10 Questions with Lili Xie

Lili Xie (b.1993, China) engages with the realms of photography, video, performance, and ceramics in her artistic practice. The evolution of her work is an ongoing journey of self-exploration, inquiry, and the deconstruction of her own identity. Through these diverse mediums, she navigates the complex landscape of personal introspection and transformation, using her body as a conduit to express and explore the depths of her inner self.

Her work has been exhibited in England, the US, Italy and China.

Lili Xie - Portrait

Penis Project | Project Description

The Penis Project Series explores themes of gender, power, and cultural conditioning through the lens of satirical advertising, employing a sense of absurd humor. This project was born from Lili Xie's reflections on family gatherings and the conversations around the dinner table—moments where she was often reminded of her family's deeply rooted traditional gender biases.

Growing up in an environment where boys are preferred, Lili Xie encountered subtle and explicit signals that her value would be greater if she had been born male. Her father's longing for a son, her mother's wistful remarks - all of this was grounded in a cultural legacy that worships masculinity, often symbolised by the phallus.

This early exposure to gendered ideals led the artist to question the ways in which identity is constructed and commodified. She began to imagine a fictional world where anyone could purchase penises.

Penis Project © Lili Xie

INTERVIEW

Can you tell us a bit about your background and how you first became interested in art?

I was born in a rural village in southern China, where access to art was extremely limited—there were no museums, galleries, or cinemas, not even stores that sold proper art supplies. As a child, art to me simply meant a paintbrush. My interest in art began with an early fascination with painting.

I studied traditional Chinese painting from a young age. Unlike Western representational art, Chinese painting is not just about depicting forms—it's a practice rooted in rhythm, breath, and restraint. After eight years of study, I came to understand the philosophy of negative space and the subtle wisdom embedded in the brushstrokes. This experience shaped my understanding of aesthetics and gave me a deep appreciation for the spiritual and philosophical underpinnings of Eastern art traditions.

Penis Project © Lili Xie

You work with photography, video, performance, and ceramics. How did you come to explore these different mediums, and what does each one offer you creatively? And how do you decide which one to use for a particular project?

My introduction to diverse media began during my undergraduate studies at the China Academy of Art, where I majored in Intermedia Art. It was there that I first encountered video, installation, and performance experiences that opened up my understanding of what art could be. Later, in graduate school, I expanded my practice further to include photography and ceramics.

Each medium offers a unique creative language, but I don't think of them as separate categories. Their thresholds are broad and often overlap. I'm continually exploring the nature of materials, and I see the medium and its spatial presentation as interdependent. For example, clay—soft, malleable, rooted in the earth—transforms through firing into something hard yet fragile. It's a medium that requires patience and tolerance for unpredictability. Lately, I've been creating ceramic instruments, particularly whistles and masks. When installed on a wall, they function as interactive objects; when held and played, they enter the realm of performance. They also incorporate sound, which adds another sensory layer.

For me, material experimentation and conceptual development happen simultaneously. I don't create based on pre-existing skills. Instead, I pursue ideas that push me to learn new techniques and seek out the medium that best suits the work. I often don't know what form the piece will take. As I explore, I acquire new skills—sewing, cyanotype printing, newspaper design, and video editing. These skills may not always be used immediately, but they stay with me and often reemerge later in unexpected ways.

Penis Project © Lili Xie

Much of your work is about self-exploration and identity. What made you want to use your own experiences as part of your artistic practice? And is there a project or piece that felt especially important to you, either personally or artistically?

I believe that all meaningful art is rooted in the artist's lived experience, whether emotional, intellectual, or bodily. Some artists may choose to express this through abstraction or theory, but for me, personal memory carries as much weight as any academic reference. My work is deeply emotion-driven, often arising from pain, sadness, and longing. Identity is just one of the many threads woven into that emotional terrain.

A turning point in my practice came with the Skin series. This long-term body of work originated from a desire to explore the boundaries of my own body and the layers of identity it carries. I started by creating prosthetics and styling friends with makeup, clothing, and footwear—initially curious about their stories. But as I looked back at the photographs, I realised I wasn't really documenting them—I was documenting myself. The images became mirrors. Through their bodies, I was completing my own narrative, seeing myself in fragments and reflections.

Each photoshoot became a kind of performance. The process was intimate, transformative, and embodied. Over time, the series evolved beyond physical skin and began to touch on social skin—the ways in which gender, power, and cultural expectation wrap around us. One sub-series, Skin–Housewife, was born from my reflections on how patriarchal societies impose fertility anxiety and domestic roles onto women. These expectations aren't always enforced through overt violence—they often come dressed in jewellery and beautiful clothes, yet still confine. I began to see these women not just as subjects, but as surrogates for myself—vulnerable, adorned, constrained.

The Skin series continues to be deeply personal, not because it tells my literal story, but because it visualises the tension between visibility and invisibility, power and softness, longing and performance. In many ways, making art is how I ask the question, "Who am I?"—and how I find new ways to answer it.

