10 Questions with Bogdan Kanuka

Bogdan Kanuka is a multidisciplinary artist working with printmaking, painting, and sculpture. He focuses on linocut and monotype, using these techniques to explore how repetition, variation, and gesture can tell open-ended stories. His prints often include symbolic animals or invented figures that suggest inner states, memory, and change.

Originally from St. Petersburg, Russia, Bogdan studied art and design in Moscow at the British Higher School of Art and Design, the HSE Art and Design School, and the Free Workshops at MMOMA. He is currently developing Kanuka Studios, a platform-in-progress focused on contemporary printmaking and cross-disciplinary exploration.

He is currently based in New York on an extended research visit, developing new work that connects visual traditions across cultures. His recent series combines expressive mark-making with clear structure, showing how printmaking can be both methodical and emotional. His work has been shown in exhibitions in Moscow and is now entering international platforms.

Bogdan Kanuka - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Bogdan Kanuka is an artist who works between printmaking, painting, and sculpture. His main focus is linocut — a traditional printmaking technique — which he transforms through monotype methods, making each print in the series slightly different. This mix of control and spontaneity allows him to explore ideas of change, rhythm, and presence.

Many of his works feature animals or symbolic figures, often invented or dreamlike. These characters speak about memory, transformation, and how we shape — or are shaped by — the world around us. For Kanuka, they are not just images but parts of a larger story that continues across prints, objects, and time.

Alongside printmaking, he creates ceramic sculptures that grow out of his graphic work. Clay allows him to think in space — to translate his sketches and forms into something physical and raw. His pieces are intentionally textured and expressive, resisting perfection in favour of feeling.

Kanuka sees art as a place of attention — a quiet focus on what is usually hidden. Through repeated forms and open-ended symbols, he invites the viewer to slow down and connect with something deeper.

Tree of life, Linocut Monotype, 61x86 mm, 2024 © Bogdan Kanuka

INTERVIEW

First of all, can you tell us a bit about your background and how you first became interested in art?

I’ve always been drawn to visual culture — ballet, theatre, fashion, and photography. I explored many forms: I worked as a designer and a photographer and studied scenography and fashion. But gradually, I realized that drawing absorbed me more than anything else — that state where you’re alone with the image and everything else disappears.

Through drawing, I arrived at printmaking and sculpture. I became fascinated by how a single idea could evolve as it passed through different mediums — linocut, ceramics, and painting. It felt like each material opened a new dimension as if a project was growing its own body. That hunger for transformation became the core of my method.

What did you take away from your studies at BHSAD and the HSE Art and Design School?

When I get deeply involved in something, I enter a kind of greedy state — in the best sense: the desire to understand, to try everything, to miss nothing. I initially planned to study contemporary art, but I quickly realized that I needed to build a visual language first. That’s why I chose illustration — a discipline where you think visually, generate ideas quickly, and solve problems through experimentation.

The program at BHSAD was extremely rich: painting, printmaking, silkscreen, ceramics, animation, 3D, artist books, andmurals. Illustration there covered the entire spectrum of art. At the same time, I was studying at HSE — one program in the morning, the other in the evening. Sometimes, the themes overlapped, which only intensified the effect: I started running a single idea through different forms — drawing, printmaking, and sculpture. This approach stayed with me: not choosing the medium in advance but letting the idea find its form through multiple languages.

