10 Questions with Sapphire (Shiyu) Zhang

Sapphire Zhang (Shiyu Zhang) is a Chinese female artist based in the UK. Her interdisciplinary practice merges psychology and art, drawing on an early background in spatial design to explore the relationship between space and human emotion. Working across collage, abstract painting, and installation, her work centres on examining and reconfiguring the structure of emotional experience. She is currently developing approaches that use collage and abstraction to record immediate, in-the-moment feelings, creating a direct dialogue with lived experience.

Her practice also engages with female perspectives, cultural critique, and reflections on traditional culture, including the social stigmas attached to women and to emotional expression. By building connections between personal narratives and collective consciousness, Zhang’s work reflects on identity, emotion, and cultural context, seeking to challenge imposed norms and expand the possibilities of self-representation.

Sapphire (Shiyu) Zhang - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Sapphire Zhang’s practice centres on the transformation of deeply personal and private emotional elements into layered visual narratives. Often incorporating her own image, the nude, or other intimate subjects, her work exposes what is typically hidden, not to shock but to invite resonance. She asks whether viewers, when confronted with the private realities of another, can find traces of their own emotions and experiences reflected back to them.

Working primarily in collage, abstraction, and installation, Zhang assembles fragments of memory, traces of the body, and symbolic imagery into compositions that resist linear storytelling. Each element carries its own significance yet gains new meaning when placed in dialogue with others. Her work thrives on the tension between revelation and concealment, presenting the body not as an object for judgment but as an active subject that asserts its own agency.

Cultural reflection is woven throughout her practice, engaging with traditional frameworks and confronting the stigmas attached to women and to emotional expression. By dismantling and reconfiguring familiar symbols, she challenges inherited assumptions while creating open spaces for interpretation. Viewers are invited to enter her work as they might step into an unfamiliar space, remaining alert, curious, and willing to navigate the shifting conversation between image and memory, personal narrative and collective understanding.