Do you ever feel nervous about sharing such personal work with the public? How do you deal with that?

Not really. I actually look forward to hearing how audiences respond to my work. I see the act of sharing as part of the work itself—an extension of the conversation I'm trying to have. Sometimes, I feel like my pieces speak on my behalf, almost like they're confronting the people or systems that have hurt me. They allow me to be both vulnerable and defiant at once.

At other times, the work feels more like wind—gentle, quiet, even invisible, but still capable of moving something inside the viewer. I don't always know how it will land, and that unpredictability excites me. I don't aim to present a finished statement, but rather an open space where my honesty can meet someone else's experience. That exchange, however subtle, is what I value most.

September 15, 2023. Visited the Lincoln Park today, I could not feel Pangpang © Lili Xie

In 2023, Lili Xie encountered a Chumaxian—a shamanic spirit medium from Northeast China—who told her that a white ghost dog had been following her. This spirit was her childhood pet, Pangpang, whom she had nearly forgotten.

Since then, Lili Xie has been quietly reconnecting with Pangpang through tarot readings, whistling, and walks in the park—rituals that blur the lines between memory, spirit, and place. In this project, she is exploring how grief, identity, and belonging live in the spaces between the visible and invisible, between past and present.

Paper is a crucial element in her work. In traditional Chinese culture, paper is burned as an offering to honour and remember those who have passed. In the current piece, the paper grass becomes a fissure—a fragile space where Pangpang and the artist could meet again.

September 15, 2023. Visited the Lincoln Park today, I could not feel Pangpang © Lili Xie

Let's talk about your creative process. Do you usually start with a clear idea when you begin a piece, or does your work evolve as you go along?

My process usually begins with a seed—a small, intuitive idea or emotional impulse. From there, it unfolds gradually through research, brainstorming, and conversations during studio visits. I rarely begin with a fully-formed concept; rather, the work evolves as I keep returning to that initial point of curiosity or feeling.

For example, The Penis Project began with a satirical question: If having a penis means power, then why can't everyone have one? I wanted the piece to feel like a joke—something outrageous enough to make people laugh out loud, and sharp enough to unsettle those who feel offended. From this starting point, the work grew into a whole universe of fake advertising, a catalogue book, fictional newspapers, ceramic whistle masks, and performance. I let the humour and absurdity guide the formal choices, while holding onto the deeper critique underneath.

On the other hand, September 15, 2023. Visited Lincoln Park today. I could not feel Pangpang open a very different emotional channel. It was inspired by an encounter I had with a traditional shaman from northern China, who told me that my first pet, Pangpang, was still by my side in spirit. It took me almost two years to figure out how to share this story. The aesthetics of Chinese painting—particularly its use of negative space—became a guiding reference. I chose not to depict Pangpang directly. Instead, I evoked her presence through photographs of our old walking routes, and through paper objects such as handmade grass.

Much of the piece is made from paper: colored paper, receipts, school labels, tickets, and fragments of my reading notes. In traditional Chinese rituals, paper is often burned as an offering to honour and remember the deceased. In my piece, the paper grass becomes a fissure—a fragile, in-between space where Pangpang and I might meet again.

Each project begins with something personal or speculative, but it never ends where it started. The material, form, and feeling all evolve together in the process.

What are some personal questions or emotions that you often return to in your art?

I often return to questions of absence, longing, and identity. I'm drawn to emotional states that are difficult to articulate—grief that lingers quietly, shame passed down through family lines, the feeling of not being seen or misrecognised. These feelings tend to live in the body and in memory, and my work becomes a space to make them visible.

A recurring question for me is: How do we carry personal and inherited pain? And how can it be transformed—into humour, into ritual, into collective reflection? I am also constantly questioning the ways gender is constructed and internalised, especially within the context of Chinese patriarchy and diaspora.

I think of my work as a site for asking difficult questions without needing immediate answers. Sometimes, just naming a feeling or creating a form for it is enough.

September 15, 2023. Visited the Lincoln Park today, I could not feel Pangpang © Lili Xie

September 15, 2023. Visited the Lincoln Park today, I could not feel Pangpang © Lili Xie

Your work has been exhibited in places such as England, the US, Italy, and China. Have you noticed any differences in how people respond to your work in different countries?

Interestingly, the places where I've exhibited often align with different stages of my artistic development. In China, my works were mostly performance-based; in the UK, I focused on photography; in the US, I've been working more with installation and publication formats.

Each context has shaped not only the form of my work, but also how it's received. In the UK, for example, I felt that viewers tend to let the image speak for itself—they take time to sit with a photograph and draw their own conclusions. In contrast, in the US, the culture of critique is much more prominent. The artist's statement often becomes an essential part of the work, another layer of meaning that is expected to speak as clearly as the piece itself.

One of the most memorable responses I've received came from a recent show in Chicago. A complete stranger sent me a long, heartfelt email after watching my video installation. She shared how deeply the piece affected her, even referencing her own family relationships in response to mine. It was the first time I received such an extensive message from an anonymous viewer, and I was incredibly moved. That kind of emotional connection with an audience is rare and precious to me.

