vision gradually emerged, shaped to a great extent by the venue's free spirit and approach to life.

From 2015, I also began working with contemporary dancers and theatre makers, where I could place my new media art experience, gained in the party scene, into new contexts. These collaborations took me to many parts of Europe. My university training in graphic arts gave me the confidence to experiment freely, from manual techniques to digital solutions, providing an excellent foundation for an interdisciplinary approach. My background in art education opened me toward younger generations, helping me remain fresh and experimental.

Human as error I, acrylic canvas, 90x120 cm, 2024 © KristofLab

Collaboration plays a central role in your work. What draws you to collaborative processes, and how do they influence your creative decisions

Early in my career, through residencies and international projects, I took part in initiatives built on collective thinking and knowledge sharing. Collaboration is especially important to me in work that is research-based or that touches on areas where the expertise of others is essential. These experiences helped me understand that creation is never a purely solitary act, even when it is associated with a single name. For me, art has always been a form of discourse, in which the presence of others is not only inspiring but indispensable.

During the pandemic, for example, I created a project built from visual materials sent from different parts of the world. This global collaboration could function even in the midst of physical isolation and opened up new possibilities for interpretation.

This approach also informs my work as a gallery director. For the past two years, I have run an artist-run space in Budapest that functions both as an exhibition venue and an artistic laboratory. Every event and collaborative project feeds back into my own thinking; for me, collaboration always holds new and exciting possibilities.

Research also seems foundational to your methodology. Could you walk us through your process, from initial idea to the outcome?

Each project is organised around some conceptual seed, a word, a social or scientific phenomenon, that triggers a visual search in me. In the initial phase, I create digital sketches and image experiments, which themselves operate reflexively: feeding back into the concept and sharpening the research questions.

I increasingly use ChatGPT during this phase to find sources and map out alternative perspectives, which I then deepen through my own research and note-taking. The technological aspect is important, too: I often need to immerse myself in fields like hydroponics or electronics, which appear in my works not only as tools but also as conceptual elements.

In the experimental stage, I start physically testing materials, forms, and techniques, a process that often takes months. The end result is usually not a single object, but a complex, multi-media body of work that reaches its final form in an exhibition context.

Human as error V, acrylic canvas, 190x150 cm, 2024 © KristofLab

Human as error VII, acrylic canvas, 190x150 cm, 2024 © KristofLab

Your installations and performances often take on a site-specific form. What is your approach to reading and responding to a particular space when creating a new work?

When working on a new installation, I always begin by mapping the space, examining its physical properties, atmosphere, and associated symbolic meanings. It is important to me that the space not serve merely as a backdrop, but engage in an active relationship with my work. My installations are often modular, built from segments, allowing me to reconfigure them differently for each venue.

This flexibility is not only a technical matter but also a conceptual one: each new space offers a different perspective on the same theme. The work thus functions not as a closed entity, but as an open system that can be rearranged and expanded. I often use ephemeral materials, found objects, or pre-existing items placed into new contexts.

Ephemerality, site-specificity, and the singularity of presence are integral to the concept, just as is the fact that such works do not easily fit the expectations of the contemporary art market. I consciously reflect on how the idea of the "artwork" can, or cannot, be interpreted in these cases.

Time-based media like video and sound are key elements in your installations. How do you see these media contributing to the permanence or impact of your work?

The medium of installation excites me because of its site-specificity, its unrepeatable nature, and its capacity for change. Sound and video, as time-based media, naturally fit into this framework: each playback creates a new interpretation.

I often use videos sourced from social media or YouTube that activate collective memory. For example, in my work Transmitter, fragments referencing the events of September 11 are interwoven with emotionally dense images. Such materials are already part of our contemporary visual heritage, but within an installation context, they gain new layers of meaning.

I also create generated videos tied specifically to the given project, such as in Let it flow. For me, sound and moving image are not merely technical tools, but media for expressing questions of time, memory, and presence.

Wrong Data Children play in a park surrounded by destroyed buildings in Borodyanka, Ukraine, in June 2023, acrylic and pencil canvas, 140x195 cm, 2024 © KristofLab

The urban environment recurs in your projects as both symbol and sensory field, as you mention in your statement. Can you tell us more about your relationship with urban spaces and how they shape your reflections on social or political issues?

For me, the city is not only a location, but a social and visual fabric saturated with meaning, an ideal medium for processing individual and collective experiences. Its historical roles, as fortress, knowledge hub, or symbol of power, provide an inherently fascinating structure for artistic reflection.

My personal attachment is also significant: I spent my childhood in the panel block landscapes of the former Soviet bloc, which deeply shaped my relationship to space, identity, and possibility. In my travels, the architectural character of many cities, their orderliness or chaos, has inspired me and provided an inexhaustible source of material. I often see myself as a modern landscape painter, except here nature has been replaced by the built environment. For me, the city is at once a stage, a mirror, and a catalyst.