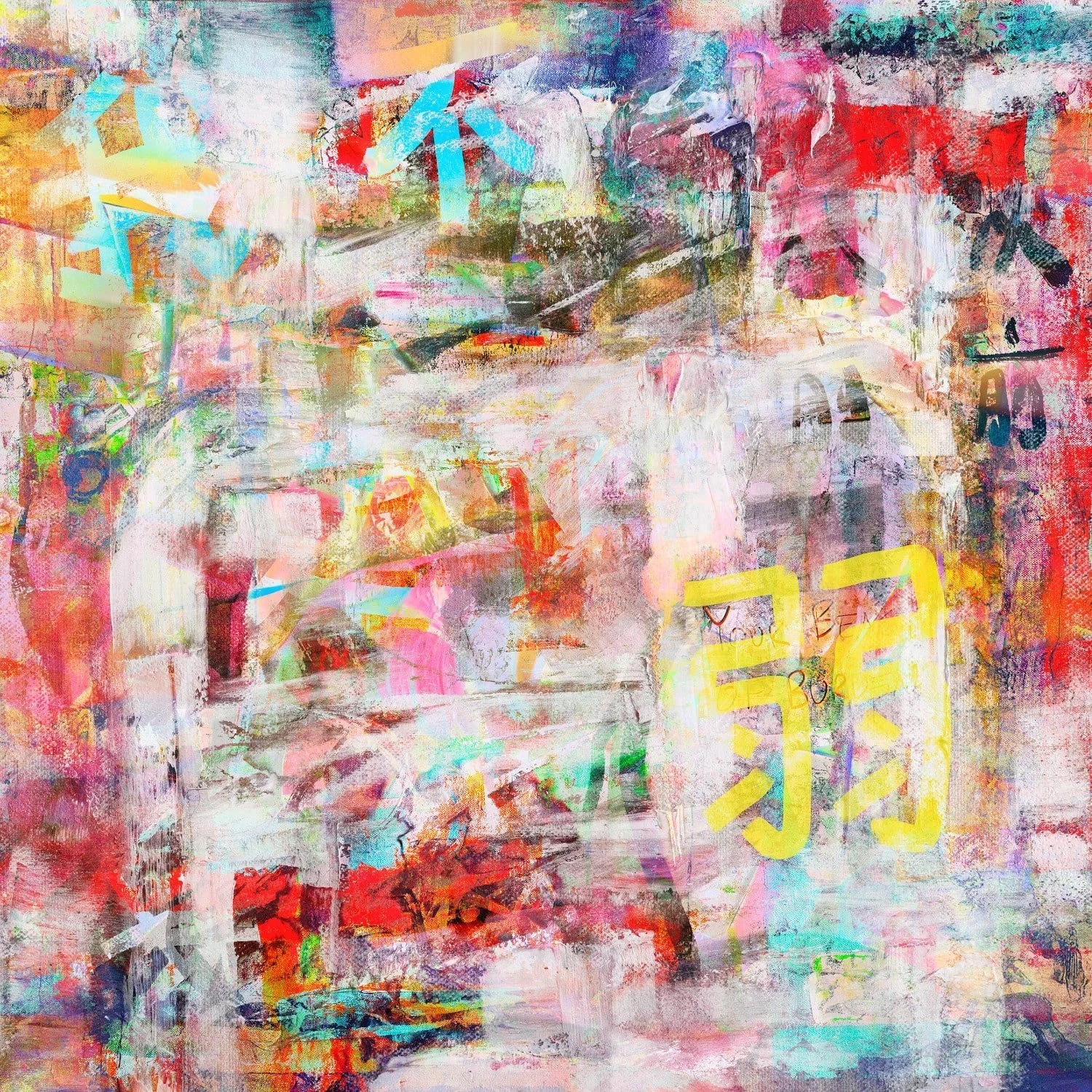

Impression of Samsara #2, Digital painting, 42x30 cm, 2025 © Sapphire (Shiyu) Zhang

INTERVIEW

First of all, tell us a bit about yourself. Who are you, and when did you first realise you wanted to be an artist?

My name is Sapphire Zhang, and my Chinese name is Shiyu Zhang. I am a Chinese female artist and researcher, currently pursuing a PhD in Art and Design. My current research takes an interdisciplinary approach, bridging art, design, and psychology, with a particular focus on art therapy and spatial healing.

My desire to become an artist grew gradually, deeply influenced by my family background. My father is both an architect and an interior designer, and my mother was once a graphic designer and fashion model. Growing up in an environment where visual culture and design thinking were part of daily life, I was constantly surrounded by creative conversations, sketches, and images. It wasn’t so much a sudden decision to “become an artist” as it was a process of absorbing the aesthetics, problem-solving methods, and ways of seeing that art offers. Over time, I began to notice how creativity shapes not only objects and spaces but also emotions and relationships, an observation that continues to guide my practice today.

Impression of Samsara #3, Digital painting, 42x30 cm, 2025 © Sapphire (Shiyu) Zhang

What first inspired you to use collage and abstract painting as part of your artistic practice?

Before beginning my PhD, my professional background was entirely in architecture and interior design. At that stage, art, if I even called it that, functioned for me primarily as a logical or functional solution, a means of resolving spatial or structural problems. I worked far more in design than in what might be considered “pure art.” As a result, I often felt I was not especially skilled at creating something entirely from nothing.

Collage and abstract painting entered my practice as a way of addressing that limitation. Collage, for me, is an act of collecting and recording: fragments I encounter, materials I am drawn to, moments I wish to hold on to. Sometimes these compositions follow a clear logic; other times, they are purely emotional. The content is often deeply personal, yet I choose not to be overly literal partly to protect aspects of my inner world, and partly because ambiguity allows for richer interpretation.

In my current research, collage and abstraction have become more than aesthetic strategies; they are functional tools, much like design. They allow emotions to be visualised and expressed openly, yet with layers of symbolism that can “freeze” a particular state of feeling in time. The same image fragment, placed in a different moment, can take on entirely new meaning; each act of placement becomes a crystallisation of mood.

I am particularly drawn to how collage can be used in therapeutic contexts. During my visits to a women’s mental health hospital, I saw how creative processes, whether colouring, painting, or arranging photographs, could open non-verbal channels of connection, even when spoken language felt inadequate. Collage has no technical barrier to entry, yet it can serve as a subtle way to explore the psyche, both one’s own and that of others. In that sense, it is a practice that bridges rational structure and emotional openness, which is precisely why it continues to anchor my work.

What training or experiences helped you become the artist you are today?

My educational journey began in China, where I completed a four-year undergraduate degree that focused heavily on the fundamentals of drawing, colour theory, aesthetics, and the practical skills required in design. This period also included internships and work experience in a design institute, where I developed a pragmatic, problem-solving approach grounded in the realities of architectural and interior design.

My time at the University of the Arts London opened a different kind of space in my thinking. There, I was encouraged to question assumptions, to embrace conceptual risk, and to recognise that a project’s value did not always depend on its immediate functionality. This expansion of perspective prepared me to move beyond purely design-oriented outcomes.

The turning point came before I began my PhD, when I had increasing contact with mental health communities and began reflecting more deeply on my own psychological state, as well as on women’s mental health more broadly. These encounters shifted my priorities and led me to transition from design toward projects rooted in art therapy and spatial healing.

