10 Questions with Ming Cheng

Ming Cheng is a New York–based graphic designer whose work moves between visual design, theatre, and emotional storytelling. As a designer originally from China, she explores the relationship between form, language, and human experience.

Her professional background includes working with The New York Times, American Ballet Theatre, and the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, where she developed visual systems and campaigns that bring together clarity and rhythm. Ming’s work has been recognised internationally, including her achievements in the New York Product Design Award and the Indigo Design Award, which highlight emerging voices in global contemporary art and design.

Ming Cheng - Portrait

ARTIST STATEMENT

Ming Cheng’s practice explores how design can express the subtle distance between people and the spaces they inhabit. Her work reflects on belonging, intimacy, and the subtle emotions that shape modern life.

Often beginning with observation, she collects fragments from daily encounters, theatre, and literature, transforming them into visual narratives through typography, layout, and material. Each project becomes a way to translate inner emotion into visible form, turning silence and uncertainty into something tangible.

In her recent work, Ming continues to explore design as a poetic language. She focuses on sincerity, patience, and presence as a way to create meaning in an overstimulated world.

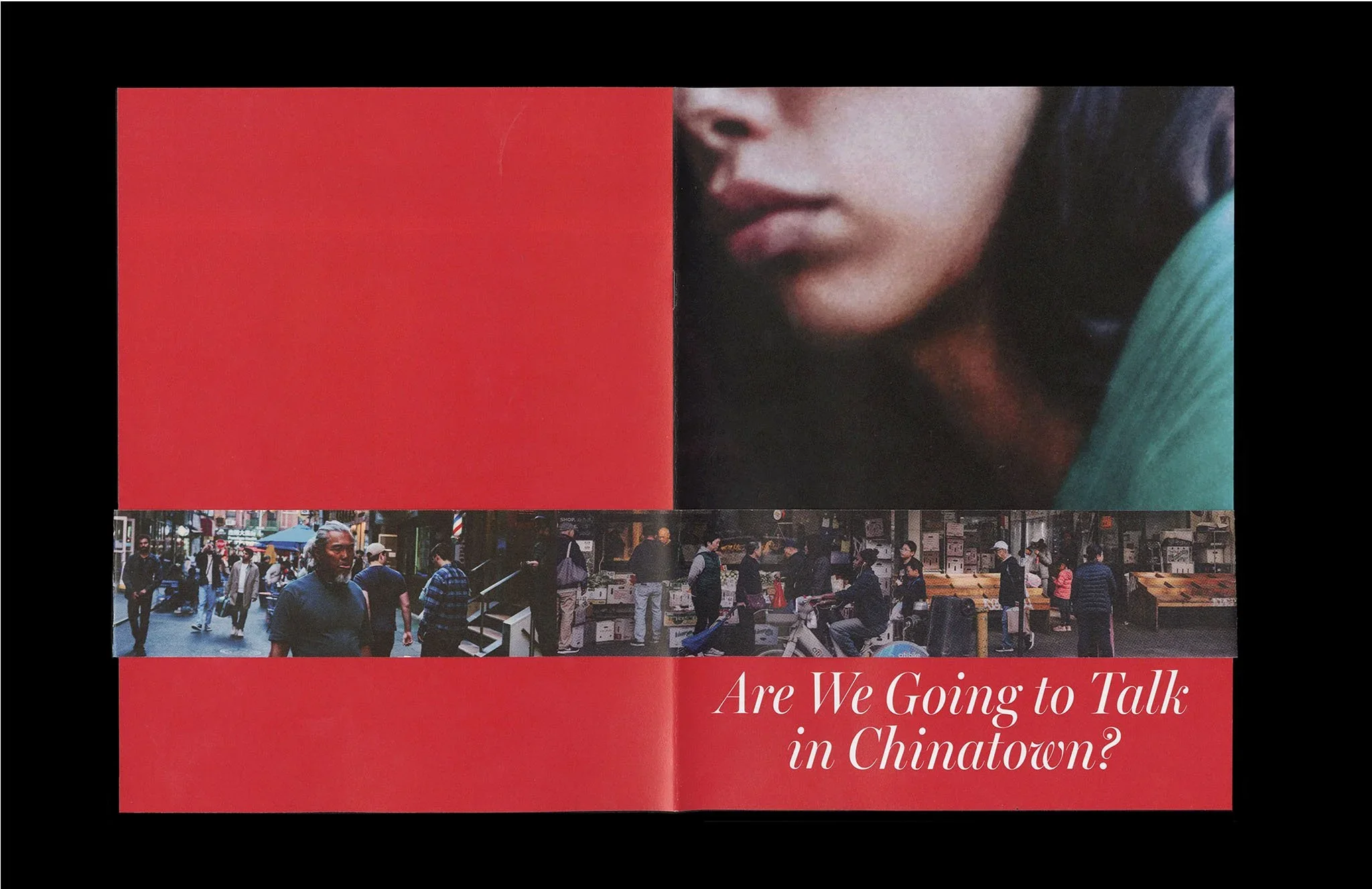

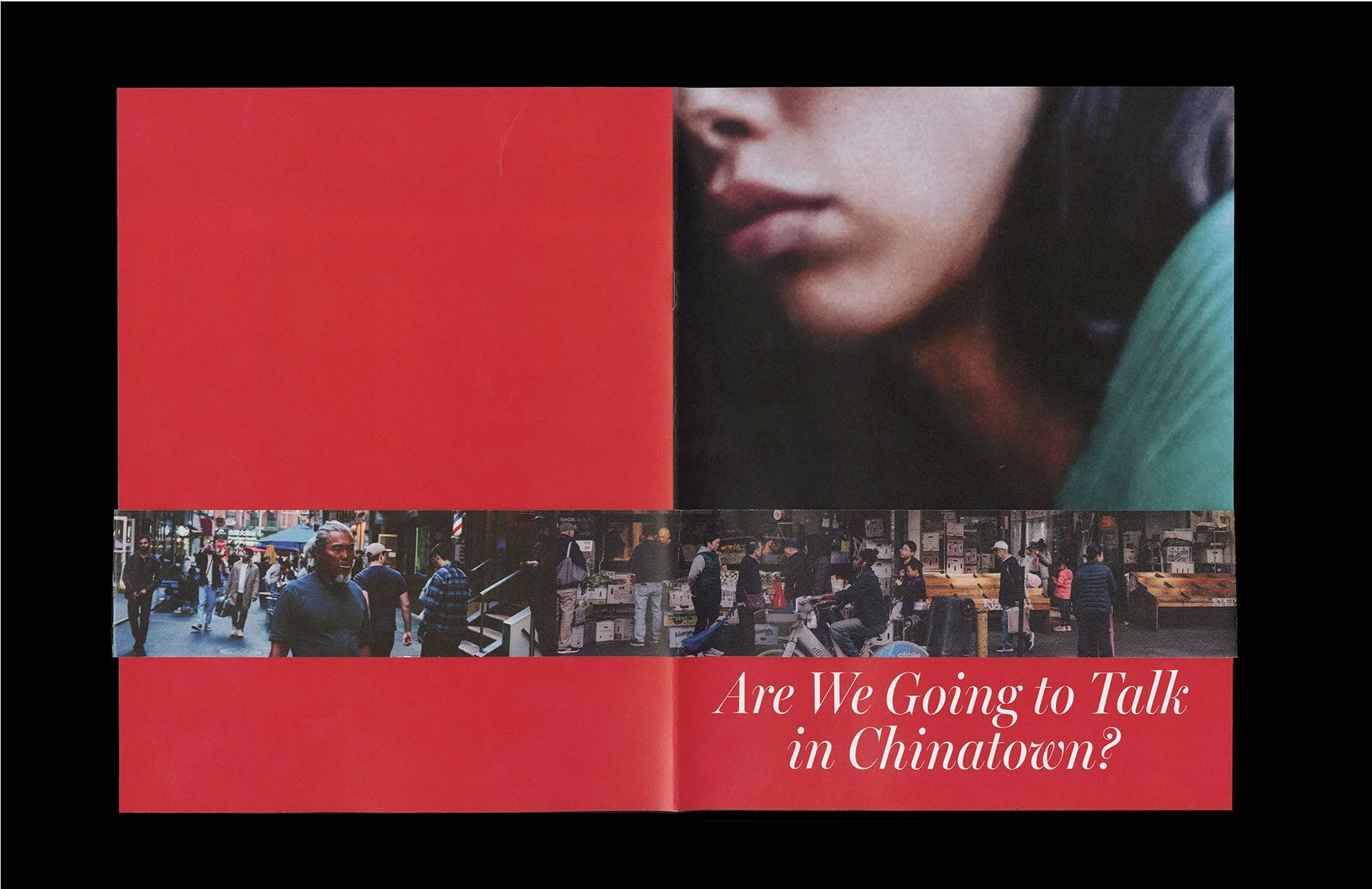

Are We Going to Talk In Chinatown, Print, 8.6x11.2 in, 2025 © Ming Cheng

INTERVIEW