While every location has its own artistic preferences and expectations, what remains constant—and most rewarding—is the possibility of creating moments of genuine resonance across different cultures.

Lastly, what are you currently working on? Is there something new you'd like to explore in the future?

I'm currently developing two ongoing projects, both of which reflect very different aspects of my practice. I plan to continue creating more publications and try puppet shows.

What excites me most about making art is that even with a plan in mind, the creative path rarely unfolds exactly as expected. There's always space for unexpected sparks, shifts, and discoveries.

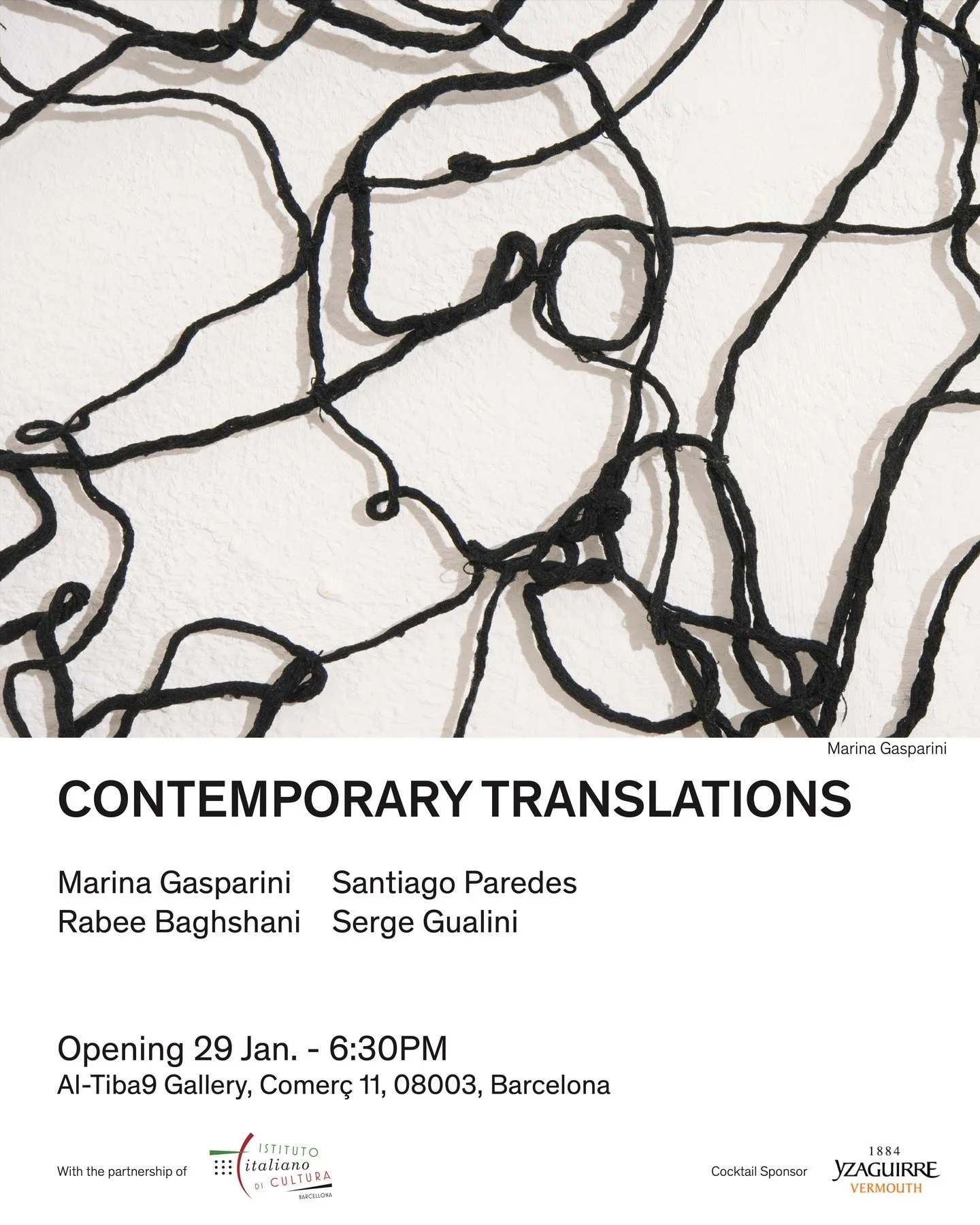

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a curated promotional platform that offers artists the opportunity to articulate their vision and engage with our diverse international readership through insightful, published dialogues. Conducted by Mohamed Benhadj, founder and curator of Al-Tiba9, these interviews spotlight the artists’ creative journeys and introduce their work to the global contemporary art scene.

Through our extensive network of museums, galleries, art professionals, collectors, and art enthusiasts worldwide, Al-Tiba9 Interviews provides a meaningful stage for artists to expand their reach and strengthen their presence in the international art discourse.