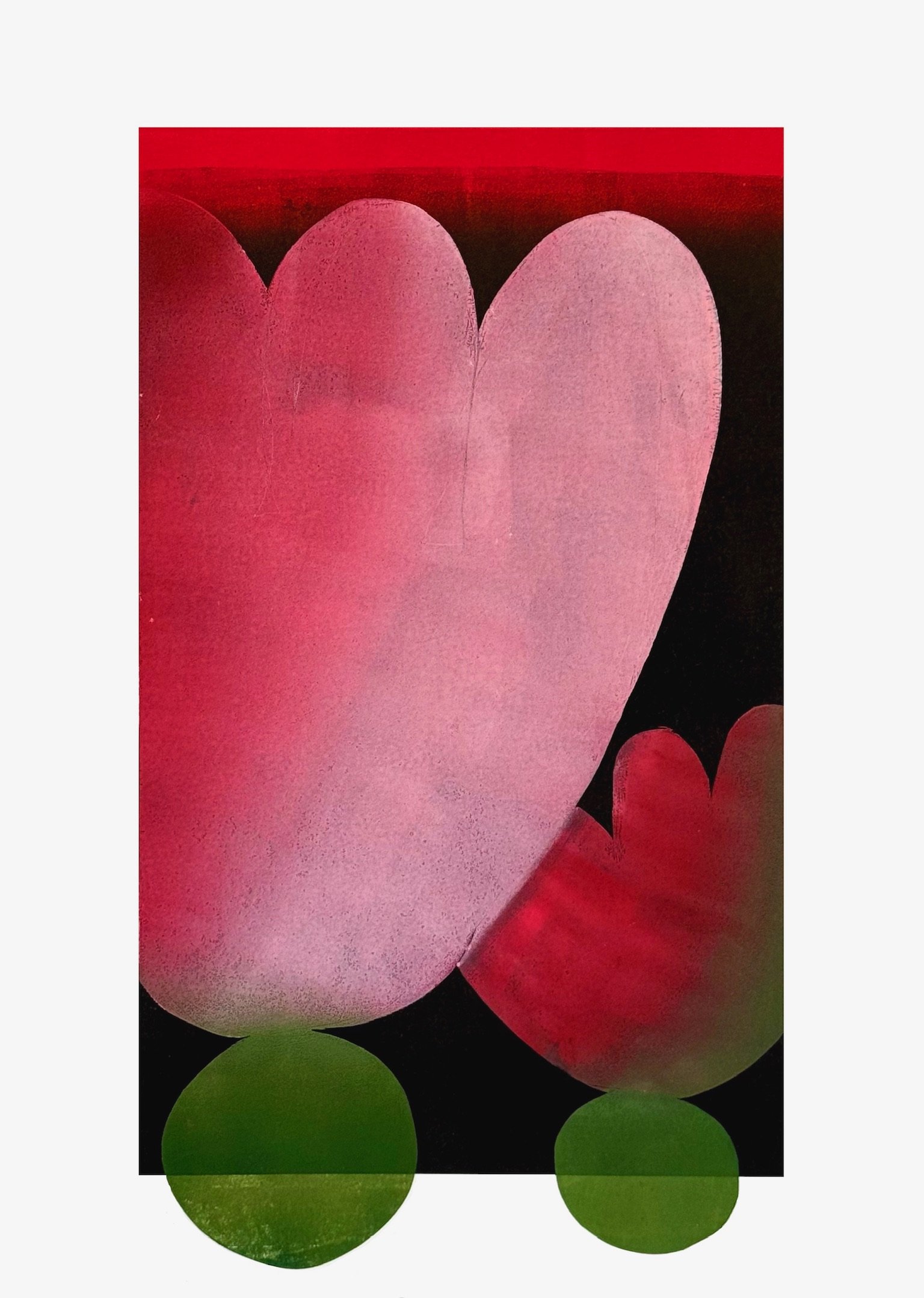

Blooming, Linocut Monotype, 61×43 mm, 2024 © Bogdan Kanuka

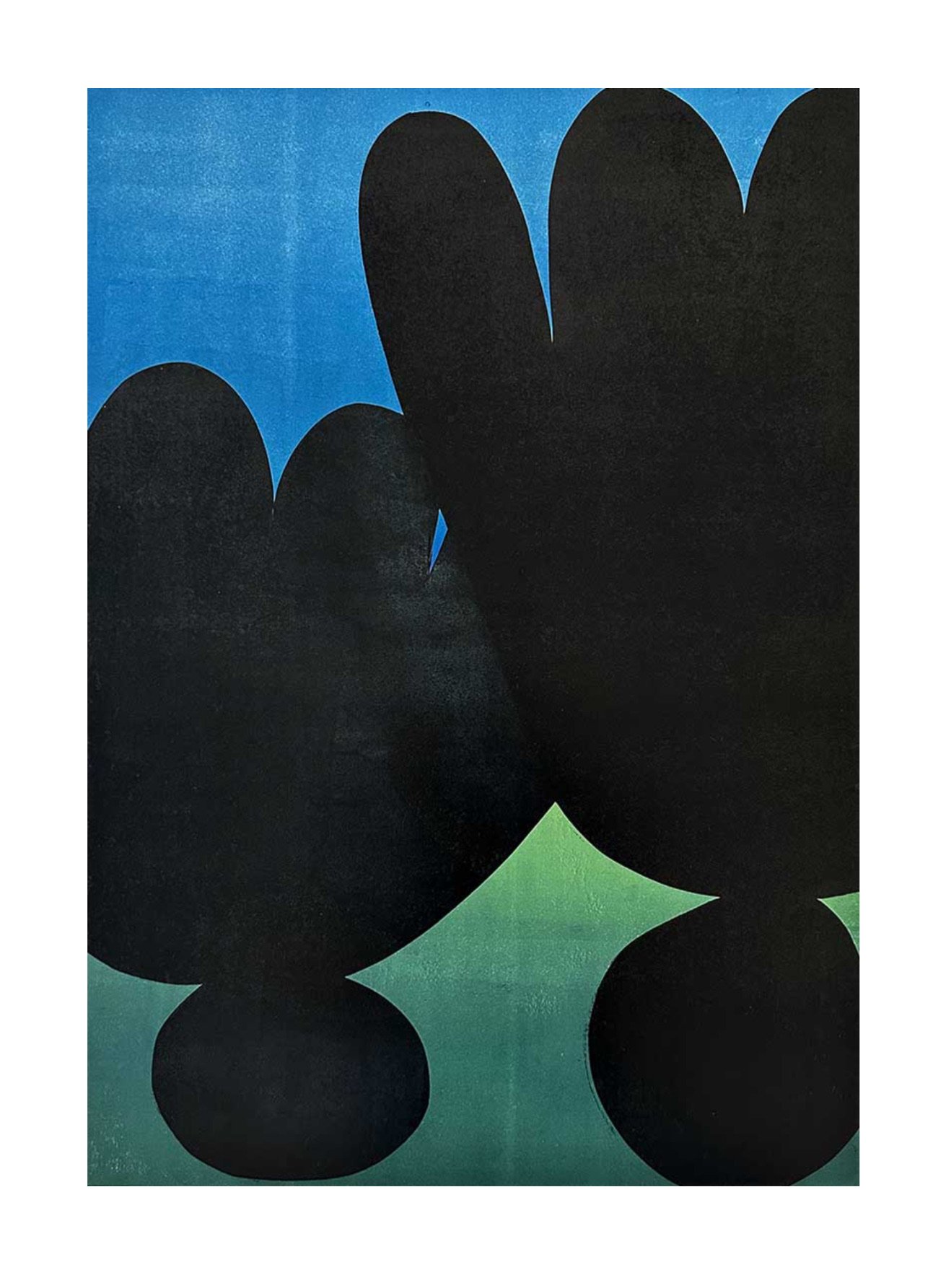

Bushes, Linocut Monotype, 61x86 mm, 2024 © Bogdan Kanuka

Why did you choose printmaking — especially linocut and monotype — as your primary focus?

For me, printmaking is always an experiment. I never know exactly how the result will look — and that’s the most exciting part. Over time, I’ve learned how to control parts of the process, but every print still contains an element of surprise — sometimes even magic.

My technique is a personal reinterpretation — something between linocut and monotype. I build layers more like a painting than a traditional relief print. Often, I start with gradients or soft backgrounds, then add shapes without carving outlines — just solid fields of colour. I like to blend colors within a shape using a roller, so the surface breathes and vibrates. It’s intuitive, physical, and a bit alchemical.

I rarely work with sketches. I prefer to cut directly — creating simple, awkward, even “dumb” shapes. But in their clumsiness, they become alive, funny, and touching. These are not things I would draw intentionally. They come from the material, from play. And every time I lift the paper after printing, I feel a kind of joy — even surprise. I often think, “Wow — I wouldn’t have come up with this on purpose.”

How do you balance structure and spontaneity in your process?

I usually begin with a plan: background, layers, figures. Sometimes, I make a sketch to set the direction — but in the process, it often changes. The sketch gets deformed or disappears entirely. I trust my intuition: if something feels missing, I immediately cut a new shape and print it in.

Because I work in printmaking, each impression is a little different. I create small editions and often vary the pressure or pigment. Sometimes, I don’t re-ink a form and print the “ghost” — a faded trace that can be more expressive than the original. Sometimes it works. Sometimes, it doesn’t — and I either add a new layer or draw directly on top.

I also like changing the colors from print to print, or rearranging shapes in the final layer. When there are multiple elements, the composition can drift. That’s what makes the process feel alive. There’s a structure — but always space for accident, mistake, correction.