First of all, can you tell us about your journey from China to New York and how this move has influenced your perspective as a designer?

I grew up in Nanchang, China, where people rarely speak their feelings directly, and a lot is understood through pauses and atmosphere. That taught me to notice emotional subtleties, which became important in how I look at images and communicate through design. Moving to New York changed the way I express myself, because here people speak with more directness and confidence, and I had to articulate my ideas clearly. The distance between these two ways of being gave me a dual perspective. In China, I already knew how to observe, and in New York, I started to focus on projecting. Now my work sits in the space between those modes, finding ways for information to be communicated clearly. The move did not replace one identity with another. It simply added another layer.

How did you first become interested in design, and what drew you to the intersection of visual design and storytelling?

I came to design gradually. When I was younger, I spent a lot of time in bookstores and cinemas, noticing how visuals shape mood and how that mood stays with you afterwards. Later, when I began my journey of visual design, I realised that images can carry feeling in the same way. A typeface or layout can set a tone before any words are read. That connection between visual choices and the inner response they create is what drew me to the intersection of design and storytelling. I am interested in the moment when someone encounters a piece of work and feels something instinctively, before they analyse it.

Your work often connects design with emotion. How do you approach translating feelings like belonging or intimacy into visual form?

For me, emotion is not something I try to illustrate directly. I usually start by thinking about the conditions around the feeling. For example, belonging can feel like softness, familiarity, or a steady rhythm. I look for materials, colours, pacing, or spatial relationships that can create that atmosphere. I try to design the environment in which the emotion can be felt, rather than designing the emotion itself. It is less about showing and more about allowing. And even though my work carries personal traces, it is shaped through careful visual decisions rather than simply expressing emotion for its own sake.

Are We Going to Talk In Chinatown, Print, 8.6x11.2 in, 2025 © Ming Cheng

What inspires you most in your daily life or surroundings when starting a new project?

I get a lot of inspiration from theatre. As a New Yorker, I go to Broadway and smaller experimental performances often.Sitting in a room with actors feels very intimate. I can feel the space become charged by movement, silence, breath, and the audience’s attention. It reminds me that storytelling is not only about narrative, but about how something is felt in that specific moment. Watching new work from playwrights who are pushing form and edgy ideas also gives me a sense of what is possible. When I start a new design project, I think about how to create that same kind of presence, where the viewer feels closely engaged even without being told what to feel.

You’ve collaborated with major institutions like The New York Times and American Ballet Theatre. What have these experiences taught you about visual communication?