Moving between China and the UK has further enriched my understanding of how culture shapes our relationship to the body, space, and emotion. Experiencing these differences has influenced the way I approach audience interaction in my work, allowing me to design experiences that respond to both personal and cultural layers of meaning.

Impression of Samsara #1, Digital painting, 42x30 cm, 2025 © Sapphire (Shiyu) Zhang

Impression of Samsara #5, Digital painting, 42x30 cm, 2025 © Sapphire (Shiyu) Zhang

In your work, you layer fragmented memories and body images. Can you share how you choose these elements?

When collage or abstract art becomes a process of self-expression rather than a tool for art therapy, I approach it entirely from a self-centred perspective, not in the sense of exclusion, but in the sense that every element must have a personal connection. These may be things I have seen, sensations I have felt, or fragments I have recorded almost unconsciously. In the moment I place them on the canvas, they carry a specific meaning, even if that meaning is difficult to articulate.

For me, the body is a tool for recognising the self through its form, its movement, and even its tactile sensations. In collage, I am interested in expressing multiple perspectives on the body, particularly within different cultural contexts. In China, for example, the exposure or display of the body, especially the female body, often encounters greater resistance. Across cultures, many women live within a similar set of constraints, shaped by societal ideals and expectations that may not align with their own preferences. This does not make those ideals inherently wrong, but they are not always self-chosen.

My artistic process often begins with recognising myself and presenting my own interpretations of other symbolic imagery. These choices usually reflect whatever questions or tensions I am working through at the time. By combining collage and abstraction, I can bring together what might seem like unrelated or meaningless fragments and arrange them as a way of clarifying my own thoughts. The act of placing them on the canvas creates a certain distance, allowing me to see myself from another angle while feeling a deeper connection to my own emotions. Ultimately, layering fragmented memories with body imagery becomes a form of self-exploration, an inquiry into what my body and these emotional fragments mean to me at this moment in time.

Your series Sapphire in White reflects on the image of oneself in a wedding dress. What does this symbol mean to you?

I see the wedding dress as more than a garment; it is a symbol, a stage, and often, a fantasy. At one point, I began to think of it almost as a trap, an illusion carefully packaged to appear perfect. Many women grow up imagining the wedding they will have or picturing themselves in a dress that represents the ideal marriage or the idealised form of love. Yet, in that idealisation, the harsher realities of marriage are often overlooked. Beneath the polished surface of the dress, no one can truly see the emotional dynamics or struggles that may exist within the relationship. In this sense, the wedding dress can conceal truths that women must eventually confront, presenting marriage as something sacred and flawless while quietly leading them into what I see as a kind of societal snare.

At the same time, the wedding dress plays an undeniable role in the shifting of a woman’s social identity. Wearing it or even engaging with its symbolism marks a transformation from being an independent individual to being perceived, socially and culturally, as part of a family unit. For some, this may fulfil a personal desire or reinforce a sense of self-worth; for others, it may feel like the imposition of external expectations.

The wedding dress is therefore both an aspiration and a constraint. It embodies beauty and hope, yet also encodes the invisible structures that shape women’s lives. This tension is precisely why I consider it a rich subject for artistic exploration, a site where personal dreams, cultural narratives, and the complexities of identity intersect.

Impression of Samsara #4, Digital painting, 42x30 cm, 2025 © Sapphire (Shiyu) Zhang

In your work, you use nude self-portraiture to challenge beauty standards. How has this process impacted your own self-image?

For me, working with nude self-portraiture is both an expression of self-identification and a declaration of bodily autonomy. In many societies, the female body is held to a set of standards that are not only arbitrary but often at odds with natural diversity. These standards go beyond size or weight; they extend into minute, highly specific expectations about body hair, breast shape, the appearance of the genitals, and countless other details.

Much of this scrutiny is rooted in a male-oriented visual framework, where the female body is subjected to an externalised standard of approval. Yet when women look at themselves or at each other, the perception is often very different, more nuanced, more aware of the lived realities of the body, and less bound by the stigmas that have been culturally attached to certain physical traits.

Through my work, I am less interested in conforming to a “social standard” than in dismantling its authority by showing myself without apology. I see the physical form, the “skin” we inhabit, as only a small fragment of identity, and an even smaller fragment of self-expression. If I, as an artist, am unwilling to present this part of myself without fear, then the range of what I can express becomes severely limited. Nude self-portraiture, in this sense, is not simply an image of the body; it is an act of reclaiming authorship over how that body is seen and understood.

How does your work challenge or reframe the influence of the male gaze?

I find the concept of perspective deeply fascinating, particularly in how men and women tend to approach the body, both their own and that of the other, differently. Of course, I cannot speak for everyone, but in my observation, these differences are especially pronounced when it comes to gender-specific features. Many women, for instance, feel a sense of hesitation or even anxiety about revealing certain parts of their bodies. I see this not as a weakness, but as a protective instinct, a way of safeguarding one’s physical self.