Much of your practice confronts complex global concerns, from environmental degradation to social inequality. Do you see your work as a form of activism, or does it occupy a different kind of critical space?

For me, art has always been a means of reaching a deeper understanding of how the world works. I am not interested in isolated phenomena, but in the mechanisms behind complex systems, environmental crises, and social inequalities that are linked to political, economic, and historical processes. Through their analysis, I have developed the critical space in which I work: one where the artwork does not provide answers, because answers are often too complex to be fully articulated by a single piece, but instead raises questions, confronts, and creates tension.

My aim is for the viewer to reflect on their own position, how they relate to the world, from what standpoint they perceive, and how visuality shapes their sense of social reality. I often work with digitally manipulated cityscapes, AI, and archival materials, through which the aesthetics of decay and distortion become critical tools.

Although I did not previously consider myself an activist artist, I now find it important that my works convey social sensitivity. A recent exhibition I co-organised with Czech and Hong Kong artists, for example, reinforced my belief that the mode of thinking I represent is legible within a broader, politically relevant space.

Wrong Data Fehérvár, installation view © KristofLab

Wrong Data Fehérvár 71, acrylic on canvas, 140x190 cm, 2022 © KristofLab

In an age defined by digitalisation and media saturation, your work often touches on the fragmentation of identity. How do you explore this theme visually or spatially across different projects?

For me, identity has always appeared as a malleable, constructed, and fragmented reality, especially in the context of digital culture, where self-image is built through mediation. Its visual and spatial mapping is a recurring motif in many of my works.

In the Our Home Place project, I examined how much our sense of self is shaped by our living environment. Using my own photographs, I created non-existent yet familiar cityscapes, presented as installations linked together with chains. The aim was to question whether we shape our environment, or it shapes us.

In Face Switch, I projected other people's faces onto distorted silicone casts of my own, exploring the limits of personal identity. In Ugly Myself, I projected my face onto a sculpture made of garbage, highlighting how the material substrate influences the perception of self.

In Space of Mirror, I projected face videos, collected via social media from acquaintances and strangers, onto movable mirrors. Sliding the mirrors into one another created new, fictional hybrid identities, illustrating that the self is no longer a stable unit but a multilayered, mediated montage.

You've participated in residencies and exhibitions across Europe. How have these international contexts influenced your research interests or aesthetic choices?

International residencies have placed my artistic practice within a broader interpretive framework. These journeys were not only geographical or cultural encounters, but also intellectual and sensory ones: direct engagements with other social realities, visual languages, and theoretical discourses.

The differing institutional systems, public spaces, material practices, and relationships to art in various countries have all contributed to my rethinking of my own position. These experiences made clear how strongly local context shapes what we understand as art, and how important it is to situate this understanding within a more global dialogue.

Particularly influential has been the practice of interdisciplinarity, which, through collaborations with practitioners from other fields, has led to more complex, deliberate uses of media and technological thinking.

My thematic horizons have also expanded. From a Hungarian perspective, for instance, the effects of colonialism are barely visible, while in Western European countries, this historical experience still actively shapes public discourse and artistic thinking. Similarly, the consequences of capitalism or social inequalities manifest differently and with different intensities in London or Warsaw than in Budapest.

These experiences have helped me become not just an observer but a sensitive, reflective participant in these complex systems. In the institutions of a global city, where works looted during colonialism are often on display, an artistic statement is born with a very different sense of responsibility and weight. Such differences deeply influence my perspective and working methods.

N10 WRONG DATA - empty space Sao Paulo, c-print, 50x50 cm, 2020 © KristofLab

Lastly, what directions or questions are currently driving your practice? Are there specific themes or collaborations you're eager to explore in upcoming projects?

I am currently working on my large-scale solo exhibition Fear of the Unknown, opening in February 2026. The project has been developing for a year, focusing on the anxieties and existential questions provoked by scientific and technological progress, from humanity's self-destructive potential (nuclear weapons, climate change) to uncertainties surrounding artificial intelligence, and the socially transformative power of fake news and conspiracy theories on social media.

Formally, the exhibition is complex: through monumental installations, water-based kinetic systems, and a series of paintings, I am creating a hybrid space where scientific knowledge-sharing, speculative fiction, and aesthetic experience are interwoven.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a curated promotional platform that offers artists the opportunity to articulate their vision and engage with our diverse international readership through insightful, published dialogues. Conducted by Mohamed Benhadj, founder and curator of Al-Tiba9, these interviews spotlight the artists’ creative journeys and introduce their work to the global contemporary art scene.

Through our extensive network of museums, galleries, art professionals, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide, Al-Tiba9 Interviews provides a meaningful stage for artists to expand their reach and strengthen their presence in the international art discourse.