Working with these institutions taught me that visual communication is as much about clarity as it is about character. Both The New York Times and American Ballet Theatre have deeply established voices, so the work needs to support that identity rather than compete with it. At The New York Times, I worked on motion visuals for the Family Subscription campaign during a period of significant digital audience growth. In 2022, the Times recorded its largest net increase of digital subscribers, approximately 460,000, since it began reporting subscribers across products. Contributing to a campaign that reached audiences during that moment made me more aware of how visual decisions shape perception. Tone, hierarchy, and pacing influence whether information feels accessible, warm, or distant. It perfectly showcases that clarity itself can create trust. At American Ballet Theatre, the context was different. The work needed to honour the institution’s history while speaking to contemporary audiences. I paid attention to subtle shifts in color, rhythm, and movement to create a sense of presence rather than spectacle. Across both experiences, I felt that design can carry personal sensibility even when it must remain precise and functional. The responsibility of the designer is to understand when to step forward and when to hold back, so that expression and purpose remain in balance.

How do theatre and literature influence your visual language and design sensibility?

Theatre and literature influence the way I think about structure and pacing. When I read or watch a performance, I enjoy seeing how tension builds, how blank space works, and how something unfolds over time. That affects how I design a page, a poster, or a motion piece. I think about when to hold back and when to reveal, how to let the viewer arrive at the meaning on their own, and how images and text can breathe together. It is less about illustrating a story and more about carrying the feeling of time and movement into visual form.

Are We Going to Talk In Chinatown, Print, 8.6x11.2 in, 2025 © Ming Cheng

Are We Going to Talk In Chinatown, Print, 8.6x11.2 in, 2025 © Ming Cheng

Can you describe your creative process, from collecting fragments of inspiration to completing a finished design?

My process usually begins with collecting small fragments. I take notes from a novel, photos from a grocery store, and everything on the chaotic city’s streets that catches my attention. Then I sit with them for a while and look for a shared tone or direction. Only after that do I start sketching or building a visual structure. I try different compositions and type treatments, then I step back and edit. The work becomes clearer through removing rather than adding. The finished design still carries the traces of where it began, but it has its own shape and space to stand on its own.

What does “design as a poetic language” mean to you in practice?

When I say design can be a poetic language, I mean that visuals can communicate in a way that is felt before it is explained. Poetry often works through the interesting relationships between non-related things rather than direct description with tons of details like an explanatory dictionary. I think design can do the same. In practice, I try to create a visual space where the viewer can enter and form their own connection with a freedom and imagination space, instead ofbeing told what to think. It is not about being mysterious. It is about leaving room for feeling and interpretation to happen naturally.

Are We Going to Talk In Chinatown, Print, 8.6x11.2 in, 2025 © Ming Cheng

How do you hope people feel or reflect when they encounter your work?

I don’t hope for one specific reaction, because I think everyone brings their own history to what they see. What I hope for is a moment of rethink. A small shift of attention, where someone feels slightly more aware of themselves or their surroundings. If the work can open a quiet space for reflection, or allow someone to recognise a feeling they didn’t have words for yet, that is meaningful to me. I care about creating room rather than directing emotion. The most satisfying responses are the ones where people tell me what they saw in the work, not what I intended.

Lastly, what projects or ideas are you currently developing, and what directions would you like to explore next?

Recently, I’ve been developing the brand identity for a regional theatre company in New York City whose mission I find deeply compelling: to imagine theatre as a shared and communal experience that is accessible, porous, and genuinely open to all. The openness of their vision invites a quiet kind of experimentation, exploring how typography, colour, and rhythm can create an atmosphere that welcomes rather than intimidates, that suggests belonging rather than exclusion. This project has reminded me that design is not only something we look at, but something we enter. It shapes the emotional threshold of a space and influences who feels permitted to step inside, and who feels recognised once they do. Moving forward, I hope to continue working in contexts where culture and community are intertwined, where design can serve as a facilitator of connection and help create the conditions for people to gather and feel part of something shared.

Artist’s Talk

Al-Tiba9 Interviews is a promotional platform for artists to articulate their vision and engage them with our diverse readership through a published art dialogue. The artists are interviewed by Mohamed Benhadj, the founder & curator of Al-Tiba9, to highlight their artistic careers and introduce them to the international contemporary art scene across our vast network of museums, galleries, art professionals, art dealers, collectors, and art lovers across the globe.