It’s like directing with room for improvisation. And sometimes, the final gesture is drawing by hand — one last final touch before it comes alive.

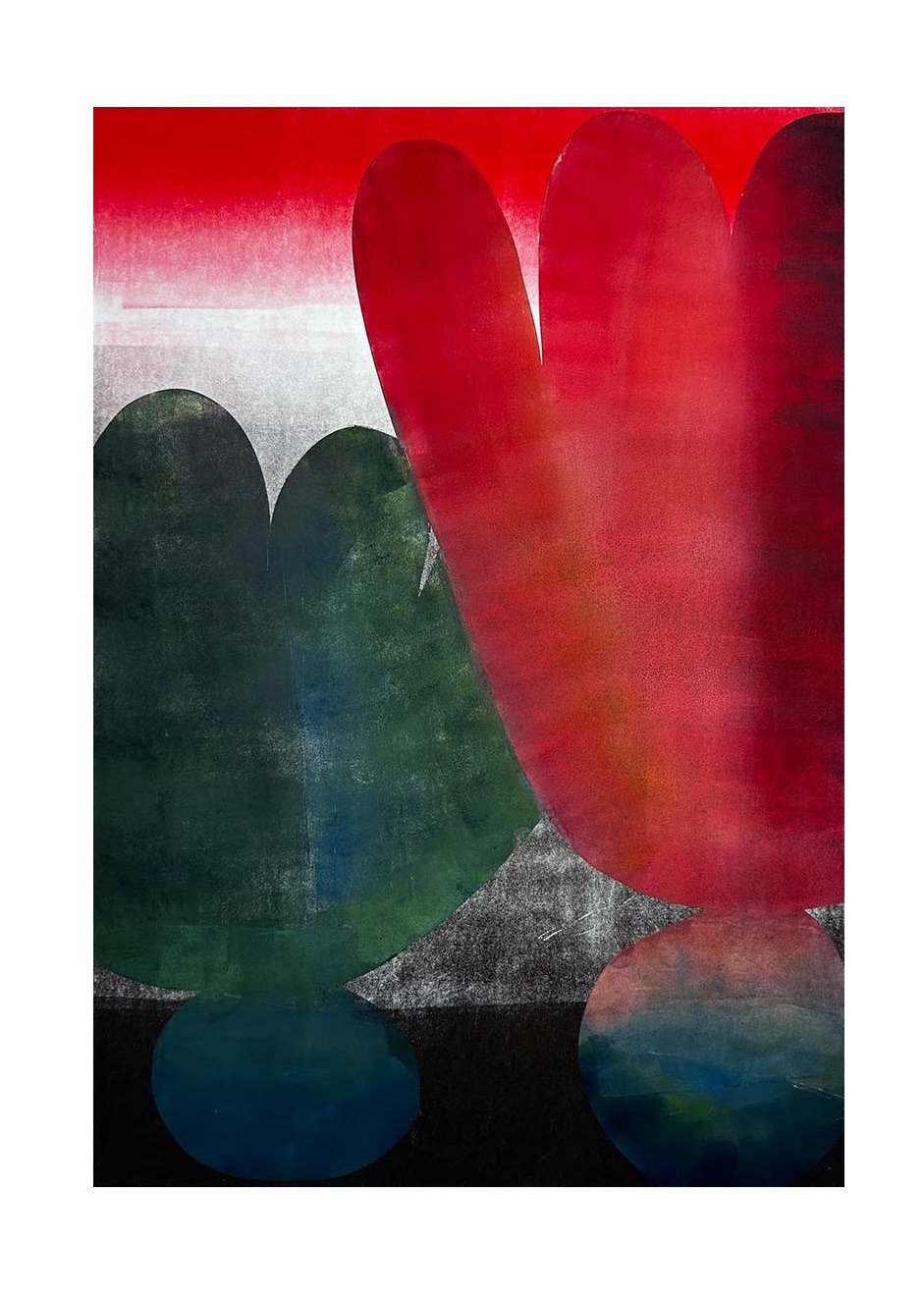

Rain God, Linocut Monotype, 61x86 mm, 2024 © Bogdan Kanuka

Your work often features symbolic animals and invented figures. Where do these characters come from?