Men, on the other hand, often appear more accepting of their own bodies, yet their approach to the female body can involve a kind of visual inspection, even if not overtly objectifying. There is a subtle but persistent tendency to evaluate whether a woman’s physical features meet certain standards. This evaluative gaze, in my view, borders on a visual form of intrusion, an uninvited assessment that is rarely mirrored in how women regard male bodies.

My work aims to disrupt that imbalance. I want the act of looking at my pieces to be decoupled from male authority, to remove the implicit assumption that my body is subject to someone else’s judgment. The images I create are not seeking validation; they are assertions of self-possession, demonstrations of my own agency over how my body is presented.

Yet, I also feel a certain sadness in acknowledging that women must sometimes resort to such artistic strategies simply to claim their rights, to insist on their presence. The very fact that the term “male gaze” exists signals, to some extent, the persistent marginalisation of female subjectivity. In that sense, my work is both a personal declaration and a critique of the conditions that make such declarations necessary.

Mirror Without Permission, Digital painting, 95x40 cm, 2025 © Sapphire (Shiyu) Zhang

Sapphire in White, Digital painting, 57x30 cm, 2025 © Sapphire (Shiyu) Zhang

How do you see art functioning as a tool for personal and collective healing?

For me, collage and abstract art are fundamentally processes of self-organisation. Every element I use comes from somewhere: photographs I have taken, images I have recorded, fragments from daily life. When I search for these materials, whether flipping through an old album or revisiting casual records of my surroundings, I am already reconstructing those moments in my mind. The act of selecting and arranging them becomes a form of self-healing.

Encountering certain images again can trigger a tangle of emotions, memories, reflections, and an urge to express. Some photographs lose their emotional weight over time, quietly fading from the foreground of memory. Others retain their intensity, helping me recognise which feelings truly matter to me. In cutting and reassembling these emotional fragments into something artistic, I often find the process deeply relieving, even cathartic. At times, working through difficult emotions can be intense, but once processed, it becomes an opportunity for self-reflection, self-recognition, and a kind of internal dialogue.

In my research, I also use collage as a tool to study what others are expressing through their own arrangements of imagery. Beyond personal expression, collage can serve as a collective healing process, helping non-specialist participants communicate emotions that are difficult to articulate verbally. For an artist, the practice may involve certain aesthetic considerations, but for someone outside the art world, it can be a purely functional medium, one of communication, restoration, and connection. Collage and abstraction are thus both functional and aesthetic, their role shifting according to the audience and the intention behind the work.

Do you see your art as more personal or universal, or a mix of both?

I believe that art is always grounded in the personal. It begins as a self-driven process, a means of expressing what is often incommunicable in other forms. This is especially true for collage and abstraction, where the layers of meaning can be highly private, metaphors that only I, as the artist, fully understand. A viewer may see the work without grasping its specific references, because those references are tied to my own experiences and memories.

At the same time, there are elements within the work that can operate beyond the personal. Even with the cultural barriers and differences in context between audiences from different backgrounds, and the technical barriers between artist and non-artist, certain visual elements retain a shared resonance. Colour relationships, recurring motifs, and certain image-based metaphors can function as what I would call universal symbols, speaking across linguistic and cultural boundaries.

So while my practice is predominantly personal in origin, it also has a partial universality. These shared symbols and sensory cues allow the work to serve as a channel for collective communication, creating spaces where individual narratives and common human experiences can intersect.

Impression of Samsara #7, Digital painting, 42x30 cm, 2025 © Sapphire (Shiyu) Zhang

Lastly, what are you currently exploring in your studio practice? And what can we expect next?

At present, alongside my more introspective, long-form emotional work, I am increasingly drawn to exploring immediacy in my practice. By this, I mean creating works that respond directly to the present moment places I visit, landscapes I encounter, sensations that arise in real time. These are not entirely disconnected from emotion, but they focus on recording and translating the immediacy of an experience rather than revisiting it through layers of memory or philosophical reflection.

Collage and abstraction lend themselves particularly well to this approach. Unlike more traditional forms of painting that require extended preparation, these methods allow for a rapid transformation of perception into visual form. I want to harness that immediacy not as a substitute for deeper, cumulative work, but as a complementary mode that captures the rawness and spontaneity of lived experience.

Looking ahead, I plan to develop a series of works and studies that explore this responsive process, using the speed and adaptability of collage and abstraction to document shifting environments and emotional states as they happen. The aim is to expand my research beyond the slow accumulation of meaning, into a space where art operates as a direct, unfiltered dialogue with the present.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.