They come from experimentation. In both linocut and ceramics, I search for expressive forms — and they often appear by accident. In one recent series, I ended up with a bird-elephant and a dog-elephant, even though I honestly tried to make just an elephant. But the “correct” version was boring. The hybrid felt strange, touching, and alive.

Whenever I try to draw people in an academic way, I lose interest quickly. There’s something dull about correctness. Strange, dumb-looking creatures — they’re fun and full of energy. That’s how I arrived at my diploma project, “Africa,” and over time, animals became part of my language and method.

I don’t see them as characters, really — more like emotional forms. They’re a kind of visual alphabet, readable without translation, not about realism, but about inner states.

How does your sculpture relate to your paper works?

For me, sculpture is a way to animate the print — to give it a body. Sometimes, I look at an image and wonder: what if it stood up, became an object, or took up space? That curiosity pulls me further. It began during my illustration studies, where we were encouraged to shift between media — to sculpt first, then draw, then transform again. That rhythm stayed with me.

I don’t divide print and sculpture — they feel like two breaths of the same thing. My ceramic figures often originate from linocut characters, but once in three dimensions, they mutate — proportions shift, and new ideas appear. Sometimes, it’s the opposite: sculpture comes first, and then the prints follow.

To be honest — I still can’t choose. I love both. In my case, they depend on each other. It’s like a conversation: first, you speak, then you listen. But the response comes in a different language.

What does repetition mean to you as a method?

Repetition isn’t always inspiring. Sometimes it’s boring. But it’s part of the discipline — a rhythm, a structure, a way to keep going. And within repetition, I create small deviations. I don’t like making exact copies. Even within a print edition, I want each piece to feel unique.

I allow myself to play: I’ll change the colour, remove a detail, or add something small. Sometimes, I hide little Easter eggs — differences you only see if you really look. Not because I have to, but because otherwise I’d lose interest.

Repetition, for me, is not duplication — it’s a space where transformation happens. The new idea isn’t always in the first attempt. Sometimes, it only appears the sixth or seventh time.

Football, Linocut Monotype, 61x86 mm, 2024 © Bogdan Kanuka

Сrocodile, Linocut Monotype, 61x86 mm, 2024 © Bogdan Kanuka

Storm, Linocut Monotype, 61x86 mm, 2024 © Bogdan Kanuka

Stolen sun, Linocut Monotype, 61x86 mm, 2024 © Bogdan Kanuka

You’ve mentioned an interest in open-ended storytelling. How do you want viewers to engage with your work?

I aim to create an emotional atmosphere — something kind, slightly sad, or humorous. I don’t construct a single storyline. I create an image that’s open — and people read it in their own way.

Maybe it connects to my childhood — Soviet cartoons, humour magazines, and strange animal shows on TV. There was a kind of innocence in them, but also sharp emotional clarity. My work is often described as “touching,” and I take that as a compliment. I don’t explain what people are supposed to see. I want the viewer to bring their own memory and their ownfeelings into it.

Tell us about Kanuka Studios. What are your goals for this platform?

Kanuka Studios started as a personal space to publish my own works — prints, artist books, and ceramic multiples.However, I see it evolving into a broader platform for curating, collaboration, and independent publishing.

I’m drawn to zine culture and tactile formats. I’m working on unconventional children’s books — ones with colouring elements, embedded stories, and maybe even an app where kids can draw inside the world. I want to build a small art publishing space that’s playful, visual, and experimental.

For me, Kanuka Studios is a bridge between intuition and structure — between the studio and the world outside.

Cloudy, Linocut Monotype, 61×42 mm, 2024 © Bogdan Kanuka

What are you currently working on in New York, and what’s next?

Right now, I’m working on a series called “Toys.” It includes printmaking, painting, and ceramics — all based on the idea of rocking bases, like old-fashioned toys that swing back and forth like a pendulum. Traditionally, it’s a rocking horse. In my case, it’s a sun, a plant, or a bird-elephant hybrid.

I’m interested in exploring the feeling of instability — of movement and imbalance — as a visual metaphor for childhood, memory, and inner shifts. It’s a theme that feels both light and slightly unsettling, and in material form, it becomes especially precise.

The series moves across multiple mediums: I’m also preparing a book where these images will continue evolving. Right now, I’m collecting material, testing visual connections, and thinking about how to bring these layers together into one complete object or edition.

At the same time, I’m continuing to develop Kanuka Studios as a space for artistic production, independent publishing, and visual experiments.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.